Greek debt crisis: What was the point of the referendum?

- Published

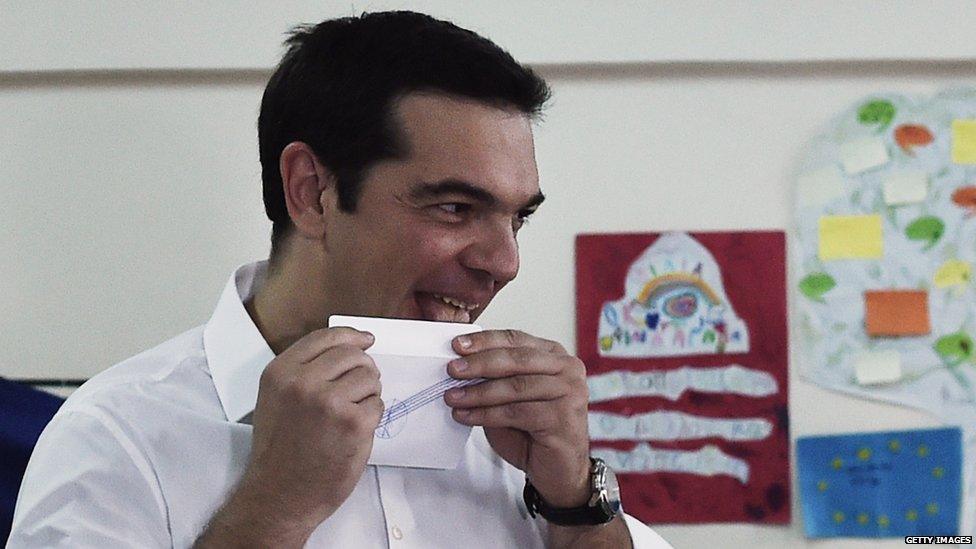

A week ago Alexis Tsipras voted "No" to austerity and now appears to say "Yes"

Just over a week ago, Alexis Tsipras stepped on to a podium in Syntagma Square in Athens. In his trademark open-necked white shirt, his sleeves rolled up, he punched the air.

"I call on you to say a big 'no' to ultimatums, 'no' to blackmail," he cried. "Turn your back on those who would terrorise you."

His thousands of fans roared in approval. The Greek public followed his lead and 61% voted "oxi" ("No").

Roll forward seven days and Greece's prime minister signed the very measures he had fought against. Corporate tax and VAT will rise, privatisations will be pursued, public sector pay lowered and early retirement phased out.

In a late-night speech to parliament, a chastened Alexis Tsipras compared negotiations to a war, in which battles are fought and lost.

"It is our national duty to keep our people alive and in the eurozone", he said. There was not a fist-punch in sight.

The old adage of a week being a long time in politics could not be more relevant. But even for us Greece-watchers, the past few days have left us scratching our heads.

'Northern European elite'

Almost a week after the referendum, banks remain closed

How could the man elected on the basis of ending austerity and tearing up the hated bailout have just applied for a third loan and signed off on some of the most austere measures in months?

Will the real Alexis Tsipras please stand up?

"When we started five months ago, it was very difficult to realise how this thing that we call the European Union was going to behave," says Dimitris Tsoukalas, general secretary at the interior ministry.

"We, the government, thought we could convince them that a country in this mess could take a completely different path. But it wasn't possible."

He sighs, flicking through the recently signed document of reform measures.

"We couldn't overcome the bankers and northern European elite who have absolute power in this continent."

But wasn't the referendum a complete waste of time, money and emotion, I ask?

"Not at all", he tells me. "The European leaders didn't want Tsipras - they wanted to cast him aside. But our victory in the referendum was a mandate for him to continue to negotiate.

"This was a Greek pride issue, to say 'no' to Schaeuble [the German finance minister] and Juncker [the president of the European Commission], when they wanted us to vote 'yes'."

Tsipras 'a hero'

Did the referendum raise false hopes?

I ask whether the idiosyncratic exercise in democracy was worth it; to have banks closed, Greece back in recession and Alexis Tsipras seen in Europe as the black sheep.

"That might be the case for European politicians. But for a great part of the people of Europe, Tsipras is not the black sheep - he is a hero."

In truth, criticism of Greece's prime minister is growing on both sides: from those who berate him for breaking pre-election pledges and going back on the referendum result.

On the other, from those who point out that a deal weeks ago would have avoided the nightmare of the past fortnight, with queues at bank machines, businesses haemorrhaging money and the need for even deeper austerity to redress the balance.

"Ultimately the referendum won time for the governing party", says Nikos Dendias, a former minister with the opposition centre-right New Democracy party.

"Remember Syriza is an ex-hardline splinter group. Ten days ago, Tsipras wouldn't have been able to get the agreement through his own party. But with the delay, it made a huge difference."

Alexis Tsipras is in an impossible bind: pushed to an agreement by the creditors, or face leaving the euro, but pulled away from one by his own voters, who cry treason.

"The prime minister is pretty vulnerable," says Nikos Dendias. "Unless he proceeds quickly, creating growth and development, this could ruin his 'prime ministership' within 12-18 months."

Ultimately, Greece was backed into a corner; the banks are still its Achilles' heel. If the government had walked away from a deal, the European Central Bank would have turned off its lifeline this week - and Greece would soon have been printing its own currency.

Yes, Alexis Tsipras was elected pledging to reverse budget cuts. But he was also voted in by vowing to keep Greece in the eurozone.

And that was one promise he could never have broken.

- Published11 July 2015

- Published11 July 2015

- Published10 July 2015

- Published10 July 2015