Matterhorn: The race to conquer Swiss 'Z Hore' mountain

- Published

Switzerland is marking the 150th anniversary of the first ascent of its most famous mountain.

The Matterhorn was first climbed on 14 July 1865 by English climber Edward Whymper.

It was an event that attracted worldwide attention and controversy, and, some say, helped the Swiss village of Zermatt become the hugely successful resort it is today.

In the mid 19th-Century, the sport of alpinism was growing in popularity, particularly among the young men of the British upper and middle classes, who were keen to include some mountain climbing in their grand tour of Europe.

By 1865, the great pyramid of the Matterhorn was one of the few unconquered peaks, and Edward Whymper, just 25 years old at the time, had his eye on it.

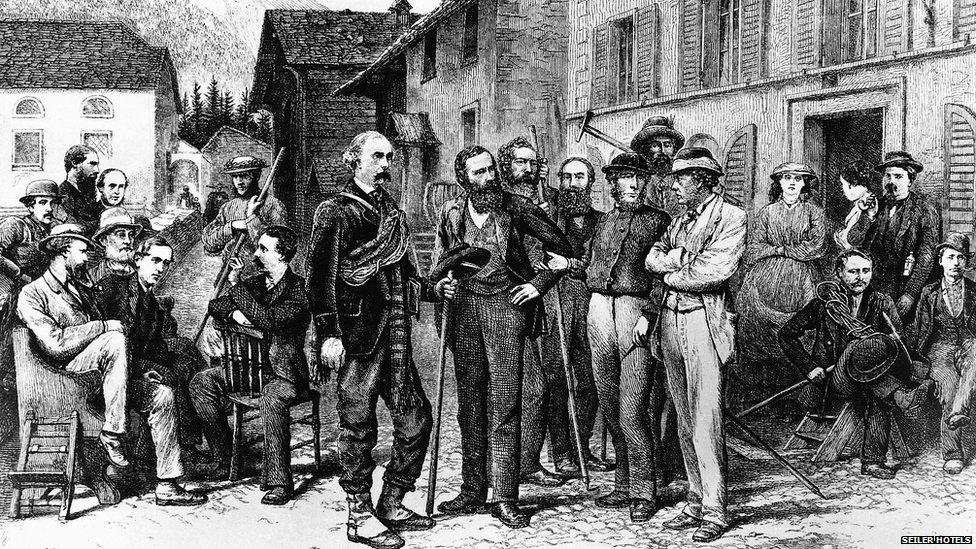

Alpinism became a popular sport in the 19th Century

He had hoped to attempt the ascent from the Italian side, together with fellow climber and mountain guide Jean-Antoine Carrel of Italy, but the plan collapsed when Carrel opted to accompany an Italian climbing party instead.

The competition to be first on the summit was fierce, not just between individuals, but between nations, and Italian sponsors of Carrel's group are thought to have bought off all the other local guides to prevent Edward Whymper from starting his ascent.

In desperation, Whymper arrived in Zermatt, looking for Swiss guides.

Zermatt at the time was one of the poorest villages in the Alps, completely cut off in winter and populated primarily by subsistence farmers. Many were deeply suspicious of the arrival of strangers in their midst.

"People were poor," explains director of tourism Daniel Luggen. "When the first visitors arrived in Zermatt, the local people were afraid the visitors would eat all the food and that they wouldn't have enough to survive the long winters."

Many locals firmly believed the Matterhorn could not and should not be climbed. Superstition was rife, and it was commonly believed that the Matterhorn, which villagers called "Z Hore" ("the peak"), was populated by ghosts and evil spirits.

Nevertheless, there were a few men in Zermatt who were ready to help the "British adventurers". Among them were Peter Taugwalder and his son Peter Jr, both experienced mountain guides.

But, to Edward Whymper's frustration, other British climbers were already in Zermatt, also planning an attempt on the Matterhorn, and demand for guides was fierce.

Edward Whymper (top right) in a 19-Century picture bringing together characters involved in the first ascent of the Matterhorn

In the end, the different groups decided to climb together, with Whymper and Lord Francis Douglas joining forces with the Reverend Charles Hudson and his protege Douglas Hadow.

The two Taugwalders were guides and porters, together with a French guide, Michel Croz.

They took what is today the most common route up the Matterhorn, via the Hoernli ridge, 1,000m (3,280ft) of very steep, very narrow rock.

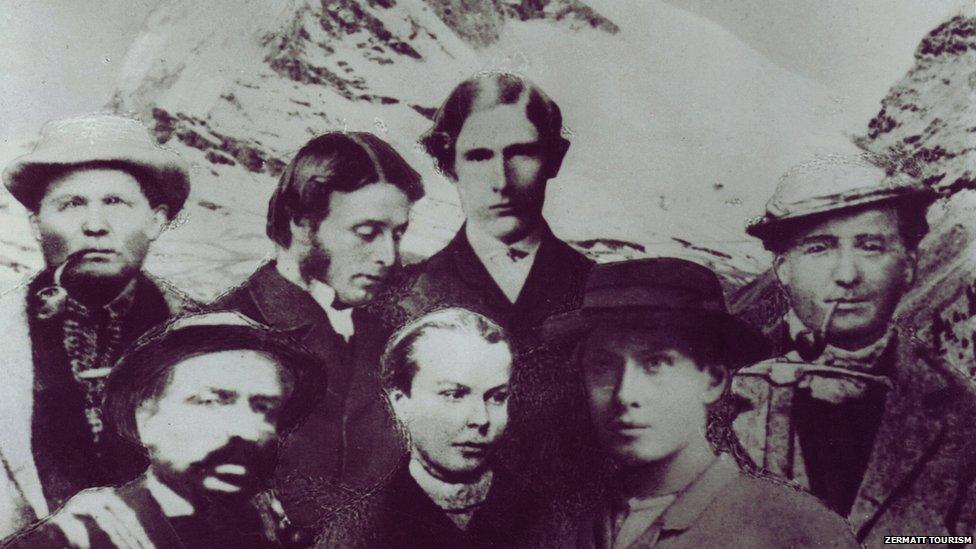

Matthias Taugwalder tells the story of the climb and why his ancestors were not to blame for the deaths

Matthias Taugwalder, who has climbed this route himself, describes it as "like walking on an ironing board, with a 2,000-metre drop on each side".

"If you slip, your only choice is which side to fall: Switzerland or Italy," he says wryly.

But Whymper's climbing party made good time, and by early afternoon the summit had been reached. Whymper and Croz are said to have detached their ropes, running the last few metres to the top.

Once here, they could see the unfortunate Italian group below them, and Whymper gleefully threw rocks down towards them to let Jean-Antoine Carrel know he was too late.

Down below in Zermatt, people watching through binoculars cheered as they saw Whymper and his colleagues waving from the summit.

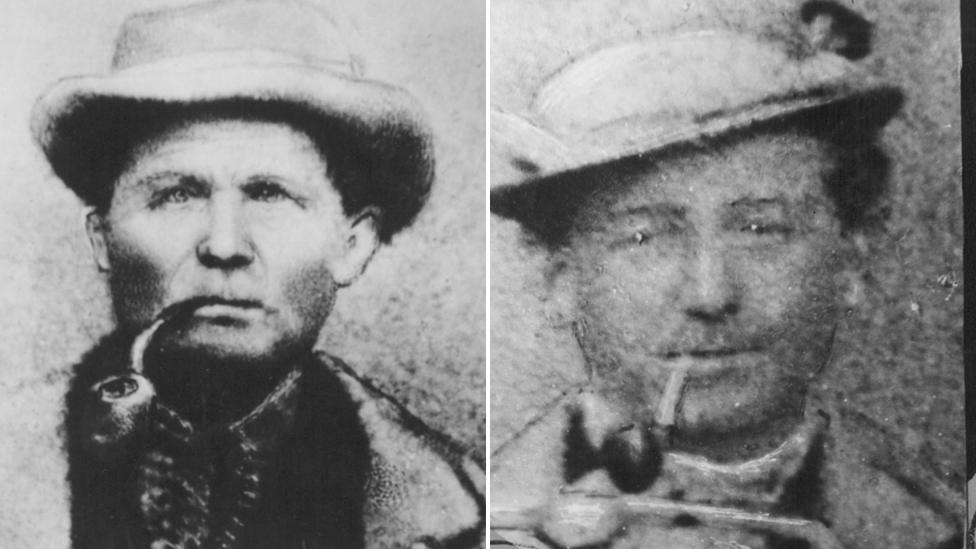

After the accident, there were claims that Peter Taugwalder Sr (L) had cut the rope to save his son's life

But the victory celebrations were short-lived. On the descent, Douglas Hadow's lack of climbing experience became clear, and Michel Croz, climbing below him, had to place Hadow's feet in every foothold.

"At one moment, Hadow slipped," explains Matthias Taugwalder, "and he dragged three other climbers (Croz, Douglas and Hudson) with him.

"Peter Sr had his rope wound around a rock, so he had a safe stance, but then the rope broke."

Whymper and the two Taugwalders were the only survivors of the first ascent of the Matterhorn and, as news of the tragedy spread around the world, controversy grew.

Queen Victoria lamented that "England's best blood has been wasted" and suggested mountain climbing should be banned.

In Zermatt, recriminations and investigations followed. Edward Whymper gave conflicting accounts, at times saying the guides should not be blamed, at others hinting that Peter Taugwalder Sr had actually cut the rope in order to save his own life and that of his son.

What really happened?

Neither Peter Taugwalder Sr nor Jr could speak English, and Peter senior could not read or write, so their ability to give an account of what happened was limited. Edward Whymper, however, wrote extensively, and over time his accounts increasingly suggested that Peter Taugwalder Sr had been at fault.

The official investigation cleared Peter Taugwalder Sr of any wrongdoing, but his climbing career was over, and after the accident he emigrated to the United States, only returning to Zermatt as an old man, where he died in poverty.

Matthias Taugwalder studied all the documents relating to the climb, because he and his family felt it was wrong that, although three people returned from the Matterhorn alive, there was only ever "one hero", Edward Whymper.

Matthias now firmly believes the real truth is that Peter Taugwalder Sr "very likely saved Edward Whymper's life", by standing fast as the four other climbers below them tumbled to their deaths, and then by guiding Whymper down the mountain.

An open-air play to mark the anniversary highlights the difficult relationship between the wealthy young British climbers and the poor local farmers hired to guide them

As part of the 150th anniversary celebrations, an open-air play, The Matterhorn Story, based on the different accounts of the first ascent is being performed in Zermatt, featuring many local amateur actors, including some from the Taugwalder family.

The play exposes the difficult relationship between the wealthy and ambitious young British climbers, and the poor local farmers they hired to guide them up the mountains.

"One of the goals is to show the world that without the guides, Whymper would not have reached the peak," says Mr Luggen.

"I think it needed both. It needed the pioneering spirit of the British coming here and it needed the hard work of the guides, so the first ascent of the Matterhorn is definitely a team achievement and not the achievement of a single person."

- Published24 April 2015

- Published17 July 2012

- Published9 April 2012