Migrant crisis: How long can Merkel keep German doors open?

- Published

The chancellor's response to the crisis has won plaudits but some critics have questioned her emotional involvement

A few weeks ago, on the Austrian border, I asked a Syrian refugee why he wanted to start a new life in Germany.

Mohammed - a large man with sad eyes - looked up at the mountains behind him and then across the road bridge that connects Austria to Bavaria.

"It's Merkel," he said. "She says we're welcome."

The German chancellor's open-door policy on refugees has been one of the most emphatic of her chancellorship.

A few weeks ago, as tens of thousands of migrants waited at Hungary's Austrian border, Angela Merkel allowed to them to travel, unregistered, into Germany by temporarily suspending the Dublin protocol that requires asylum seekers to register in the first EU state they enter.

Global 'leadership'

Ostensibly, the decision was made to avert what Berlin feared would become a humanitarian crisis but the strategy is part of Mrs Merkel's much broader, welcoming stance towards asylum seekers.

It has won her widespread international admiration.

She was feted at the UN General Assembly in New York and U2 singer Bono congratulated her on 'the "kind of leadership we haven't seen on the global stage for a long, long time".

The German chancellor was feted at the UN this week for her handling of the migrant crisis

But it has also earned her notoriety among some of her European neighbours who blame her for exacerbating the flow of migrants into Europe.

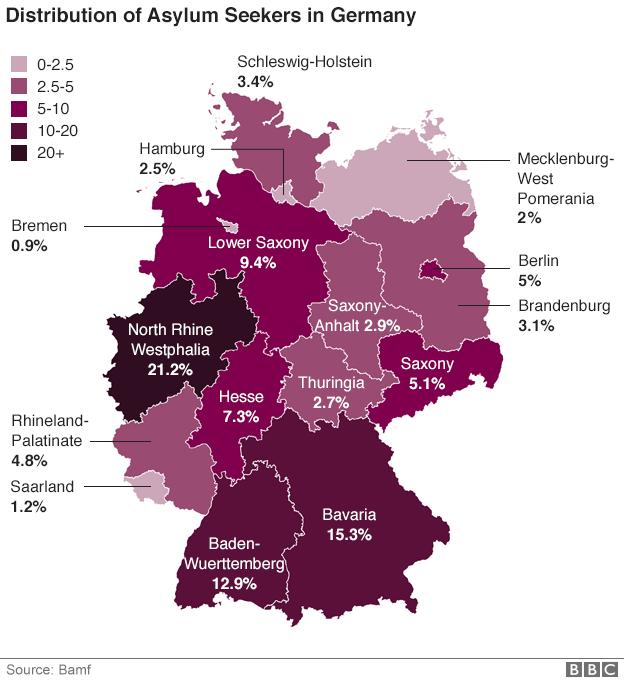

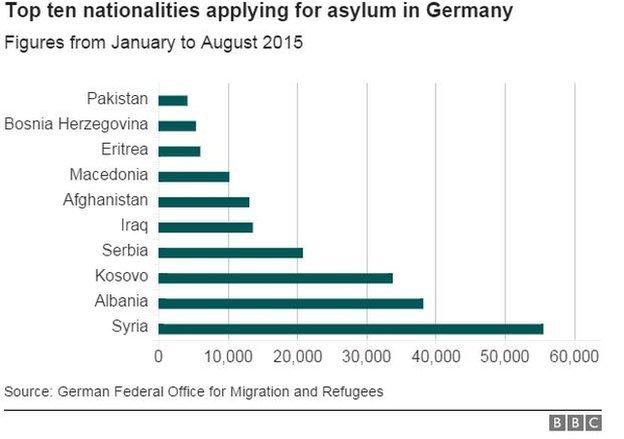

And it is beginning to cause concern at home in Germany, which now expects between 800,000 and one million people to claim asylum this year.

A growing number of political - and public - voices are starting to question both her motives for such a stance and her ability to control the consequences.

Migration crisis explained in maps and charts

A recent poll revealed that, since June, Mrs Merkel's approval rating had fallen five points to 63%.

Another survey suggests while half of all Germans approve of Mrs Merkel's refugee policy, 43% disagree with her stance.

'Uncomfortable truths'

And she's under pressure from within her own political ranks.

Horst Seehofer, leader of her Bavarian sister party the CSU, was the first to criticise, vociferously, her suspension of the Dublin protocol. Perhaps that's no surprise: since that moment late last month, he says 170,000 people have arrived in Bavaria to seek asylum.

The government hopes that new arrivals will be able to fill a skills gap created by Germany's ageing population

Klaus Peter Willsch, an MP from Mrs Merkel's Christian Democrat Union, recently told a newspaper "it's time for uncomfortable truths. There cannot just be feel-good language".

Even President Joachim Gauck appeared to strike a rather different tone in a speech at the weekend.

He said: "We want to help, we have big hearts. But our capability is limited."

Nevertheless, plenty of other MPs support the chancellor and she remains defiant.

"If Germany can't show a friendly face in an emergency situation, then it's not my country," she said. Such rhetoric is uncharacteristically emotional for the chancellor and it has not gone unnoticed among commentators.

'Driven by empathy'

Take a recent edition of Spiegel, which ran a front-page picture of the chancellor dressed as Mother Teresa. "Mother Angela," the headline proclaimed.

Germans long knew their chancellor as a rational, deliberate, decision-maker, the accompanying article read, but in the refugee crisis a new Merkel had emerged "driven by empathy".

And that's why Hans-Joachim Maaz - one of Germany's leading psychiatrists - believes Chancellor Merkel is out of her depth.

"She's taking a mother role - and that to an extent protects her from criticism," he says.

"It's also a role she strives for. The fact she's taking selfies with refugees shows there's a lack of distance - a distance that a politician should maintain."

Ultimately it may be some years before the results of her strategy can be truly assessed.

Germany's population is ageing fast and the government's hope is that the new arrivals can fill a desperate skills gap.

Of course, as many here point out, that all relies on successful integration, which takes time. And, with no real long-term solution to the refugee crisis in sight, concern over the feasibility of Germany's position will only continue to grow.

Angela Merkel promises Germans that "we will manage" ("wir schaffen es"). And she has sought to reassure Germans by introducing a tough new asylum law. If it is passed by parliament, cash handouts for asylum seekers will be scrapped.

I put her message to one rather harassed-looking man in charge of a busy reception centre for arriving refugees in the south of Germany.

"Mrs Merkel says we will manage," he replied, "but it's people like me who have to make it happen."