Migrant crisis: Why EU deal on refugees is difficult

- Published

Migrants have flocked to Budapest, Hungary, hoping to get to Germany by train

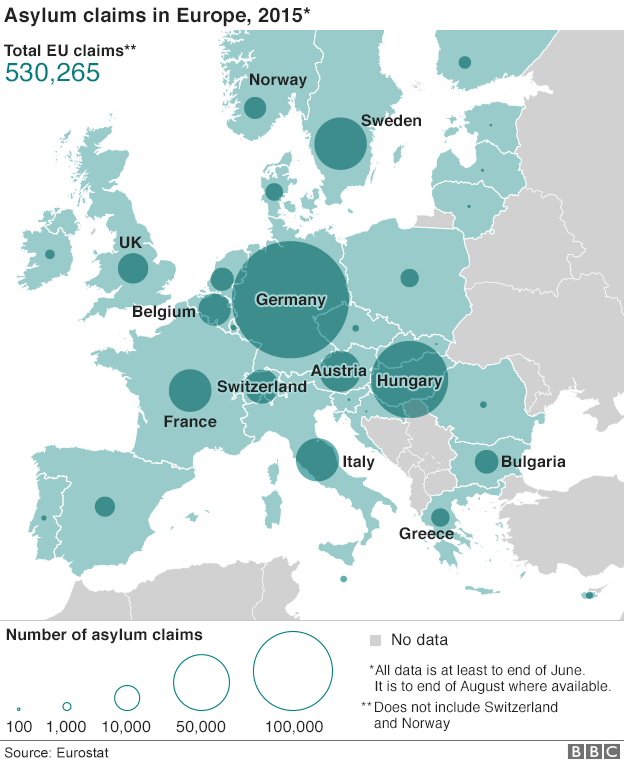

EU ministers have voted by a majority to relocate 120,000 refugees EU-wide, as this year's extraordinary influx via the Mediterranean and Balkans continues.

But for now the plan will only apply to 66,000. The other 54,000 will only be moved when governments decide where they should go.

In emergency talks the 28 EU interior and justice ministers argued over how to help Italy, Greece and Hungary, which lack the resources to register and house so many refugees and other migrants.

Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Romania voted against the plan, but they were overruled.

What is the plan?

The idea was to distribute 120,000 refugees over two years: 54,000 from Hungary; 50,400 from Greece and 15,600 from Italy.

But Hungary objects to being considered a "frontline" state in this crisis, and has rejected the relocation proposal. So Hungary's 54,000 will instead be transferred from Italy and Greece.

The 120,000 total corresponds to about 43% of all the refugees most in need who arrived in Italy and Greece in July and August, an EU statement said. , external

Despite Tuesday's vote, much uncertainty remains. Slovakia plans to take legal action against the decision.

Czech Interior Minister Milan Chovanec tweeted, external in dismay: "Very soon we'll realise that the emperor is naked. Today was a defeat for common sense! :("

The scheme will only apply to refugees most in need of international protection - not economic migrants. Vulnerable groups, including unaccompanied children and rape victims, get priority.

Only refugees from Syria, Iraq and Eritrea will qualify, because there is a threshold: at least 75% of refugees from those countries get international protection in the EU, according to official data., external

The European Commission proposed a mandatory distribution key, external - a mechanism that would oblige even reluctant EU member states to take in refugees. It would be based on several indices, including an EU state's total GDP, its total of asylum applicants and its unemployment rate.

But that automatic mechanism was dropped from the final agreement.

After initial screening and fingerprinting a refugee will be relocated to another EU country, which will get €6,000 (£4,337; $6,700) per refugee in EU aid towards their integration.

Consideration will be given to a refugee's language skills and family connections when deciding which country he/she goes to.

The European Parliament supports the plan.

What happens next?

The four "refusenik" countries can now argue that they were coerced into it by the EU, despite being ill-equipped to integrate refugees.

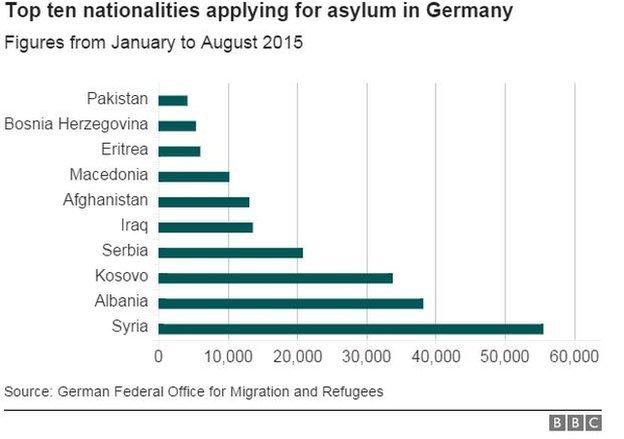

They argue that Germany is exerting a strong "pull", as the destination of choice for most refugees. Many of the refugees will still try to get there, they argue. It is easy to move around in the EU's Schengen passport-free travel zone, they say.

Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico said "as long as I am prime minister, mandatory quotas will not be implemented on Slovak territory".

The 22 September vote by qualified majority was highly unusual and contentious, because it directly affects national sovereignty. Traditionally each EU member state has its own rules concerning migrants from non-EU countries. The recognition rates for asylum seekers vary enormously across the EU.

There were hopes that the EU could have agreed by consensus, without having a divisive vote.

At least two other former communist states - Latvia and Poland - previously objected to mandatory quotas, but chose to vote with the majority.

Germany, France and Italy pushed hard to get mandatory quotas accepted.

Germany is currently taking in by far the largest number of non-EU asylum seekers - it expects at least 800,000 this year.

Despite much domestic opposition the German government says the influx is manageable, and the country - with its ageing population - will need more workers in future anyway.

Chancellor Angela Merkel sees helping refugees as a humanitarian duty, reminding EU partners that they signed up to such human rights standards by joining the EU.

But Germany is demanding EU "solidarity", saying its partners should take their fair share of refugees too.

The influx of migrants has created serious tensions between EU neighbours, notably since Hungary put up a razor-wire fence on its border with Serbia, criminalised illegal entry and tear-gassed migrants trying to get in.

Croatia has exchanged angry words with both Hungary and Serbia. Hungary is completing a razor-wire fence on its border with Croatia too.

Would all EU states take part?

No. Italy and Greece will not, because the idea is to ease their refugee burden. Hungary, which would have been exempt under the original plan, will now have to accept refugees.

The UK has opted out of this EU policy area. Denmark also has an opt-out, but said it would voluntarily take an extra 1,000 refugees.

Ireland has offered to accept 2,900 extra refugees, even though it also has an opt-out like the UK's.

The UK plans to resettle 20,000 Syrians over the next five years - Syrians currently housed in makeshift camps in the Middle East.

The EU also plans to set up "hotspots" around the Mediterranean, including in Turkey, Italy and Greece, to identify genuine refugees and prevent economic migrants entering the EU illegally.

Can the relocation plan really work?

There are serious doubts about this.

Legal wrangling might delay it, or even scupper it. The EU has an "emergency brake", external which could provide grounds for blocking the relocation, if a country feels its national security is affected.

However, the plan was drafted in line with Article 78(3) of the Lisbon Treaty, external, allowing for emergency measures to deal with a migrant influx.

In July the EU agreed to relocate 40,000 refugees - that is, Syrians and Eritreans currently in Greece and Italy. But they have not been relocated yet, some countries will only accept far fewer than 1,000, and so far the country totals have only been agreed for 32,256.

German police check: Europe is trying to crack down on people smugglers

The figure of a further 120,000 is dwarfed by the size of the problem. In January-July this year 438,000 refugees applied for asylum in the EU, compared with 571,000 for the whole of 2014.

Nearly half a million migrants have risked their lives, external crossing the Mediterranean to reach Europe this year. And about four million Syrian refugees are living in squalid camps in the Middle East, with no jobs - many of them longing for a new life in Europe.

The EU plan says host countries will have to warn migrants of the consequences if they try to move elsewhere in the EU. They can be deported if they enter another EU country illegally.

Faced with a right-wing, anti-immigration backlash across Europe, the EU has pledged to strengthen the bloc's external borders and do more to remove failed asylum seekers, as currently the deportation rate is below 40%.