How is the migrant crisis dividing EU countries?

- Published

Idomeni camp, Greece: For most migrants smuggled into Europe, life has become a harsh lottery

Big fault lines have opened up across the European Union - both east-west and north-south - because of the migrant crisis.

Many migrants want to get asylum in Germany or Sweden, but those countries want their EU partners to show "solidarity" and share the burden.

Many have fled the conflicts and abuses in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Eritrea.

But there are also many economic migrants fleeing poverty in the Balkans and countries like Nigeria and Pakistan.

Why is Europe so divided over migrants?

Greece

The Greek islands near Turkey are the main focus of EU attention, as thousands of migrants continue to come ashore there daily.

A rescue off Lesbos: Overcrowded migrant dinghies are a common sight

For months tensions have been escalating between Greece and some of its EU partners. They accuse Athens of deliberately waving through migrants who ought to be registered as soon as they enter the EU.

The row with Austria got so bad in February that Greece withdrew its ambassador to Vienna.

Greece insists that it cannot become Europe's holding centre for migrants - it demands fair burden-sharing.

In January-February this year more than 120,000 migrants arrived in Greece - out of more than 130,000 who crossed the Mediterranean to reach the EU, the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) said.

The total in just two months was nearly as many as in the first half of 2015.

So far this year more than 400 migrants have drowned in the Aegean Sea, highlighting how risky the journey is.

The EU has given Greece until 12 May to fix "serious deficiencies" in its control of the EU's external border in the Aegean.

Four extra reception centres - called "hotspots" - are nearly ready on the islands.

The EU plans to give Greece €700m (£544m; $769m) in emergency aid to tackle the crisis. It is the first use inside the EU of funds earmarked for humanitarian disasters outside the EU.

Turkey

Improving co-operation with Turkey on the migrants issue is a top priority for the EU.

But progress has been very slow. Meanwhile, people-smugglers in Turkey remain very adept at shipping desperate migrants across the Aegean, for extortionate fees.

Turkey is reluctant to readmit large numbers of migrants - but it is under intense EU pressure now to do so.

Under the current rules, only migrants who have no right to international protection can be sent back to Turkey. That means economic migrants.

The reason is that only one EU country considers Turkey "safe" for returning migrants. EU data shows that 23% of asylum claims from migrants of Turkish origin were deemed well-founded in 2014.

Turkey is demanding a high price for its co-operation, arguing that it has already spent €8bn helping refugees from the Syrian war. It is struggling with the influx, already housing 2.5 million in camps.

As a candidate to join the EU, Turkey wants to see real progress in its accession negotiations. The EU has pledged that, and is offering visa-free travel for Turkish citizens in the Schengen passport-free zone.

Historic tension between Greece and Turkey makes the Aegean operation to stem the migrant flow difficult - as does Turkey's long, zig-zagging coastline.

Macedonia

A migrant bottleneck has built up on the Greece-Macedonia border since Macedonia put up a razor-wire fence at the Gevgelija-Idomeni border crossing.

More than 10,000 migrants are camping in squalid conditions near the fence. Some - children among them - are sleeping rough in icy conditions, with little food or medical help.

At least 2,000 people queue for food every morning in Idomeni

Some of Macedonia's Balkan neighbours have sent border guards to help police the new flashpoint. Anger boiled over in early March, with migrants battering down a gate before police fired tear gas to chase them away.

Migrants continue flocking to the border because they want to get to northern Europe. Yet under the EU's controversial Dublin Regulation, external a migrant's asylum claim is supposed to be processed in the country where he/she first arrives.

Macedonia also hopes to join the EU, but this crisis is just adding to the obstacles in its bid.

Its migrant policy appears discriminatory: it has been letting in small numbers of Syrians and Iraqis, but not Afghans.

Hungary

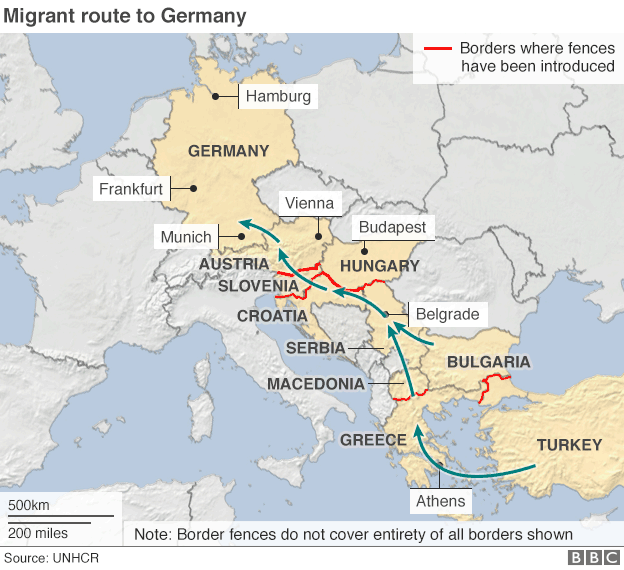

Last year Hungary became a gateway for migrants bound for Germany.

It became the focus of world attention when Hungarian riot police fired water cannon and tear gas at a big crowd of migrants at the border with Serbia in September.

Hungarian riot police clashed with migrants at Roszke on the Serbian border

There was widespread criticism of Hungary for its decision to build a razor-wire fence and prosecute migrants entering illegally. But many Hungarians supported their government's tough stance, according to reports.

After completing the Serbia section Hungary extended the fence to stop migrants entering from Croatia.

The conservative Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has said Europe's Christian heritage is under threat because most of the migrants are Muslims. He accused Germany of encouraging the influx by welcoming so many migrants.

Hungary and its northern neighbour Slovakia refuse to be part of an EU quota plan for distributing 160,000 migrants across the EU. They are currently in Greece and Italy - and so far fewer than 600 have been transferred.

The European Court of Justice is now considering a Hungarian-Slovak complaint against the EU.

Austria

Last year migrants poured into Austria from Hungary, en route to southern Germany. The authorities did not push them back.

But Austria re-imposed border checks - as did Germany on its border with Austria - as a temporary, emergency measure, allowed under Schengen rules. Slovakia - on Austria's eastern border - did so too.

The crisis caused major disruption to road and rail travel between Austria and its neighbours. Crowds of migrants gathered at Vienna's main stations, waiting for trains to take them north.

In the latest twist, Austria set new daily limits: a maximum of 80 asylum applications and 3,200 migrants in transit to other countries.

The European Commission has protested to Austria, saying those limits violate EU law.

Germany

Around 1.1 million asylum seekers arrived in Germany in 2015 - a record number. That put great strain on local authorities, who had to create emergency campsites.

Hanau, Germany: Soldiers were deployed to build temporary accommodation for migrants

Chancellor Angela Merkel says Germany will look after genuine refugees, fulfilling its international humanitarian duty.

That welcome does not extend to the many economic migrants. Those from Balkan countries like Kosovo, Albania and Serbia can now being sent back - Germany recently classified those countries as "safe".

Mrs Merkel has been much criticised for her "open door" policy on refugees. The critics include fellow conservatives, notably the Bavarian CSU party.

Last year there was an outpouring of sympathy and help for the new arrivals from many ordinary Germans.

But there were also many street protests by the right-wing Pegida movement, which claims to be defending Germany from "Islamisation".

There have been hundreds of attacks on migrant hostels - usually empty buildings allocated for new arrivals. In many cases they were gutted by fire.

Anxiety was fuelled by the Cologne attacks, when hundreds of women were assaulted at New Year, many of them sexually molested. Victims and witnesses mostly blamed gangs of migrant men from North Africa.

Germany wanted its EU partners to accept mandatory quotas, to spread the migrants EU-wide. France, Italy and Greece backed Germany on that - but EU leaders as a whole decided on a voluntary scheme.

France

French demolition squads have been tearing down migrant shacks at the "Jungle" - a squalid campsite in Calais, where about 4,000 migrants are hoping to get across the Channel to the UK.

Basic, clean shelters have been erected instead - but migrants yearning to reach the UK do not want to stay there, and are avoiding registration.

Flimsy migrant shacks have been torn down in a drive to bring order to the "Jungle" camp

The UK has immigration checkpoints at Calais and Dunkirk, under an agreement with France.

There have been warnings that France could end that arrangement if British voters reject EU membership in the UK's June in-out referendum.

Most of the Calais migrants are from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Eritrea or Sudan.

France re-imposed police checks on its border with Belgium after the November Paris attacks, in which jihadists murdered 130 people.

News that two of the killers had passed through Greece fuelled alarm about freedom of movement under Schengen.

Marine Le Pen's National Front (FN) is a major force in French politics - it is anti-EU and deplores mass immigration.

Italy

Last summer Greece became the main Mediterranean gateway for migrants - previously it had been Italy.

Several factors have made it riskier for migrants to head for Italy by boat: hundreds have drowned in repeated disasters at sea; war-torn Libya is extremely dangerous; the voyage is longer - even to Lampedusa, a tiny island near Tunisia.

More EU resources have been put into Frontex, the border agency now monitoring migrant routes from Libya. But EU officials say a bigger effort is needed, as the sea area is vast.

Italy is angry that some EU partners are so unwilling to share the migrant burden. Its reception centres - especially in Lampedusa and Sicily - are overcrowded, like those in Greece.

Denmark and Sweden

The Danish stance on immigration is among the toughest in Europe. Controversially, Denmark has given police the power to seize valuables worth more than 10,000 kroner (€1,340; £1,000) from refugees to cover housing and food costs.

In January Sweden introduced identity checks for travellers from Denmark in an attempt to curb migrant numbers.

The clampdown has slowed transit across the Oresund bridge - a rail and bus link - as now all travellers have to present their ID at checkpoints. And rail commuters have to change trains at Copenhagen Airport.

More than 160,000 asylum seekers arrived in Sweden in 2015, more per capita than any other country in Europe.

Sweden introduces border controls

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.