Viewpoint: Munich migrant welcome shames Europe

- Published

Welcome to Germany: A new arrival tries on a policeman's hat

The biblical story of the Good Samaritan came close to reality in Germany last weekend.

A gap-toothed little Syrian boy beamed as he was allowed to try on a Bavarian policeman's hat.

An exhausted man, unshaven for three days, couldn't help wiping a tear from his eye.

A cheerful young man was a picture of good humour, making a heart sign with his hands.

There were heart-warming scenes at Munich's main railway station. People who had spent weeks fleeing were greeted with applause, sweets and soft toys - not by some political activists, but by many ordinary citizens.

Those citizens had set off for the station in Munich and other German cities to demonstrate to the refugees: "You're not lepers, you're welcome - we respect you for what you've had to endure".

There were thousands of small gestures, made possible because Chancellor Angela Merkel had decided on one big gesture: Germany will take in the Syrian refugees who were stranded in Hungary.

The refugees were treated badly in Hungary; in Austria they were waved through - and in Germany they were welcomed.

Banishing Hitler

It was touching and grand - it is historic. Munich is the big German reception centre, the place where refugees get first aid, from the state, from a well-run administration, from a mayor with a heart and from a hospitable civil society.

Such goodwill doesn't solve the many problems faced by the state and society in integrating the refugees.

But it helps to tackle those problems. And perhaps that goodwill is infectious.

Volunteers handed out soft toys and other goodies to refugee children

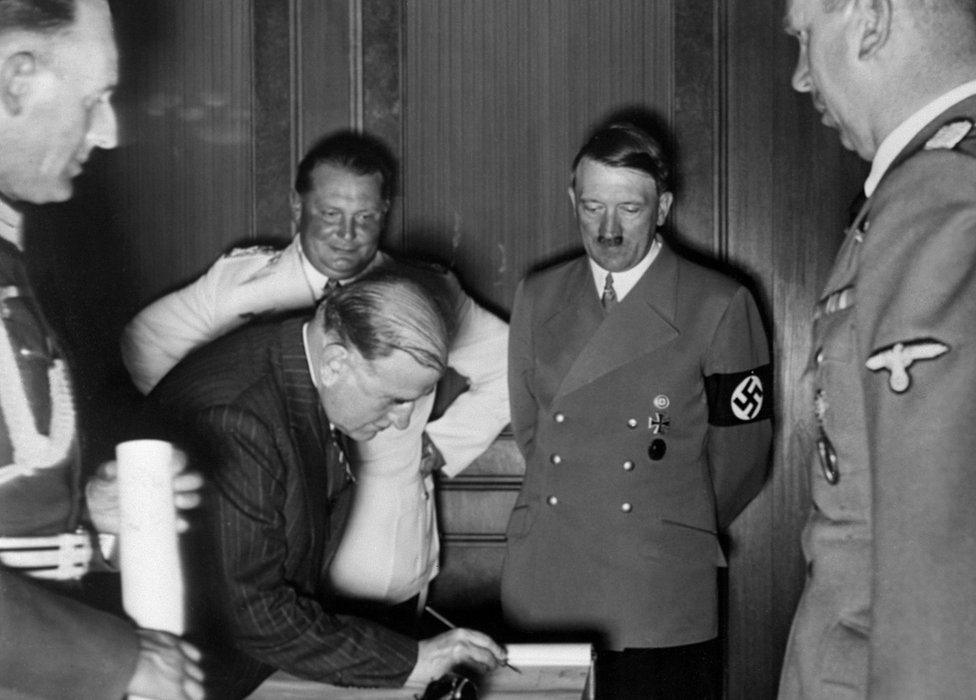

Munich was the city of the 1938 Munich Agreement - the Hitler diktat that set in train the destruction and break-up of what World War One had still left intact.

Now in 2015 Munich could establish a new tradition: Munich as the name and symbol of protection and help.

The Prime Minister of Upper Bavaria, Christoph Hillenbrand, said a really remarkable thing at the weekend - so different from what one expects a German official to say: "Legal issues right now are not so important to me."

Above all, for the man responsible for receiving refugees in the greater Munich area, it is a question of "humanitarian management".

The official is picking up on the new line of Chancellor Merkel. Rules and instructions, Mrs Merkel says, are not as important right now as flexibility and first aid. The concern of quite a few European politicians that this help will attract more refugees is disgraceful, she argues.

Germany is establishing an alternative to the policy of deterring refugees.

EU migration: Crisis in graphics

Hungary border echoes of 1989 and 1956

Munich Agreement, 1938: The notorious deal enabled Hitler to annex parts of Czechoslovakia

Far-right hostility

What's happened? Are we witnessing a miracle? Has Germany overnight become a paradise of charity? We should not exaggerate. German society, like in Europe as a whole, is torn between a willingness to help, a sense of helplessness, defensiveness and incitement.

Germany has an increasingly toxic anti-immigrant scene - their messages are marked by brazenness, death threats and incendiary language.

The threats are directed at refugees - "We'll burn you" - but recently they have also targeted politicians who stand up for refugees.

Last month a crowd in Heidenau hostile to migrants jeered Chancellor Merkel - one placard said "traitor"

Two weeks ago Mrs Merkel visited a migrant hostel in Heidenau, in the former East Germany, and got a sense of the hatred poured out by anti-immigrant activists. Her decision to accept refugees has to be seen in that light. She wanted to send a signal: Germany is no hotbed of neo-Nazis; Germany delivers help; Germany sets a good example for Europe.

Germany has two societies: one is enlightened, open, knowing that a good future depends on inclusion, and on making the four million Muslims living in Germany really feel at home. This generous society also knows that Europe cannot cut itself off and that a fortress Europe is absurd in a globalised world. Mrs Merkel is now in the vanguard of that civil society.

But alongside it is a second society, uncivil, noisy, hostile to foreigners, displayed in the so-called Pegida rallies in recent months.

Pegida is short for Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the West. It gathers up grievances extending from the extreme right far into mainstream, middle-class Germany. But the many attacks on migrant hostels (almost 300 this year) have discredited the movement.

Multicultural Germany

The big welcome for refugees in Germany is a reaction by bright, friendly Germany against dark, anti-foreigner Germany. But bright Germany has not yet won a final victory.

In the past decades Germany has become a multi-faith, multicultural country.

Turkish street food in Kreuzberg, Berlin - a district with a large Muslim community

In 1950 Protestants and Catholics accounted for 96% of the population in both Germanies - east and west. Just 4% were either non-Christian or non-religious.

Today the picture looks substantially different: about 60% are Protestant or Catholic, 30% are non-religious and 10% belong to other faiths. Half of the latter are Muslims. The Jewish community is 100,000 strong.

Germany has become a colourful country, a migrant destination - yet Mrs Merkel's CDU/CSU bloc for a long time resisted that. The battle is over and the reception of the refugees is meant to show that - it's a new Germany now. Still the CSU in Bavaria is resisting a bit, because it doesn't want to lose some right-wing voters.

The acceptance of refugees, through the chancellor's policy decision, was first a message to her own party, second a message to German society and third, to the other EU member states.

To her party it means: gone are the days when the CDU strongly opposed immigration. To enlightened civil society the message is: I am with you, I respect fundamental human rights and stand up for them courageously. To the EU the message is: Germany is setting an example, Germany is helping, and hopes that you follow this example.

EU wake-up call

It is also an attempt to overcome the inertia in European asylum policy and to tackle a problem that will be with us for a century.

Mrs Merkel is showing leadership. She was cursed over her policy on Greece, accused of a lack of pity, especially in southern Europe. Now Germany's policy on refugees is contrasting with that.

The current welcoming policy will not lead to a German open-door policy. Soon there will be curbs again on the acceptance of refugees. The big, sudden welcome was an exception for an exceptional situation. But it was an historic decision.

It recalls a phrase from the White Rose leaflets, put out by a group that resisted Hitler in Munich: "If everyone waits for somebody else to begin, then nobody will begin!" That phrase comes from a bitter period - but it doesn't just belong in the museum of anti-Hitler resistance. Everyone must ponder for themselves today what that means, and what duty that points to. That goes for the EU heads of state and government, too.

Prof Heribert Prantl is a senior editor at German news daily Sueddeutsche Zeitung, based in Munich.