Ukraine crisis: Crimean Tatars uneasy under Russia rule

- Published

Lilya Budzhurova is ATR's deputy director in Simferopol

The lilac leather sofa still stands on the set of the ATR morning show in front of a wall decoration of giant paper flowers in matching tones. But the autocue screens are black and the cameras are off.

The Crimean Tatar TV channel is no longer permitted to broadcast from the peninsula, which was annexed by Moscow in March 2014.

ATR was a source of great pride to its team, a way of protecting and promoting their culture after years in exile. But during annexation, it also became a key critical voice.

"We showed an objective reality, not censored and not invented and they couldn't forgive that," says the channel's deputy director, Lilya Budzhurova.

"We showed what really happened in Crimea."

After Russia took control, all media had to re-register with Moscow. But ATR's application was returned with "mistakes" so many times, the channel was ultimately forced to flip the off-switch.

There had been earlier warning signs.

Ms Budzhurova was issued a caution by the prosecutor about "extremist" activity. The definition was "fostering anti-Russian views" and "fomenting distrust... towards the authorities".

But that distrust of Moscow is deep-rooted amongst Crimean Tatars.

Embracing Tatar culture has become fashionable for the younger generation

For 300 years, the peninsula that bulges into the Black Sea was home to the Crimean Khanate. The Tatars remained a significant presence until Stalin ordered their mass deportation in 1944.

It was a brutal, collective punishment for the collaboration of some with the Nazis.

The Crimean Tatars began their difficult homecoming in the late 1980s and today make up some 12% of the population. But hostility lingers and the Tatars boycotted the referendum on joining Russia.

Whilst most ethnic Russians did approve, the Tatars' stance dented the Kremlin's assertion that it was following "the people's choice".

Today, Russian President Vladimir Putin talks of outside forces playing up ethnic tensions to "destabilise" Crimea.

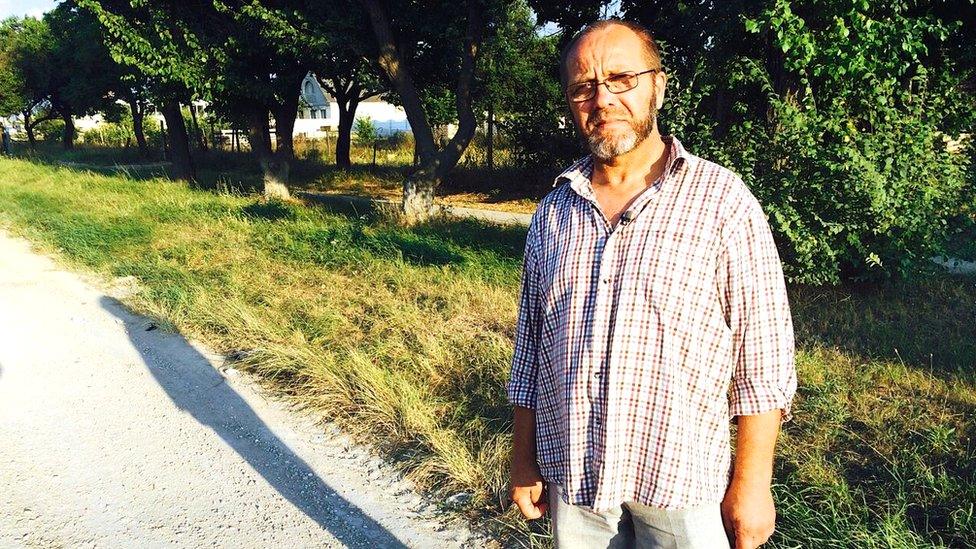

Abdureshit Dzhepparov stands by the road where his son and nephew were last seen almost a year ago, being bundled into a van

But several prominent Crimean Tatars remain in detention after a pro-Ukraine rally last year; two community leaders have been banned from returning home and at least seven people have simply disappeared.

"They'd just gone out to buy bread," Abdureshit Dzhepparov says, beside the busy road at the edge of Belogorsk where his son and nephew were last seen almost a year ago, being bundled into a van.

"He used to scrub his boots with a toothbrush and iron his laces, he was so pedantic. I can't imagine how he's coping wherever he is," Islyam's father says, switching tense constantly as he talks of his son.

'You don't talk out of turn'

Abdureshit Dzhepparov was one of the founders of his village, on land seized when they returned from exile. The families lived in dug-outs first, as they fought for the right to settle.

Investigators have hinted that Islyam's disappearance may be linked to his father's activism. Another theory suggests the pair were suspected of links to Islamic extremists. There appear to be no concrete leads.

And though the wave of abductions appears to have ended, unease clearly lingers.

"Of course, things have changed under Russia, when our children disappear," remarks an elderly man herding sheep in the street outside.

"Now you don't talk out of turn," Servet adds, before asking: "Are you recording that?" and laughing nervously.

A month after annexation, President Putin issued a decree on the rehabilitation of the Crimean Tatars; their language got equal status with Russian and Ukrainian as Moscow tried to woo the community.

Over a year on, there is still no concrete progress on critical issues like land rights, though Kiev never rushed to resolve such issues either.

"Ukraine only loved us after they lost us," Lilya Budzhurova shrugs. Kiev suddenly granted the Tatars "indigenous" status after annexation.

Young Crimean Tatars want to preserve their traditions, like this young couple who chose to marry in Bakhchisaray's 16th-Century Great Khan Mosque

And yet in the ancient heart of Bakhchisaray, the Crimean Tatars' deep roots are clear.

That history is what drew one young couple to the town last week to be married in the 16th-Century Great Khan Mosque.

"We need to preserve our traditions, or our future has no meaning," says Marlen, the groom, after a religious ceremony conducted by an imam in Crimean Tatar, peppered with odd phrases in Russian, like "central heating".

Marlen and his new wife, Lenora, admit they struggled to learn their own language; their young friends chatter in Russian. But embracing their Tatar culture is fashionable now.

So do they worry about their future, under Moscow's rule? "I would say yes," Marlen ventures. "Of course. But we'll be OK."

'I will be buried in this soil'

Some Crimean Tatars have clearly made their peace with the new reality, even joining the local pro-Russian government.

Tatar ancient roots in Crimea are clear in Bakhchisaray

Others talk in private of a belief that the peninsula will ultimately return to Ukraine, although calling for that publicly is illegal under Russian law.

And several thousand have voted with their feet, including many ATR journalists who have left for Kiev.

The channel has now begun broadcasting from there back into Crimea, and the team left behind provides pre-recorded content - though nothing political.

But after pouring her heart and soul into ATR, their feisty boss has no intention of leaving the land of her ancestors.

"Even if a tank drives over me, I will be buried in this soil," Lilya Budzhurova says. "And many people think this way."

- Published15 March 2015

- Published23 October 2012

- Published1 April 2015

- Published18 August 2015