Svetlana Alexievich: Exposing stark Soviet realities

- Published

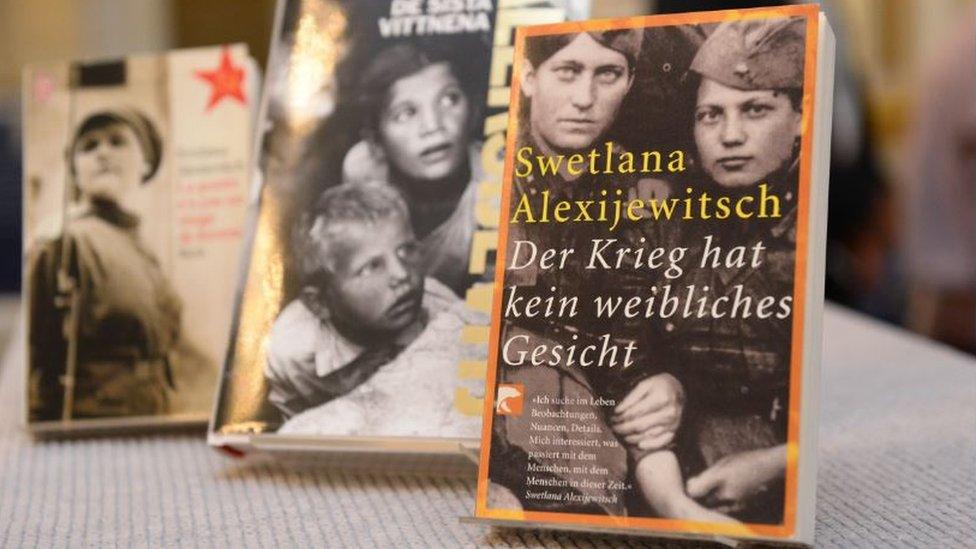

The judges called Alexievich's books "a monument to suffering and courage"

Svetlana Alexievich - this year's Nobel laureate for literature - says her approach is to let "human voices speak for themselves".

She first came to prominence in 1985 when, as a 37-year-old journalist in the Soviet Union, she published her first documentary book: War's Unwomanly Face.

It is an oral history of ordinary Belarusian women who fought in World War Two.

Belarus was still very much in the grip of communist officialdom, intensified by the pomposity of celebrations to mark the 40th anniversary of the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany. The tone of her book - poignant, human, touching - came as a complete shock.

That book defined her style for years to come.

Fortunately her success coincided with the refreshing, revolutionising effect of Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms in the late 1980s. The then Soviet leader promoted "glasnost" (openness) and "perestroika" (restructuring).

Strong competition

Alexievich had been mentioned as a possible Nobel laureate for years, even though internationally she is much less known than competitors such as Philip Roth, Joyce Carol Oates and Haruki Murakami.

Yet the announcement was unexpected and unusual. She is the 14th woman to have got the award, but more importantly she works in a non-fiction genre, which emerged from her work as a journalist.

Traditionally the Nobel Literature Prize has celebrated artistic endeavour - purely literary or "ideal" values, as Alfred Nobel intended.

The only other non-fiction writers awarded the prize were Winston Churchill and Bertrand Russell. Even Alexander Solzhenitsyn won it as much, if not more, for his fiction.

Alexievich documented some of the Soviet Union's darkest episodes

Her books also won her the Swedish PEN prize

After War's Unwomanly Face she tackled themes that were taboo in the Soviet period. Zinky Boys (1989) was about the savage war in Afghanistan, and Voices from Chernobyl (1997) was about the 1986 nuclear disaster in Ukraine. The books were translated and turned her into a symbol of changing political realities in the former USSR.

She remained true to her documentary style, and it was that multitude of voices that persuaded the Nobel Committee to honour her "polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time".

Belarusian and Russian reaction to Alexievich prize

"A new national leader has appeared in Belarus, She has more authority now than any politician - the president or a minister. And she's someone with normal European values" Belarusian playwright and screenwriter Andrey Kureychyk

"It will go down in the history of the development of the Belarusian nation, society and state" Belarus foreign ministry

"Alas, she was given the prize for her hatred towards Russia" Pro-Kremlin Russian journalist Dmitry Smirnov

"She represents the Russian world without Putin: the world of Russian language and literature, which opposes the Russian government. The Nobel prize has given us a spiritual leader" Independent Russian journalist Oleg Kashin speaking on Ekho Moskvy radio

Alexievich in her own words

"Life is beautiful, but too short, dammit"

"The fairest thing in this world is death - no one has ever managed to buy himself out of it"

"We have always lived in horror, we know how to live in horror, horror is our habitat - in this our people are unequalled"

"Communism is like prohibition: good idea, but doesn't work"

"Everybody likes to talk, but they cannot hear each other"

"I know everything about people, much more than I ever wished to know."

Despite her fame in post-Soviet Russia and abroad, Alexievich inevitably fell out with the authoritarian regime of Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko.

A political dissident and opponent of the regime, she left her homeland in 2000, moved to Germany and France, and returned to Minsk only in 2011.

Political dissident

She has no illusions about the nature of political power in post-Soviet countries.

"I love the Russian world, but the kind, humane Russian world," she added, talking of Russia under President Vladimir Putin.

"I do not love Beria, Stalin, Putin... how low they let Russia sink," she said - reflecting on Mr Putin's ruthless Soviet predecessors.

"Dictator Putin and dictator Lukashenko both have mandates from their societies, they are the concentrated desire of the people, which means that society is at that particular stage in its development," she said during the launch of her latest book, Second-hand Time.

So her Nobel success is a bit awkward not only for Mr Lukashenko but also for Mr Putin.

It is an enormous honour for the small Belarus nation, which has never been anywhere near such international literary recognition before.

She is only the sixth Russian-language writer to win the world's top literary prize - after Ivan Bunin, Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Sholokhov, Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Brodsky.

- Published8 October 2015

- Published9 October 2014

- Published3 March 2015

- Published6 June 2014