Migrant crisis: EU leaders avoid punch-up but fail refugee test

- Published

- comments

Record numbers of migrants and refugees are reaching Hungary and neighbouring Austria is struggling to cope

There is a real morning-after feeling in Brussels.

All over Europe, refugees and other migrants continue to pour over the borders.

Hungary declared a new record of more than 10,000 people arriving in one 24-hour period.

Austrian officials say they are swamped by asylum applications. There are calls for a parliamentary debate on "Austria in a State of Emergency".

So what progress - if any - did EU leaders make at their summit in Brussels on Wednesday night?

That depends on what you believe the true aims were of the official host, European Council President Donald Tusk, and the de facto shepherdess of the meeting, German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Did they solve Europe's migrant crisis in an evening? No.

Did they cool frayed tempers and focus minds? Yes.

Is that enough? Clearly not.

Is it in any way significant? It is.

EU summit official statement, external

How is crisis dividing EU countries?

Has Merkel's strategy played into hands of French far right?

'Play nice'

As Mr Tusk publicly pointed out, Europe has lost control of its external borders and millions, not thousands, of refugees and others in search of a better life are interested in crossing them.

Katya Adler: ''The divisions are very real over sharing the number of asylum seekers more equally''

Nothing can be achieved while EU prime ministers and heads of state exchange insults, threats and unilaterally slam national borders shut.

Breaking bread, sitting down for a meal together, is a time-honoured way for feuding family members to put their differences aside - for a moment at least - and remember that they are supposed to be united.

The whispered pre-summit instruction in everyone's ear had been, "Play nice!"

And certainly the tone, in front of the cameras at least, was markedly more conciliatory when EU leaders arrived for their "informal dinner".

Mrs Merkel said a first step had been taken but a permanent quota system for receiving refugees was necessary

UK Prime Minister David Cameron spoke of a comprehensive approach; Viktor Orban, the normally fiery Hungarian leader told me everyone had to co-operate and Angela Merkel insisted, "What we cannot say is Europe cannot deal with this. I say it again and again, we WILL do this!"

EU leaders do actually agree on a number of key issues:

Cracking down on people smuggling rings

Getting asylum claims processed faster, so failed claimants can be deported more rapidly

The need to secure Europe's external borders

Boosting aid to the sprawling, squalid refugee camps around Syria, so fewer people feel tempted to come to Europe

Stepping up attempts to try to end the war in Syria

But common resolve is one thing. Effective, immediate action is quite another.

And some of the leaders' goals are more realistic than others.

At a press conference after the summit, the German chancellor spoke of the need to talk to Syria's President Bashar al-Assad as part of a new European push for peace in his country.

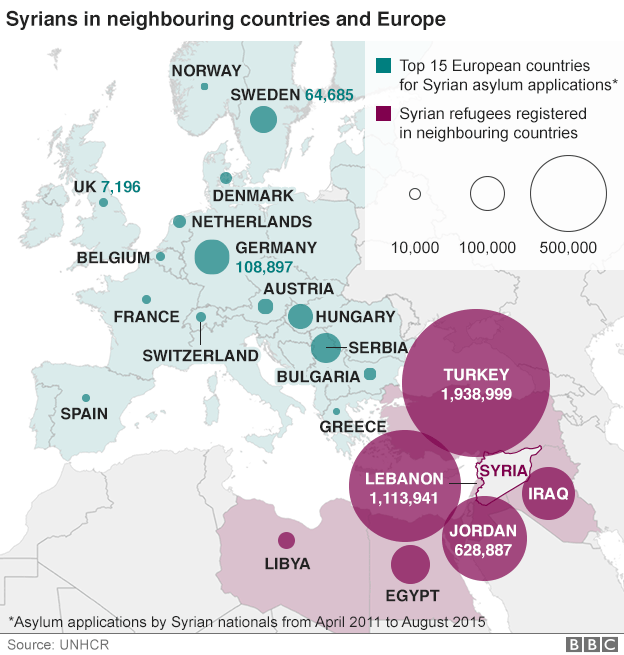

The conflict has now reached Europe, and Germany in particular. It is the European country of choice for Syrian refugees.

In the past, Germany has joined other Western leaders in calling for President Assad to step aside. So these talks would be delicate and controversial, they will not happen overnight and their chances of success are limited, to say the least.

Then there's the question of building what is often dubbed Fortress Europe - or what Donald Tusk described last night as "closing Europe's doors and windows".

In other words, stopping the mass flow of refugees and other migrants in to Europe.

Throwing aid money at refugee camps in the Middle East is unlikely to stop people coming.

It is not, in the end, a question of better food and blankets.

Syrian refugees yearn for the safety and security they believe Europe provides. That is why so many risk their and their children's lives to get here.

Courting Turkey

Turkey is the main departure point for Syrians trying to move to Germany and EU leaders agreed last night that better relations with Ankara was key.

The UK prime minister called for more to be done to stabilise the regions where the refugees came from

Currently, ties between Turkey and the EU are strained.

Amongst other things, Turkey tried desperately to woo the EU for years in the hope of joining the club, only to be repeatedly rebuffed.

Now, courting the Turkish government and persuading it to clamp down on migrants heading for Europe is likely to be complicated and costly. And not just in terms of money.

For a start, Turkey wants EU and US support for a buffer and no-fly zone in northern Syria by the Turkish border.

Frontier agency

Better securing Europe's own borders is another vexed question.

As a stopgap measure Hungary has angered many of its European partners by building razor wire fences and legalising the use of rubber bullets, tear gas and imprisonment to deter migrants.

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker is looking at forming a pan-European frontier agency, but that would mean countries like Italy and Greece losing national sovereignty over their borders, effectively handing them over to Brussels.

They are not overly keen on that idea.

EU ministers forced through a quota for member states to accept refugees, against the wishes of four countries

Greece is already smarting from the terms of its financial bailout agreement, policed by Brussels.

Despite honourable intentions, in terms of taking action to make an immediate difference on the ground, last night's summit was a miserable failure.

In the anxiousness to avoid a punch-up there was also one screaming omission from the leaders' debate: what to do with the spiralling number of refugees and other migrants already in Europe?

The avoidance of the topic was all the more glaring as the summit came hot on the heels of EU interior ministers forcing through a quota system for 120,000 asylum seekers, despite angry protests from Central and Eastern European countries.

Its idea of a permanent quota system, with numbers automatically divided more equally across the continent, remains deeply unpopular in many countries.

But Europe cannot hide from the issue. Unaddressed, it will test relations between EU countries to breaking point.