IS online: Can it be stopped?

- Published

How is Islamic State run?

A Europe-wide police team is being formed to track and block social media accounts linked to Islamic State (IS).

They aim to get new accounts closed down within two hours of them being set up. Rob Wainwright, Europol's director, told the BBC that the new team, which starts its work on 1 July, "would be an effective way of combating the problem".

What's the scale of the self-styled Islamic State's presence online?

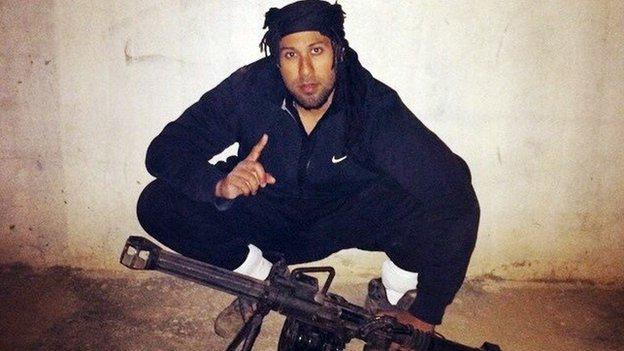

Briton Imran Khawaja, now jailed, took part in online propaganda strategy for extremists

The self-styled Islamic State's propaganda machine is always available somewhere, always being shared by someone, always online. The internet is at the core of its communications strategy.

It uses not only "official" accounts controlled within Syria and Iraq, but also a huge network of supporters who see the internet as a kind of virtual frontline that demands as much effort and attention as the physical fight on the ground. Many supporters who can't make it to the war zone have talked about being involved in the "online jihad".

That means that every tweet, video and sermon is shared and magnified in a way that is exceptionally difficult to track and stop. Researchers say that IS supporters have used at least 46,000 Twitter accounts, external.

How has IS avoided detection and evaded being closed down?

Islamic State's brutal tactics have sparked fear and outrage across the world

It wants to be detected - because its social media presence is at the core of spreading its message. Many of its core online operatives expect their material to be targeted. Creating new accounts is just part of a day's work for them.

Some supporters follow a self-destructing strategy of deleting old accounts and creating new ones before police can catch up. There are special accounts that broadcast where and how to find the message and, crucially, it isn't fussy about where it posts it.

Twitter, YouTube and Facebook are the most well known spaces - but IS uses a huge variety of different services simultaneously.

How successful is the international effort to remove material?

Scotland Yard: Home of the UK's anti-IS online team

It's very patchy. Europol already has a special intelligence database containing details of thousands of documents and individuals related to spreading online violent extremism and terrorist propaganda.

London's Metropolitan Police works with companies to remove 1,000 pieces of extremist content a week.

Some of its targets are internet services overseas where police haven't already taken steps.

The Europol-run Internet Referral Unit, external is to do some of the same at the Met's team but on a continental scale. But its success ultimately comes down to whether internet companies will remove material quickly enough.

How good have internet companies been at removing material?

Again, the response has been patchy. There are no agreed industry standards for the identification, removal and referral of terrorism-related material online.

Some small organisations say that can be too too much for them to deal with. The largest, such as Google's YouTube, say they need the community to report and police content, although their critics say they could invest more effort into taking down material.

Some governments have a very strained relationship with internet companies in the wake of the Edward Snowden internet surveillance affair.

Why don't companies check content before publication?

IS on Youtube: Videos posted to spread message and win recruits

Internet companies say they are not censors, nor are they geared up to do that job.

YouTube receives up to 400,000 hours of new video every day.

Crucially, all the evidence shows that stopping the IS message on one platform only means it gets out elsewhere.

A lot of content is shared directly between individuals, often using a new generation of apps that include high levels of encryption. So while the new Europol scheme will see content being removed, there will always be somewhere else it pops up.

So what's the answer?

The EU thinks the only way forward is to avoid playing a game of "whack-a-mole", by which it means constantly closing accounts only to see them appear elsewhere.

Instead, it hopes the new Europol team will help identify the core social media presence of any extremist organisation so that national governments can better challenge it.

That's the theory, but so far all the available evidence suggests that IS cannot be taken offline.

- Published22 June 2015

- Published28 March 2018