Athletics doping: Russian athletes fear ban from Olympics

- Published

A World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) commission report has recommended that Russia should be banned from from next year's Olympics

Being labelled cheats is bad enough, but for Russian athletes and politicians a ban from the next Olympics would be devastating.

And that's the fear here.

The initial reaction to claims of widespread doping and corruption in sport was predictable: a burst of outrage, painting the entire scandal as a "political" attack.

Sport became the latest battlefield in the "war" between East and West.

Denying accusations

But the tone has since shifted as the need for damage limitation has sunk in.

Late on Wednesday night, President Putin made his first comments on the topic, and they were conciliatory.

"I agree that this is not only a Russian problem," he told sports officials gathered in Sochi. "But if our international colleagues have questions, we must resolve them."

President Putin said the country needs to resolve doping questions

A judo black belt himself, Mr Putin stressed that sport is only "attractive" when it's a fair fight.

"We in Russia must do everything to get rid of this problem," he instructed his audience.

Sports Minister Vitaly Mutko had already admitted to a problem, pointing out that Russia disqualifies up to 300 athletes each year for doping.

Even so, officials deny the kind of "systemic" and "state-sponsored" cheating described in the Wada investigation.

Considering the seriousness of the allegations, the head of Russia's anti-doping agency (Rusada) has been particularly dismissive.

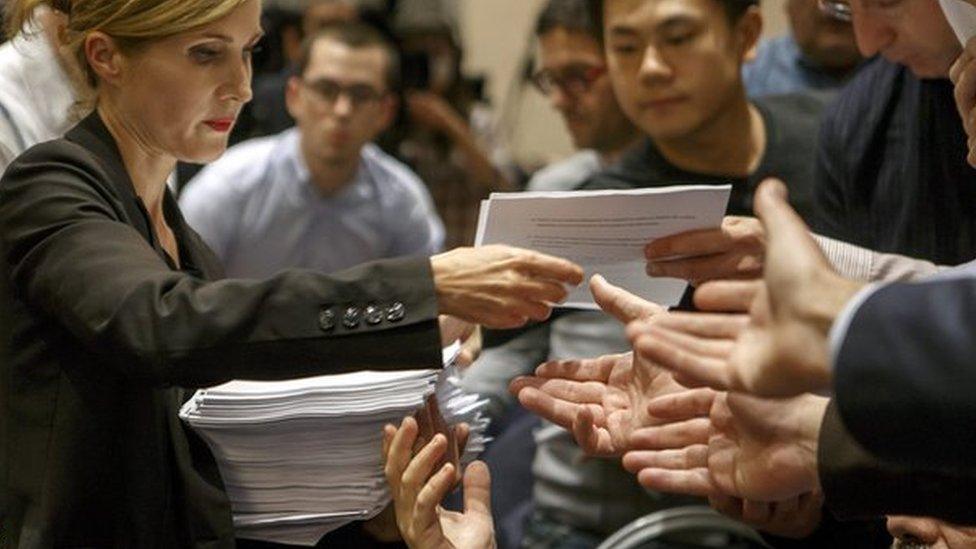

"The accusations against Rusada are based on personal testimony," a relaxed-looking Nikita Kamaev told journalists crammed into a room at the agency's headquarters this week.

Mr Kamaev denied that Russian athletes were pre-warned of testing

"When you have an athlete who's been disqualified for cheating and their word is worth more than ours - that raises questions," he argued, apparently unfazed by all the secret recordings provided as evidence by those whistleblowers.

Mr Kamaev denied that Russian athletes were pre-warned of testing and laughed off claims of involvement by the state security service, the FSB.

As for the laboratory at the heart of the corruption claims, staff have not answered calls since the director resigned on Tuesday.

'Our sport is sick'

As Russia formulates its official response to Wada - to submit on Thursday - state television coverage has gone remarkably quiet.

There's been little of the usual nationalistic drum-banging on social media either and the whole scandal has been confined largely to the sports pages of newspapers.

A rare Russian front page story on the doping scandal

What comment there is, suggests concern rather than patriotic bluster.

"Sadly our sport is sick," Komsomolskaya Pravda confessed today.

"We need to punish our own athletes [for doping], regardless of their achievements," the paper suggests. "But for now, sadly, any attack from outside will hit its target because there is something to hit."

Soviet sport was all about proving the superiority of a superpower - whatever the cost - and in those days, state-managed drug-enhanced performance was the norm.

The Wada report shows that system didn't collapse with the USSR, as one-time athletes became trainers and managers.

Timeline: Athletics doping accusations

December 2014: German documentary alleges Russian doping scandal

February 2015: IAAF's Diack says athletics faces 'crisis'

August 2015: Coe says IAAF will react robustly

August 2015: Wada 'alarmed' by fresh allegations

"It's widely believed that doping is part of elite sports," argues Russian-born Sergei Ilyukov, now a doctor with the Finnish Olympic team.

"You can build the perfect anti-doping system, but if the mentality doesn't change it will be ineffective."

As Russian sport is still largely state-driven and funded, Mr Ilyukov argues athletes are pushed harder for results.

Problem 'runs deep'

At the Athletics Federation (Araf) though, acting boss Vadim Zelichyonok described the allegations as "painful" and told the BBC they were a "stain" on Russian sport that would be hard to wash off.

But he also called some of the claims so old they "smell of mothballs", arguing that Russia began cleaning up its own act some time ago.

While acknowledging problems, Mr Zelichyonok is adamant that there is no corruption in the Athletics Federation

Mr Zelichyonok points out a management shake-up at Araf: his own predecessor resigned last February after a quarter of a century at the helm, and there's a new chief trainer.

One of the five athletes Wada wants banned for life - Olympic champion Maria Savinova - is on maternity leave. But Ekaterina Poistogova and Ksenia Ugarova were both suspended soon after claims of cheating emerged.

The status of the remaining two women is unclear.

"Not one of us [the new team] has ever given any athlete or trainer a carte blanche to use banned substances," Vadim Zelichyonok insisted this week. "We say consistently that doping is a dead-end. That the time of using banned substances is over. Some listen, but sadly far from all."

He admitted that the problem runs deep, with even youth sport affected. And the Federation is still tackling serious doping problems at Russia's national race-walking base in Saransk.

But Mr Zelichyonok was adamant about one thing.

"Now, there is no corruption. I can put my hand on the bible to that," he said.

Russian athletes are used to pride of place on the podium at the Olympics

With Russia's place at next summer's Olympics at stake, President Putin has now led the way in urging the decision makers not to penalise "clean" athletes for others' mistakes.

"Responsibility must be personalised, that's the rule," Mr Putin argued.

If his appeal is heard, Russia's claim of zero tolerance on doping will be put to the test.

Used to pride of place on the podium, Russian athletes could well put on a poorer show if they make it to Rio. The question is whether that's a price they're ready to pay.

- Attribution

- Published10 November 2015

- Attribution

- Published9 November 2015

- Attribution

- Published16 February 2015

- Attribution

- Published9 November 2015

- Attribution

- Published7 November 2015

- Published9 November 2015