Europe migrant crisis: EU battles to keep Schengen freedom

- Published

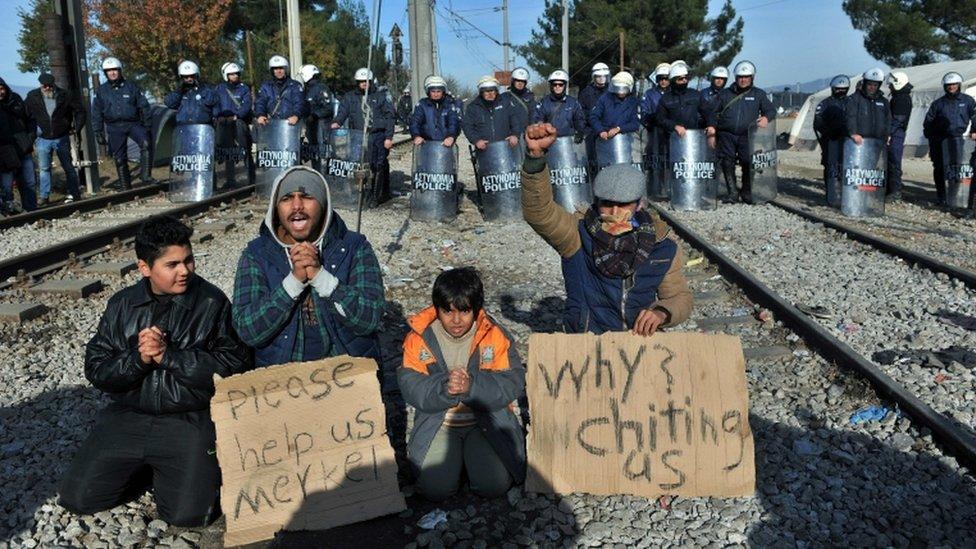

The migrant crisis has brought renewed scrutiny to the way European borders are policed

Two pressing issues - migration and the fight against terrorism - are set to dominate the EU summit, as leaders gather in Brussels.

But the chairman, European Council President Donald Tusk, will keep the two discussions separate - despite concern that some jihadists are slipping into the EU posing as migrants and exploiting the freedom of movement provided by the Schengen zone.

At least two of the killers involved in the Paris attacks got in among the crowds of migrants arriving daily on the Greek islands near Turkey.

But EU leaders are anxious to avoid sounding like the nationalists who argue that the removal of border controls in the EU left Europeans more at risk from terrorists. That is the rallying cry of the French National Front (FN) and some other populist parties.

Migration and terrorism are also treated as separate issues because - as pointed out by EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker - many asylum-seekers are themselves fleeing from the terror inflicted by Islamic State (IS), the Taliban and other extremist groups.

Borderless Europe

The dilemma for the EU is that Schengen - the passport-free area embracing 26 countries - greatly eases the flow of people and goods across the EU, but also requires more information-sharing, to prevent cross-border criminality.

About 1.7 million EU citizens cross borders daily in the Schengen zone to go to work, the Bruegel think-tank reports.

And opinion polls indicate that many Europeans value Schengen more than any other change brought about by the EU.

But temporary border controls have been reimposed - by France, Germany, Austria and Hungary.

So the stakes are high at this summit.

"Our goal is clear: we must regain control over our external borders to stem migratory flows and to preserve Schengen," said Mr Tusk in his summit invitation letter, external.

Mr Juncker said Europeans now have "one border" and "a shared responsibility to protect it".

"We want to defend everything Schengen represents, and let me tell you that Schengen is here to stay," he told the European Parliament, external.

Police checks

Saving Schengen means beefing up the surveillance of all people entering or leaving the Schengen area.

So in future EU citizens, as well as those from outside the bloc, will have their passports checked against police databases.

There is much work to do, however, to link up and improve those databases.

More than a million refugees and other migrants have surged into the EU this year, most of them desperate to reach Germany or other northern countries where job prospects are better, or where relatives can help them settle.

The Syrian war has pushed irregular migration to the EU to a record high.

There are fears that the international campaign to smash IS, and the Russian bombing in support of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's forces, will drive even more Syrians to flee abroad.

So the 28 leaders in Brussels will look again at the EU's help for Greece and Turkey. The migrant registration process is still slow and patchy.

Turkey, struggling with more than two million Syrian refugees, now has much bargaining power. Critics say the EU risks compromising its human rights standards as it leans on Turkey to curb the migrant flow.

New force

Frontex - EU's border force explained

Greek coastguards and the EU's Frontex border agency only manage to intercept 20% of the migrants who reach Greek islands after life-threatening voyages, according to Frontex.

This week the Commission unveiled an ambitious plan, external for a new EU Border and Coast Guard to tackle problems on the EU's external borders.

The force - stronger than Frontex - would have 1,000 permanent staff and 1,500 reserves, who could be deployed rapidly to a trouble spot, within three days.

That could happen even without the host country requesting it - if the rest of the EU decides to take action.

Such force majeure might be the exception - but Poland has already raised objections on sovereignty grounds.

Once again, the migrant crisis is threatening to divide, more than unite, Europe.