Greek debt crisis: A country on the brink

- Published

Time is ticking for Greek PM Alexis Tsipras

The eurozone is facing its gravest crisis in its 16-year history. Greece is on the verge of defaulting.

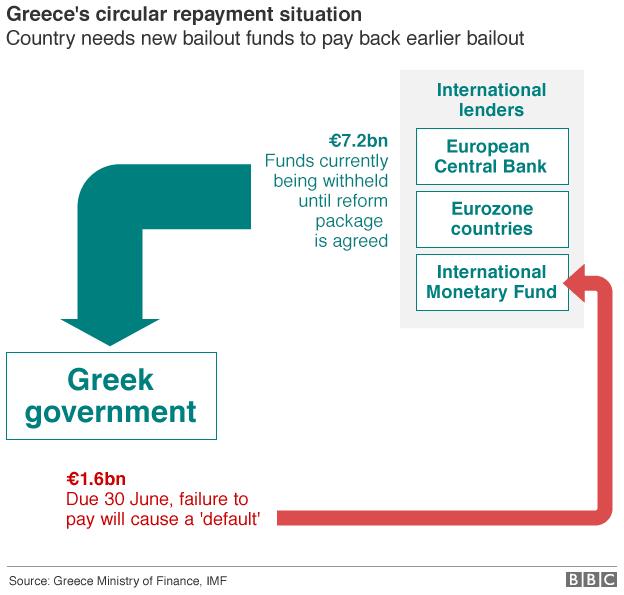

Almost certainly it will fail to repay a loan to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Tuesday. The risk of Greece leaving the eurozone has increased significantly. Both Europe and Greece have entered a period of turbulence with neither side in control of events.

Neither the government in Athens nor Europe's leaders are in a position of their choosing. The past few weeks and months are a story of stubbornness and grandstanding. Above all it has been a failure to reconcile two narratives.

After the election in January which brought the radical left party Syriza to power, Europe's leaders were determined that the new Greek government should live up to the commitments agreed by the previous administration.

Europe wanted to send a message that the eurozone could not be buffeted by elections and the popular vote. They also were worried that populist parties elsewhere in Europe could demand an easing of austerity and the eurozone's rules.

Alexis Tsipras, the new Greek prime minister, believed that austerity had failed Greece. The economy had shrunk 25% in five years and, in his view, had sparked a humanitarian disaster.

He had promised an end to austerity - a promise that he was not in a position to keep because other democratically elected governments in the eurozone had voters too.

They were not willing to finance Greece any longer without substantial reforms.

Party before country?

The arguments have raged for five months. The Greeks had their red lines. They would not adopt any new measures that deepened austerity, and they needed a commitment to discuss debt relief.

They made some concessions on taxes and pension reform, but they were not enough for the EU-IMF creditors. Trust had all but vanished; they doubted the reforms would be implemented.

Finally on Friday, the EU and IMF made their final offer: a five-month extension to the bailout programme with €12bn (£8.5bn) in funding, but with the condition that new reforms had to be accepted.

A withdrawal of funding could plunge Greece into chaos

Alexis Tsipras was not confident he could get the deal through parliament and, most importantly, hold his fragile coalition together. His opponents say that in opting for a referendum, he has put his party above the country.

The referendum announcement stunned Europe's leaders. Some finance ministers learnt of it on Twitter. Not surprisingly, they decided that the poll essentially ended the negotiations. Some ministers say that they were close to reaching a deal - 98% there.

Greek weakness

Greece was facing a deadline. It needed to find €1.6bn to repay the IMF on Tuesday. On Saturday, it argued for an extension to the existing bailout at least until after the referendum a week on Sunday.

I spoke to a Greek minister early on Saturday and he was confident the extension would be granted, but the eurozone's finance ministers were no longer prepared to play ball. It means that almost certainly Greece will default on Tuesday.

There has been a steady withdrawal of funds from Greek banks

Greece's weakness is its banks. There has been a steady withdrawal of funds. It continued on Saturday. There is not a bank run as yet, but billions of euros have been withdrawn in recent weeks.

Greeks have now heard that the European Central Bank (ECB) may not continue the emergency funding of Greece's banks.

Without it, Greece may have to impose capital controls as early as Monday, restricting what funds can be withdrawn or taken out of the country.

It is the most important decision in the ECB's history.

A withdrawal of funding could plunge Greece into chaos and yet the ECB cannot break its own rules by funding a banking system where the country is heading for a default.

One minister told me on Saturday that their greatest fear was a bank run and political divisions.

Playing poker

Beyond the uncertainty of Tuesday lies the referendum on 5 July.

The question will be whether the people support or reject the latest EU-IMF offer.

Alexis Tsipras will campaign energetically for a No vote. It will be a short but abrasive campaign. Europe will insist that the referendum is a choice between staying in the euro or returning to the drachma.

One minister said to me on Saturday: "[German Chancellor Angela] Merkel can define the referendum in Germany, not in Greece, and we have made it very clear that we want to stay in Europe and this is not about the eurozone."

Perhaps. It is worth remembering that a majority of Greeks have always wanted to stay in the euro.

If Prime Minister Tsipras loses the referendum, then his political authority will have been lost. There will be pressure on him to resign. If he wins, then he will return to Europe's leaders and say that he has a fresh mandate from the Greek people.

Once again, there will be negotiations with the outcome uncertain and against a background of a deteriorating economy. Another large bill - the maturing of ECB bonds - lies ahead on 20 July.

Alexis Tsipras has gambled both with his future and that of his country. He committed Greece to a vote, but only after the current bailout has expired, so leaving Greece vulnerable and exposed.

Austrian Finance Minister Hans Joerg Schelling said of the Greek government that "they were playing poker, but in poker you can always lose".

Greece timeline: Key dates ahead

30 June: Troika bailout programme ends as Greek €1.6bn payment to IMF due

1 July: No bailout programme could mean no emergency liquidity from the ECB

5 July: Proposed Greek referendum

10 July: Treasury bills worth €2bn to be repaid

20 July: Bonds worth €3.5bn to be repaid to eurozone partners

20 August: Bonds worth €3.2bn to be repaid