Greece debt crisis continues to expose European divisions

- Published

When it was done, when the 17 hours of negotiations had dragged out an agreement, French President Francois Hollande said: "We had to preserve French-German relations."

It had to be said, but few believed it. The Greek crisis has exposed a fault line: France and Germany do not share the same vision of Europe.

Gen Charles de Gaulle had described Europe as "a coach and horses, with Germany the horse and France the coachman". The two countries together are the engine room behind the European project.

After Angela Merkel won her third election, in 2013, she was crowned "Frau Europe". The Allgemeine Zeitung paper commented: "On this continent, everything will require the consent of Angela Merkel."

Even Le Monde, recognising that the French-German relationship was undergoing a fundamental change, wrote: "Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany, Chief of Europe".

Germany was a reluctant colossus, but it had become Europe's indispensable nation.

Power shift

It was summed up in this exchange a few years ago between Mrs Merkel and President Sarkozy of France.

Mr Sarkozy had turned to Mrs Merkel and said "We are made to get on. We are the head and legs of the EU."

"No, Nicholas," the German chancellor is said to have replied, "you are the head and legs. I am the bank."

So power shifted in Europe. France may have had a certain idea of Europe, even a vision, but Germany had the economic muscle.

Mr Sarkozy and Mrs Merkel - which of their countries is "the head and legs" of Europe?

When it came to the Greek crisis, two different motives were driving France and Germany. The French president believed in the Europe of solidarity; the German chancellor believed in a Europe of rules and responsibility.

In the recent Greek saga, France was not just the mediator between Germany and Greece. It advised Greece on its last proposal, which it quickly described as "sensible and credible". Berlin bridled at this.

'Brutal' tactics

It was not long before a German paper suggesting Greece take a "timeout" from the eurozone surfaced during the summit.

Francois Hollande dug in. "There is a rather strong pressure for a Greek euro exit. I reject that," he said. He dismissed the idea of a temporary Greek departure. "There is Greece in the eurozone or not in the eurozone, but in that case Europe retreats," he said.

The French lifted the argument above the detail of pension reform and VAT increases. This was about the future of the European project, and if Greece departed it would mark the end of European integration.

The French advised the Greeks on their last proposal

For the Germans it was about trust. They no longer believed that the Greeks would implement what they agreed to.

Mrs Merkel was determined that in exchange for a third bailout, Greece was locked into a reform programme. But in so doing, it has enabled others to brand the German tactics as "brutal" and enabled the Greeks to present themselves as victims of blackmail.

The economist Paul Krugman, who has been a consistent critic of German-led austerity, described the deal as a "grotesque betrayal of everything the European project was supposed to stand for", external.

Will it work?

The division between France and Germany has continued. The French parliament agreed - even before the Greek parliament voted - that the Greek proposal could pave the way for talks on a third bailout. The Bundestag, the lower house of the German parliament, is meeting only on Friday.

The French Prime, Minister Manuel Valls, said: "We are demanding a lot of the Greeks, not just to punish them, but to accompany them through a vital recovery."

As negotiations with Greece continue, the bigger question is whether this new bailout will work. I find very few believers.

The clock continues to tick for Greece

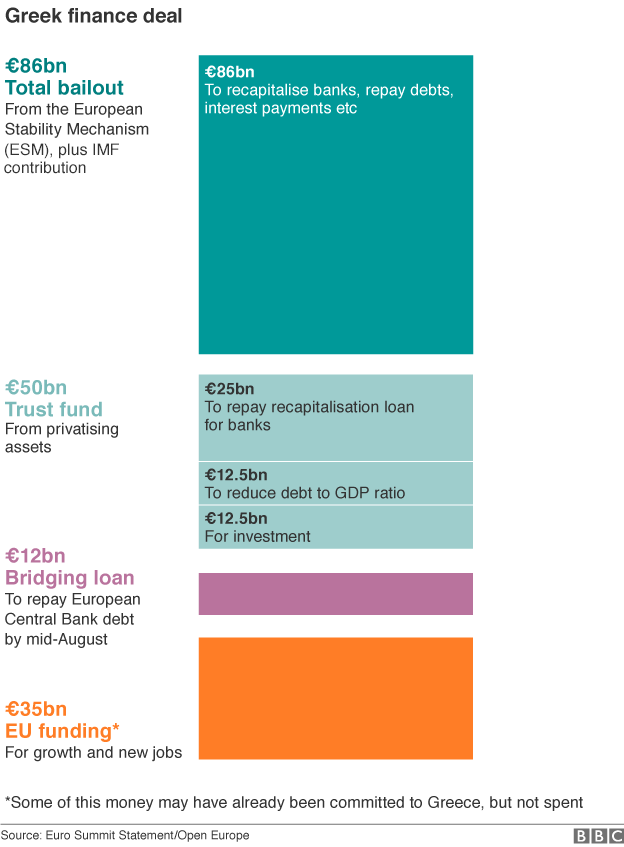

More money is being lent to a country deep in debt. The economy, this year, will contract by between 3% and 5%, and yet some of the new measures, in the short term, will only depress the economy further.

The whole plan depends on Greece delivering a sustained fiscal surplus, which seems unlikely.

The recapitalisation of the banks is dependent on the privatisation of some of Greece's most valuable assets. Previous privatisation programmes have run into the sand.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has indicated it believes Greece's debt is "highly unsustainable".

And to cap it all, the German Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schaeuble, said that many in the German federal government were "pretty well convinced that a [Greek exit] would be a much better solution for Greece".

So the Greek question may return. It nags away at the essence of the European project.

Will it remain caught in a halfway house between further integration and preserving the nation state? Or will it use this crisis to propose a tighter union?

What is clear is that France and Germany are managing Europe but they do not share an idea for its future.

In his statement at the end of the summit, the French president said that Europe "first and foremost must be European" and must not be "at the service of one public opinion or one 'national' parliament".

In other words, Germany should not define the argument.