Paris attacks: Is Molenbeek a haven for Belgian jihadis?

- Published

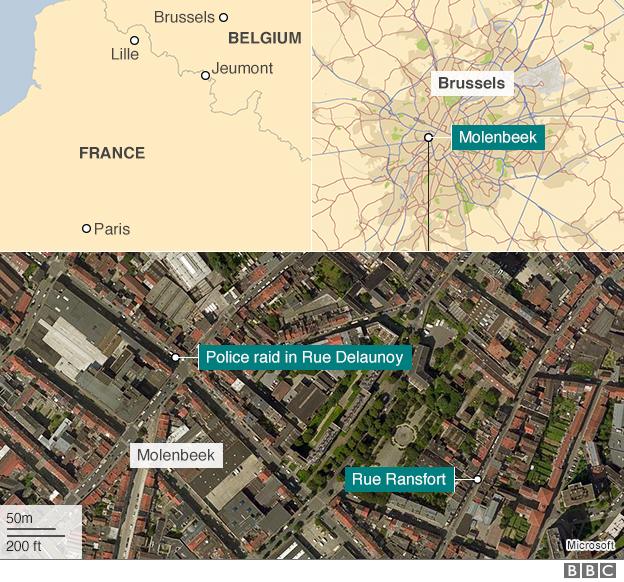

Police arrested 23 people during raids on Molenbeek after the attacks in Paris

About three miles to the west of Brussels' Grand Place there's a neighbourhood far removed from the chocolate shops and cafes so synonymous with the city's tourist centre.

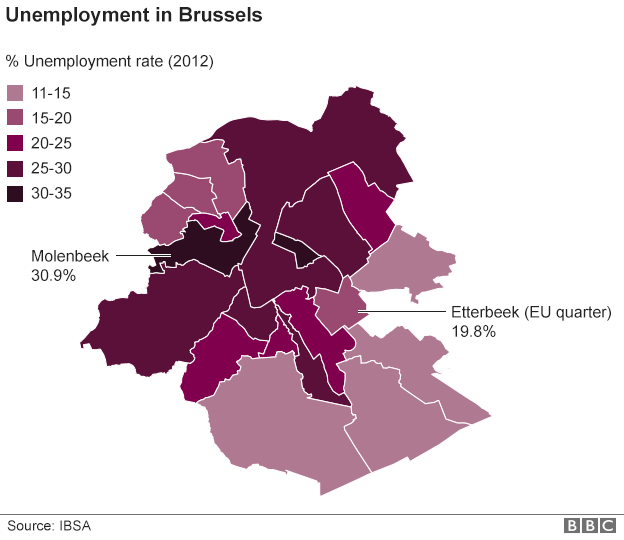

Molenbeek-Saint-Jean is a densely-packed district where unemployment is high and disengagement rife. Children play on green open spaces framed by graffitied walls, and behind the colourful shop facades there are pockets of poverty.

The population is transient, but some families have settled; mothers with buggies are a familiar sight. Within its melting pot of cultures there's a large Muslim community.

The recent Paris attacks have thrust Molenbeek into the international spotlight. Belgian authorities carried out a series of raids searching for key suspects believed to have lived in the area. Two people arrested have been charged with terrorist offences.

It's led to Molenbeek being widely labelled as a jihadi haven, but for some residents that's an unfair description.

Restaurant owner Derdabi Nabil said his regular customers came from more than 30 different countries but live in harmony in this corner of Brussels.

He was working on the day of the first police raids in connection with the Paris attacks.

"There were lots of police and lots of weapons," he said. "It was the first time we've seen anything like that.

"There is not usually any problem here. There is no problem here."

But Molenbeek has a history of connections with cases of extremism. It was searched as part of anti-terror operations that were carried out in Belgium in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks.

A suspect in a thwarted attack on a high-speed train from Belgium to France was reported to have stayed at his sister's house in Molenbeek, and a Frenchman accused of shooting dead four people last year at the Jewish Museum in Brussels also spent time in the area, according to Reuters news agency.

"Molenbeek is a strange part of the town," Brussels-based intelligence expert Claude Moniquet said.

"It has a very mixed population with thousands of immigrants, approximately half are of Muslim descent and in some parts 70-80%.

"That means no mixing population and the possibility of a place to hide for terrorists."

The crackdown in Molenbeek follows multiple attacks on bars, restaurants, a concert hall and a stadium in Paris on Friday

Some argue that Molenbeek has fallen between the cracks of long-term political divisions that dominate Brussels.

Belgium's Interior Minister Jan Jambon admitted a high proportion of those who have left Belgium to join Islamist groups came from the area, and recently vowed to "clean it up".

"The number of people going to Syria has gone down," he said. "But those who go, still come from Molenbeek and Brussels."

But some are angered by labels like "hotbed of extremism" which they see as an exaggeration.

For many, Molenbeek is home despite its problems, and they don't want the actions of a few to permanently taint an entire community.