Freediving: The lure of the deep

- Published

Freediving is like "a journey out of time", says champion diver William Trubridge

The cold, dark waters more than a hundred metres below the surface of the ocean are not a forgiving environment for human beings. The pressure, more than 10 times that at the surface, can quickly cause unconsciousness - fatal at that depth.

But for freedivers - a small band of extreme sportsmen and women who propel themselves down in no more than a wetsuit - the deepest part of the dive is not even the most dangerous. That comes as they ascend to the surface, sustained by a breath taken several minutes before, when a diver can succumb to so-called "shallow water blackout" just metres from fresh air.

Natalia Molchanova, widely regarded as the best female freediver in the world, took a deep breath on Sunday and dipped beneath the waves off the coast of Ibiza. She had done this countless times, but this time she didn't resurface. On Tuesday, the International Freediving Association (AIDA) released a statement saying Ms Molchanova was missing, and she is now presumed dead.

Ms Molchanova was not performing a deep dive. If anything, Sunday's dive was completely routine. According to the AIDA statement, she was at just 30m-40m - well short of her record depth of 127m. She was however performing a kind of dive called Constant Weight Apnea Without Fins (CNF) in which the diver wears just a weight belt and thin wetsuit. It is thought that she was caught in a strong underwater current and, without any fins to help propel her, was unable to fight against it. The search for her body continues.

Natalia Molchanova, who is feared dead, is widely regarded as the world's greatest female freediver

So what then is the attraction of swimming down into this harsh environment, where the whim of a deep invisible current can carry you away or the pressure of the water cause the gases in your body to produce hallucinations, unconsciousness, and eventually death?

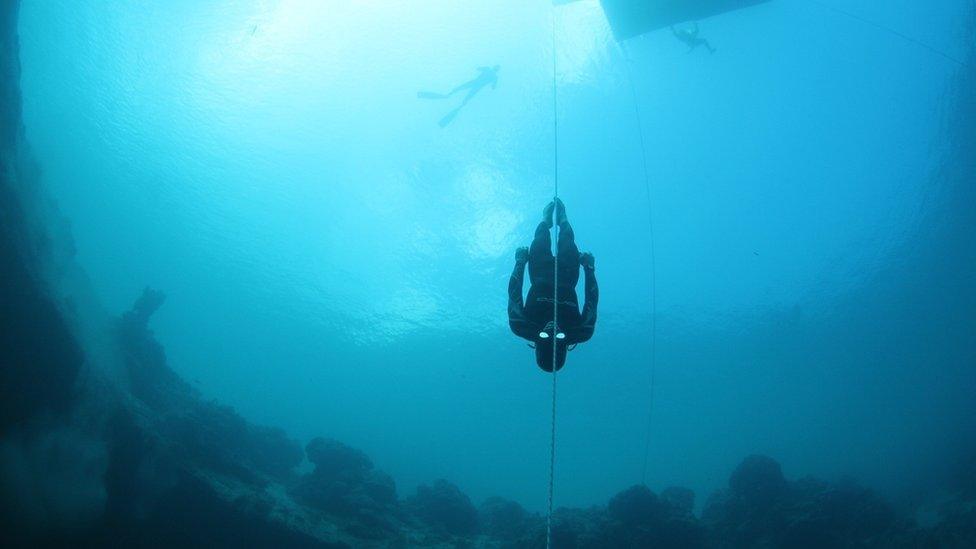

A film, external of the champion Kiwi freediver William Trubridge gives some sense of the lure of the deep. As the camera follows him down into the thinning light, his slow breast stroke is hypnotic. Even watching on a screen, there is a palpable sense of calm. "When you stop breathing you suspend the body's natural metronome, which it uses to count out time," Mr Trubridge told the BBC down the phone, "so holding your breath is almost like suspending time itself. A freedive is like a journey outside of yourself and outside of time."

At some point, a freediver's lungs become sufficiently compressed by the pressure change that the diver becomes negatively buoyant - they will sink without having to propel themselves. "It is the most peaceful part of the dive," said Mr Trubridge. "You are completely still and it is like you are expected. You are drawn into the ocean."

Stephen Whelan, a recreational freediver who runs Deeper Blue, a website devoted to the sport, echoed Mr Trubridge. "Freedivers go to incredible depths, they do incredible distances underwater, they hold their breath for seemingly inhuman amounts of time," he said. "But freediving is a very peaceful and relaxing sport. If you watch freedivers before they go under, it's about deep breathing. It's about getting into a calm mental state and staying calm throughout the dive. And it's a very introspective sport, the divers have to shut out the outside world. It's a sport of two extremes - you go to extreme depths but you also have to go deep into yourself to do it."

The best freedivers hold their breath for extraordinary lengths of time, perhaps three to five minutes on a deep dive but nearly twice that while lying still in a pool. They rely on something called the "mammalian dive reflex" - a reaction to cold water around the face that slows the heart rate dramatically and shifts blood from the extremities to the core of the body. The process - vital to water mammals such as dolphins but present in humans - allows freedivers to go for so long without air.

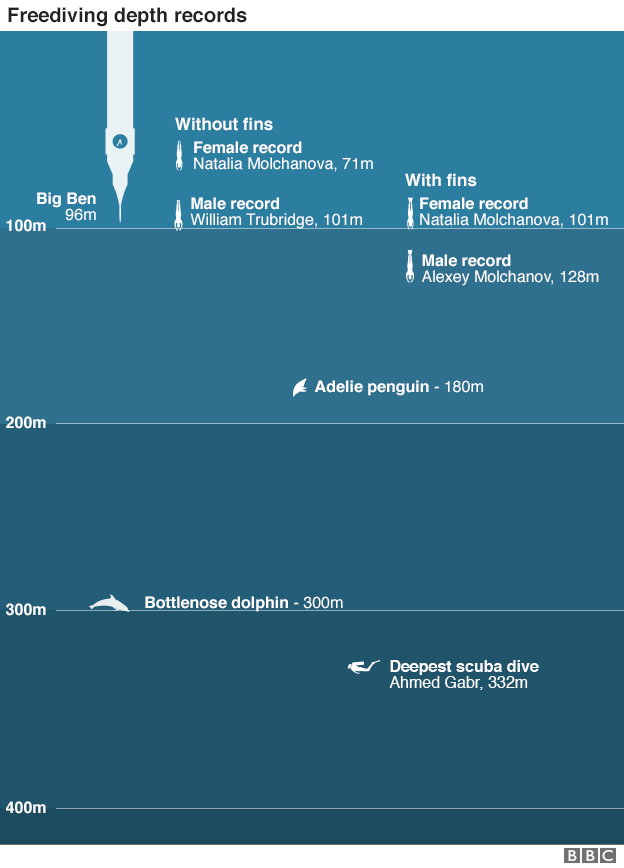

At nine minutes and two seconds, Ms Molchanova holds the world record for static apnea - holding your breath while lying face down in a pool. Her other records - of which there are many, external - are measured in distance: 71m for diving with a weight belt but without fins; 101m for the same dive but with fins; 127m for a kind of dive that uses a heavy weight to push the diver down. She held the female record in seven of the eight disciplines, external recognised by the AIDA, bested only by British diver Tanya Streeter who reached 160m in the most dangerous "No Limit Apnea" dive.

Deaths like Ms Molchanova's often provoke two sorts of reactions: tributes from the world of extreme sports and those who sympathise with the thrillseekers; and scorn from those who think the victims only have themselves to blame. Just a few hours after the story broke, Philip Gourevitch, a staff writer at the New Yorker, tweeted, external: "Natalia Molchanova, Champion Free Diver, presumed dead … because free diving is a "sport" like Russian Roulette is". Mr Gourevitch was rounded on for the insensitivity of his comments.

Freedivers can hold their breath for as long as five minutes as they descend and resurface

"Russian roulette is absolutely not true," said Mr Whelan. "It's an ill-informed comment from someone who should know better." And the statistics back him up: in more than 20 years of competitive freediving - and more than 50,000 competitive dives, according to the AIDA - only one person has lost their life. In 2013, Nicholas Mevoli, 32, of Brooklyn, New York, was attempting the same type of dive as Ms Molchanova when he lost consciousness on the way to the surface and later died. Out of competition, about five other people are thought to have lost their lives while training, most attempting the "No Limit" dive.

"It is not common that these accidents happen," said Kimmo Lahtinen, the president of AIDA. But experience is no guarantee against misfortune, he added: "When they do happen, they can happen to the most experienced divers because these are the people who are pushing the limits. That's what they do. It's like a paradox for me, when you are inexperienced you respect safe limits. When you are very experienced, you are on top of everything and you are really testing the human limits. Now Natalia, who was very very experienced, is lost."

Mr Lahtinen said he was surprised Ms Molchanova got into trouble on such a simple dive, and said he had never heard of a freediver being lost to a strong current. Ultimately though, he said, the ocean is stronger than even the most skilled diver.

"Accidents happen and sometimes they happen to the people who are superstars, like Natalia," he said. "When we are playing with the ocean we know who is the strongest, and we must respect that.

"Nobody expected this, but sometimes these things come out of the blue."

- Published5 August 2015

- Published12 January 2011

- Published13 June 2013