Flight MH17: Russia and its changing story

- Published

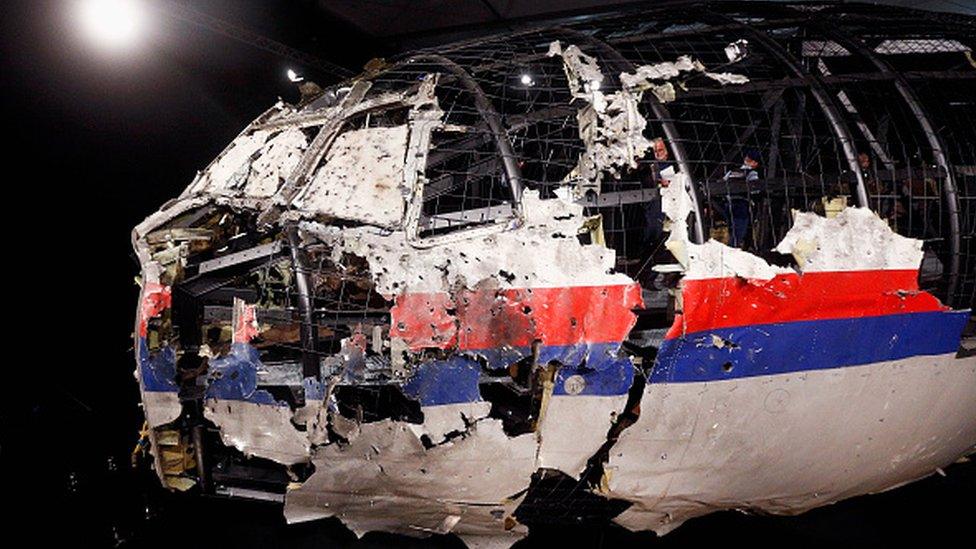

Investigators presented the wrecked cockpit of flight MH17 when they made public their findings

When a Dutch team revealed this week what caused the Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 air disaster in eastern Ukraine, their inquiry steered clear of saying who fired the missile that brought the plane down, killing all 298 people on board.

But Russian officials immediately complained the inquiry was biased, keen to absolve the Moscow government of any blame.

And deep within the report, months of disagreement are revealed between the Russians and the Dutch Safety Board (DSB) in what soon resembles a blame game.

Under the rules of international crash investigations, the DSB has no authority to apportion blame, although board chairman Tjibbe Joustra said later that pro-Russian rebels had been in charge of the area from where the fateful missile was fired.

For months, Russian experts directly challenged the DSB's findings, and all the while the Russian arguments constantly appeared to change.

It was like a high-stakes game of chess: one side waiting for the other to move, then analysing it and trying to hit back with a counter argument.

Russian BUK missile maker Almaz-Antey rejected the Dutch findings on the MH17 crash

Read more

Key findings: Dutch Safety Board report in a nutshell

Malaysia plane crash: What we know: How flight MH17 unfolded

A reporter's story: Searching for truth at the crash site

Remembering the victims: Shared sadness and sunflowers

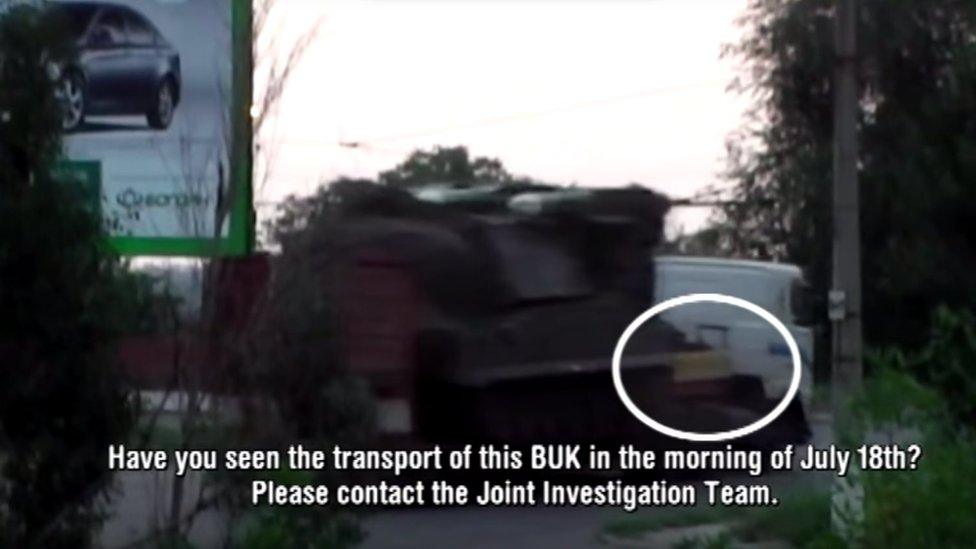

Ukraine's government and several Western officials have said the missile was transported into a rebel-held area from Russia. The Dutch-led criminal investigation has already published photos of the launcher being moved around rebel areas.

But Moscow has always denied having anything to do with the tragedy.

International investigators have already made an appeal using photos of a BUK launcher in a rebel-held area

A few days after the air crash Russia's Ministry of Defence suggested the Boeing 777 was downed by an air-to-air missile. It said Russian radar had spotted a Ukrainian fighter jet 3-5km (2-3 miles) away from the plane.

In July 2015, Russia's investigative committee repeated the allegation, saying the missile "was not produced in Russia". And this version was widely promoted by Russian state TV, with one channel even showing an experiment involving a fighter jet firing on an old plane.

But then the story switched, and Russian missile company Almaz-Antey blew up another plane to prove MH17 had been downed by a BUK surface-to-air missile.

In another apparent chess move, Moscow was now arguing that MH17 was brought down by a rocket launched from Ukrainian government-held territory, although it acknowledged it was missile made by Almaz-Antey.

Blast location

As the Dutch Safety Board prepared its report, several meetings were held with Russian specialists, who analysed the information they were given and at their last joint meeting questioned the Dutch findings. The Russian team put forward three arguments:

The blast location for the warhead was closer to the plane than the DSB said

MH17 must have been hit by a different, older type of BUK missile

The BUK missile must have been launched from a different area

It was time for the Dutch to respond. And, in the very final pages of the report (p94),, external they do.

First, the DSB says the Russians had relied on an inappropriate method to decide exactly where the warhead exploded.

The inquiry team used a "stringing method" to determine the trajectory of the missile parts that hit the plane. Specialists used three-dimensional scans and fibreglass rods and then set up a network of lines of string.

While this helped explain the general direction that fragments inside the warhead hit the plane, the Dutch insisted it could not determine exactly where the warhead blew up because that trajectory changed dramatically after impact.

The Dutch argued the "stringing method" could not be used to decide the exact location of the missile blast

Although the Russians did consider the impact inside the fuselage, the DSB pointed out that the fragments of the warhead that penetrated the plane changed direction and ricocheted.

Detonation point

The two sides' difference of opinion on where the warhead exploded is key to their disagreement on other findings.

An animated video from the Dutch Safety Board shows the damage to the plane and how it was caused

Because the Russian detonation point is closer to the plane, their experts came to a different conclusion about the type of warhead, and the number and weight of destructive fragments inside it.

Almaz-Antey, which produces the BUK launcher and anti-aircraft missiles, and the Ukraine Research Institute were both asked by the DSB to calculate the path of the rocket.

The Russian specialists worked out a wide area to the south and south-east of the town of Snizhne. The Ukrainians determined a significantly smaller area but within the area identified by the Russians.

Based on that, the Dutch Safety Board calculated a large area from which the missile may have been launched. It is almost twice the size of the area calculated by the Russians.

However, after the Russians presented their findings to the DSB, they used their own simulation to argue that the missile must have been launched further west, from Zaroshchenske, which was at the time in Ukrainian-controlled territory.

This village lies some 20km (12 miles) away from the area that Almaz-Antey first suggested the DSB.

It was, apparently, another Russian move in this weird, chess-like investigation.

At odds

Almaz-Antey has now accused the DSB, external of misinterpreting the Russian calculations in an "impressive example of dishonest use of our documents".

Its specialists insist the missile launch area mapped out in the report had never been submitted to the Dutch, and in any case the original Russian calculations were based on "faulty conditions" provided by the DSB.

The two sides are now completely at odds.

The Dutch say that the Russians have simply got it wrong, basing their "calculations on an incorrect detonation point and orientation of the weapon resulting in an incorrect missile trajectory".

This game of chess is far from over and the stakes are rising. The international criminal investigation will be published in 2016, and that will apportion blame.