Migrant crisis: Five obstacles to an EU deal

- Published

Hungary has become a migration hotspot in the heart of Europe, as thousands enter from Serbia

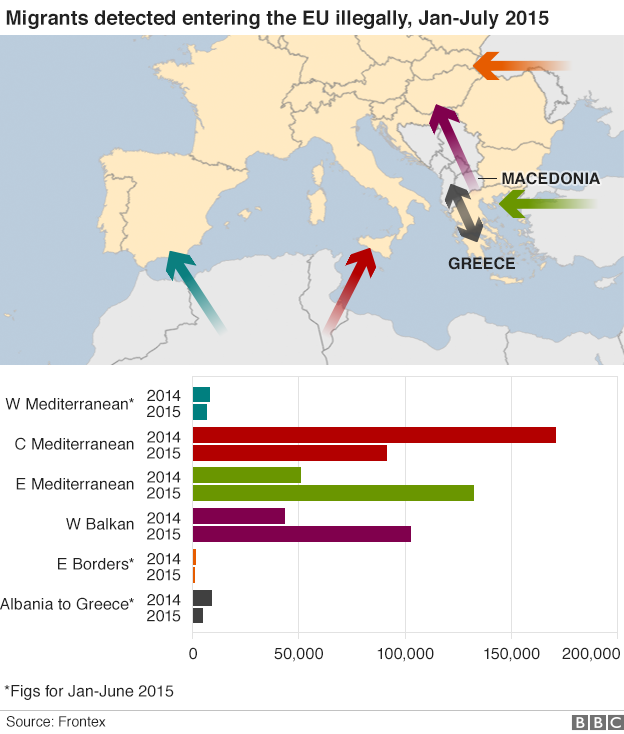

Europe is struggling with its biggest migration crisis since World War Two, with unprecedented numbers of refugees and other migrants seeking asylum in the EU.

The 28 EU interior ministers will hold an emergency meeting on the crisis on 14 September. July was a record month, with more than 100,000 reaching the EU's borders.

But it is proving difficult to get agreement on joint action, as migration pressure varies from country to country. What are the biggest obstacles to a solution?

Free movement arguments

Kos, Greece: Migrants from Pakistan are part of a huge influx in the Greek islands

The EU core principle of free movement - embodied in the passport-free Schengen area - is in dispute.

UK Home Secretary Theresa May called the EU migration system "broken", saying the Schengen system had "exacerbated" the problem of large-scale irregular migration.

The UK and Ireland are not in Schengen, but nearly all of their EU partners are, as well as some non-EU countries.

Nationalists across Europe, such as the National Front (FN) in France and Italy's Northern League, also blame Schengen for the ease with which many migrants have travelled from southern to northern Europe.

But the governments in France and Germany are among those who value Schengen for its contribution to the European economy. Schengen makes it easier for firms to hire workers from other EU countries, or to post workers abroad.

The principle of free movement also has huge symbolic value for the EU. East Europeans embraced it eagerly after decades of communism, when travel to the West was impossible for most ordinary citizens.

But Schengen members can re-impose border controls temporarily for national security reasons, for example if they face an extraordinary surge of migrants. There is pressure in the EU now to give authorities more discretion to do that.

Arguments over barriers

Hungary's razor-wire fence has not deterred many desperate migrants like these at Roszke

Hungary, which is in the Schengen zone, has built a 175km (110-mile) razor-wire fence 4m (13ft) high along its border with Serbia, which is outside the area.

The barrier will be strengthened in the coming weeks, but it is highly controversial. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius criticised it, in remarks rejected by the Hungarian government as "shocking and groundless".

In the first quarter of 2015 Hungary became a new migration hotspot, as thousands of asylum seekers saw it as an easier gateway to northern Europe.

Of the 32,810 asylum applicants in Hungary in that period 70% were from Kosovo. Most Kosovans are fleeing dire poverty, rather than political or religious persecution, so in most cases their asylum claims are rejected.

But now, many of those reaching the fence have fled the war in Syria and have legitimate asylum claims.

Trainloads of migrants are heading for Austria and Germany from Budapest - and Hungary's neighbours worry that it has merely shifted the problem on to them.

Bulgaria - not in Schengen - has also put up a razor-wire fence on its border with Turkey, to keep migrants out.

Spain's small territories of Ceuta and Melilla in North Africa are similarly fenced off.

The UK's investment in extra border security at Calais, in northern France, is less controversial, as the UK is not in Schengen and migrants have been risking their lives jumping on to lorries and trains.

But it suggests a growing "fortress Europe" attitude in the EU, contradicting the liberal values on which the EU was founded. Many Europeans cherish their hard-won democratic freedoms, and oppose the creation of new border fences.

Many also argue that, instead of erecting barriers, the EU should do more to tackle the people-traffickers who make huge profits from migrants' misery.

Quota disagreements

The rules governing immigration to the EU - explained in 90 seconds

EU ministers have rejected binding quotas for the distribution of refugees, despite the difficulties faced by Greece, Italy and Hungary. They are the main entry points for migrants crossing the Mediterranean and the Balkans.

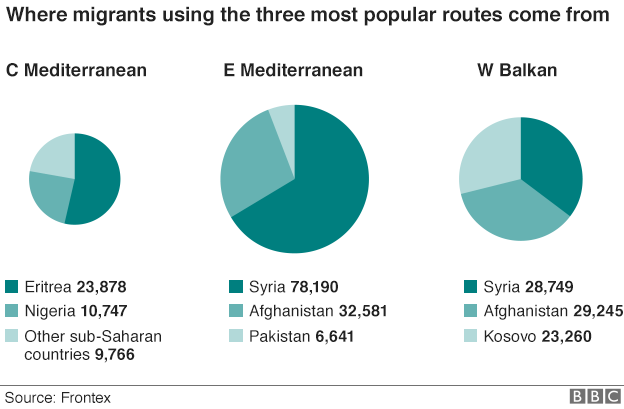

The European Commission urged EU governments to accept a mandatory "distribution key" to resettle 40,000 Syrian and Eritrean refugees. Instead, they agreed to accept 32,500 on a voluntary basis.

The UK has opted out of any quota system, amid a widespread hardening of attitudes towards immigration.

There are tensions in the EU over the whole European asylum policy, because of the disproportionate burden faced by some countries.

The EU is trying to adapt the rules, external to deal with the crisis, but politicians want to see rapid progress, not just long-term plans.

The controversial Dublin Regulation is under review, and Germany has stopped abiding by it.

Under Dublin, the EU country where an asylum seeker first arrives has a duty to process their claim. So if that migrant moves elsewhere in the EU he/she can be sent back to where they first arrived.

Extra EU help has been promised for the countries most in need. Of the €2.4bn (£1.7bn; $2.7bn) approved for the next six years, Italy is to get nearly €560m and Greece €473m.

The UK, France and Germany have called for migrants to be fingerprinted and registered when they arrive in Italy and Greece.

But the migration hotspots need more EU help, as their reception centres are overcrowded.

Burden-sharing is a divisive topic. Germany accepted by far the largest number of asylum claims last year and expects to see as many as 800,000 this year.

Sweden had the second-highest number, yet it has a far smaller population than the UK, which accepted fewer asylum seekers.

There are calls for eastern European countries to take in more asylum seekers. Slovakia argues that most migrants will still move to richer countries, where wages and welfare are better.

Arguments over conflict zones

Many Europeans are calling for much greater EU efforts to end the conflicts in Syria, Libya, the Horn of Africa and Afghanistan that are fuelling the exodus of refugees.

The UK government is among those arguing that the EU aid budget can help stem the flow of poor and desperate migrants seeking a better life in Europe.

The UK says it is contributing generously to refugee welfare in countries bordering on Syria, which are housing far more Syrian refugees than the EU. Most refugees, it is argued, want to go home as soon as peace and stability are restored.

And projects to ease poverty in sub-Saharan Africa can help to stem the considerable exodus from there.

But critics of the UK stance say those are longer-term goals, whereas the crisis demands urgent action and co-operation among all 28 member states.

Improving the economic prospects of young people in the Western Balkans - still recovering from war - could help stem the migrant surge from there.

Albania's Prime Minister Edi Rama says the EU should do much more to raise living standards in poor Balkan countries, which are negotiating to join the EU.

Albania, Bosnia-Hercegovina and Kosovo are all experiencing an outflow of frustrated citizens seeking a better life in the EU.

But EU countries cannot agree on the amount of aid those countries should get. There are fears that corruption could undermine aid projects - something that has bedevilled Kosovo.

Nationalist arguments

The Pegida movement in Germany rallies frequently against immigration and "Islamisation"

Nationalist parties and movements have played a big role in hardening attitudes towards immigration.

Far-right Jobbik won 20% of the vote in Hungary's 2014 parliamentary elections, making it the most successful anti-immigration party in Europe.

But even in the powerful, long-standing EU member states many mainstream politicians have taken a tough stance towards migrants.

The UK Conservatives are urging new EU rules to limit migrants' access to welfare benefits. The UK Independence Party, demanding strict border controls and exit from the EU, also has a strong following.

France's National Front has wooed many voters away from right and left. Meanwhile, ruling coalitions have done deals with the far-right Freedom Party (PVV) in the Netherlands and the Danish People's Party (DPP) in Denmark. In Finland, the nationalist Finns have entered government.

In neighbouring Sweden, which has an open-door policy towards Syrian refugees, support for the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats has soared to almost 20%.

Even in Germany - seen as profoundly loyal to EU values - nationalists and Eurosceptics have staged anti-immigrant marches, under the banner of Pegida, and have been elected to regional assemblies.

Insecurity about migrants is widespread in a Europe blighted by unemployment and welfare cuts. So politicians are anxious not to appear "soft" on immigration. It means less hospitality towards migrants, even genuine refugees.