Will France's new wine regions threaten Champagne tradition?

- Published

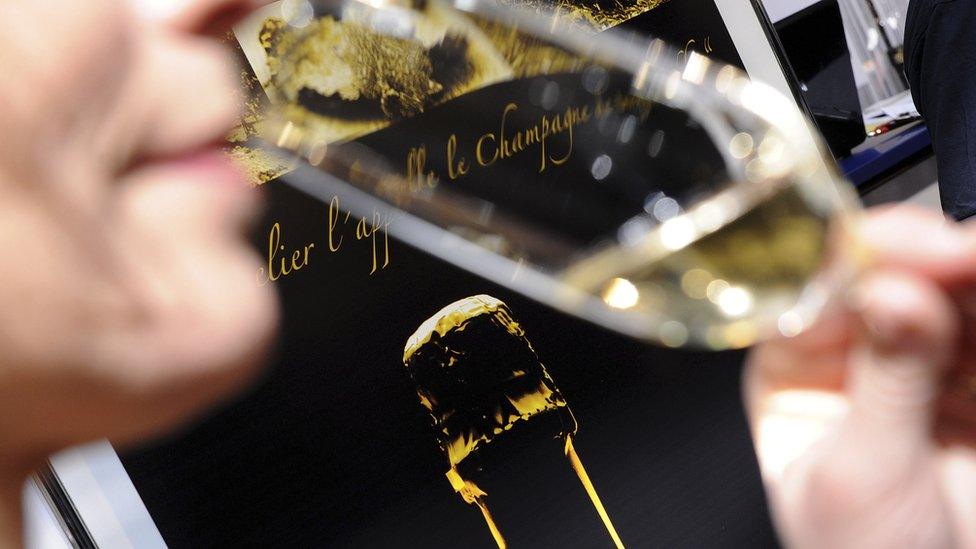

The traditional French notion of terroir holds that good wines are the result of earth minerals, climate and human know-how that are specific to a particular place

A mini-liberalisation of the French wine sector is raising fears among some traditional growers that their protected vintages will be lost in a sea of homogenised plonk.

Champagne producers are among the most vociferous opponents of a rule that comes into force on New Year's Day, and which should open up new French wine regions for the first time in nearly a century.

Like all rules governing EU agriculture, the new regulation comes from Brussels - but eight years of tough negotiations have removed some of its original bite.

The idea, when first announced in 2008, was for a more or less complete liberalisation of the sector. Anyone wanting to plant a vine and sell the resulting produce would be allowed to do so.

But such was the outrage - in France and elsewhere - about the damage this might do, the scope of the directive has been considerably reduced.

Still, in its way it does mark something of a revolution.

As of 1 January, the rules on planting new vines in the EU are changing in a fundamental way.

Champagne producers have been among the most vociferous opponents of the new rules

Up till now - in order to protect existing growers - the basic premise was that all new vineyards were prohibited, and special dispensation was required in order to plant.

Now the reverse applies. Now vine-planting is assumed to be legal - unless a good reason can be found to stop it.

Reputation

In France the change is accompanied by an agreement that any increase in the number of vines will be limited to 1% a year - that is around 8,000 hectares.

But, significantly, these new vines can be anywhere in the country. And they can be for the production of a new wine "appellation" or label - to be called VSIG (Vins sans Indication Geographique: Wines without Geographic Indication).

Until now, wine producers have been restricted by existing geographical indications

Many in the wine business have welcomed the change because they think it will bring in new ideas and foster the development of new brands for the international market.

But opponents fear it is a foot in the door for low-quality producers, who will end up tainting the reputation of the business as a whole.

In the Champagne area around Reims, some growers say it will mean vines being planted on unsuitable land - with no respect for the traditional French notion of "terroir".

Terroir is the principle that justifies the protection of large parts of French agriculture. It is the idea that good wines and foods are the result of a combination of earth minerals, climate and human know-how that are specific to particular places.

"This rule spells the death of the Appellation d'Origine Controlee (AOC) system which we have had since 1927," said Pascal Perrot, mayor of the Champagne village of Vertus.

"There will no longer be any criteria for planting. Terroir, the quality of the earth, exposure to the sun - they will count for nothing. Anyone will be be able to make pseudo-champagne, either here or anywhere else."

Threat to image

Most people who follow the wine industry believe these fears are excessive. For one thing traditional wine areas like Champagne will continue to have strict control over the planting of new vines.

And the government has said it will keep a close watch to ensure new vineyards do not damage the reputation of existing vintages.

Indeed a number of villages in the department of Aisne - which abuts the Champagne region - have already seen their application to grow vines turned down by Paris, on the grounds that they might pose a threat to the image of their mighty neighbour.

This has exasperated the people of Acy - one of the villages - who point out that until the 1920s and 30s, when France's wine map was formally delineated, they themselves were reputed wine-growers.

But for other ambitious wine entrepreneurs the new directive is hugely welcome.

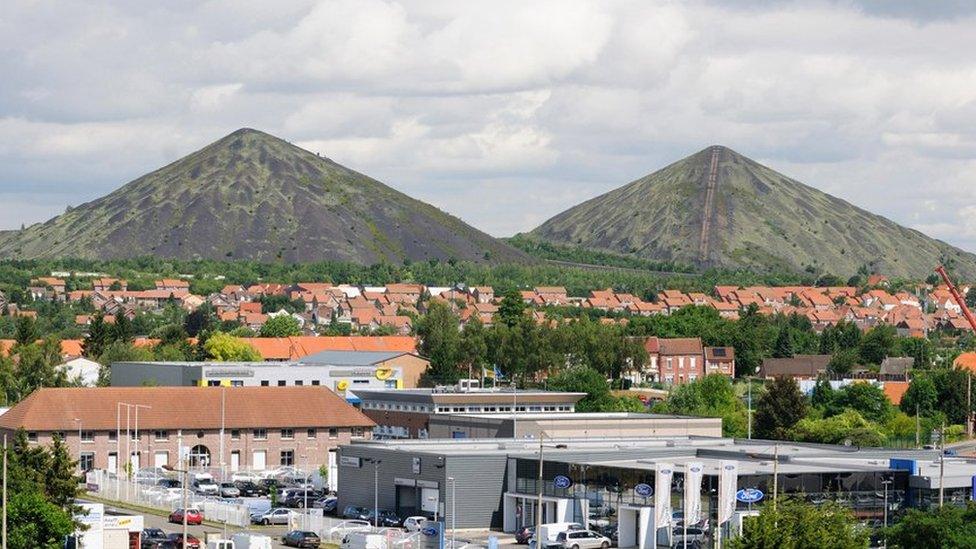

Henri Jammet grows grapes on a slag-heap in France's most northerly vineyard

In the past, wine was produced in the Paris area, and with a warming climate there is no reason why vines cannot be planted right up to the border with Belgium.

Indeed one vineyard already exists, just a few miles from Calais. It was planted a few years ago on the side of one of the region's famous "terrils" - or slag-heaps from the mining industry.

Local enthusiasts guessed that the slope, the drainage and the southerly aspect were all ideal - and they were right. The vineyard makes a decent chardonnay, which is known as Charbonnay (a play on "charbon", meaning coal).

The only problem was that up till now the wine could only be drunk by members of the wine-growers' association. There was no appellation, so selling the Charbonnay was illegal.

In theory that should now change - as the Pas-de-Calais becomes one of France's new oenological terroirs.

- Published27 April 2015

- Published4 August 2015

- Published26 March 2013