French furore over spelling continues

- Published

The Academie Francaise want to make changes to the French language that have caused uproar

How Maurice Druon would have adored the tohubohu (or should that be tohu-bohu?).

Maurice Druon was the writer and wartime resistant who, as perpetual secretary of the Academie Francaise, lit the linguistic time bomb that is now combusting over Paris.

In 1990, responding to a request from then Prime Minister Michel Rocard, he compiled a detailed series of "rectifications" for the French language.

Around 2,400 words were affected. Druon's adjustments were intended to iron out anomalies, eliminate redundancies and "facilitate the teaching of spelling".

Little could he have imagined that, a quarter of a century later, his modest proposals would be creating such a furore.

The late Maurice Druon compiled the spelling reforms that are causing such controversy now

With the spelling changes to be included "as an option" in school textbooks for the first time this year, right-wingers are accusing the Socialist government of dumbing-down.

The education minister retorts with an angry diatribe against the Nicolas Sarkozy years.

Defining and defending

The new perpetual secretary of the Academie disowns the Druon changes.

Teachers and linguists thrash it out online.

There is even a rap song on the web: "In defence of the circumflex".

Maurice Druon would have loved it because he was a humorous man, who could spot media humbug a kilometre off.

But he would have been particularly amused by the notion, raised by some on the right today, that his linguistic retouches were in some way revolutionary, or pandering to the uneducated.

Druon was one of the most conservative characters to have walked the French stage in the last half-century. He adored the French language. Ensuring its strength and survival was his life's mission.

As he noted proudly in the preamble to his report, the job he was undertaking had roots that led back to the great Cardinal Richelieu himself.

When Richelieu founded the Academie in 1635, he gave it the task of defining and defending the language.

Periodically ever since, there have been changes to the rules of spelling. In 1835 for example, there was a major reform when endings in -ois were changed to -ais to reflect pronunciation.

Thus the old francois and anglois became the words we know today: francais and anglais. The writer Chateaubriand refused to adapt - but he stood in futile defiance against the tide of common usage.

So in drawing up his rectifications, Druon saw himself as just another of great sages who had opined over the centuries, adjusting the language to take account of changes wrought by time.

Nothing could have been further from his mind than some radical rehaul "to make it easier for the kids".

So why the huge fuss? I can think of three reasons.

The first is the media. When Druon made his proposals, there was no such thing as the internet. News of the changes filtered out in newspapers, and was given due deliberation - and that was that.

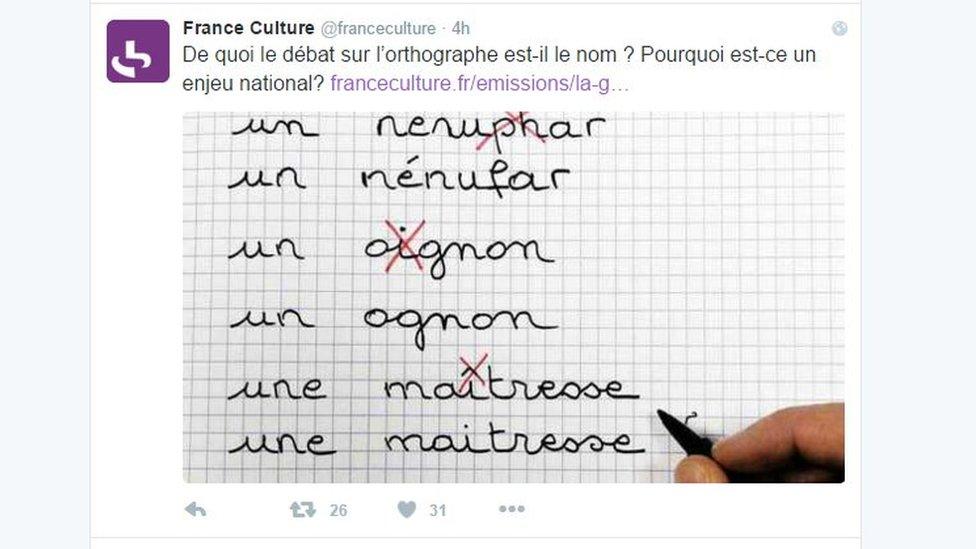

Today the slightest whiff of controversy sweeps across the media like a wind. Politicians feel obliged to take instant positions, and Twitter ups the ante with its flow of hyperbole.

What is lost is any sense of proportion.

Why is this a national issue? asks radio station France Culture

The second reason is the particular relationship the French do have with their language.

As Le Monde put it in an editorial this week, "language has been one of the founding elements of the French state, an essential component of the national identity".

Unlike English, which developed bottom-up, French was imposed from above by a powerful, centralising state. Regional languages and dialects were suppressed.

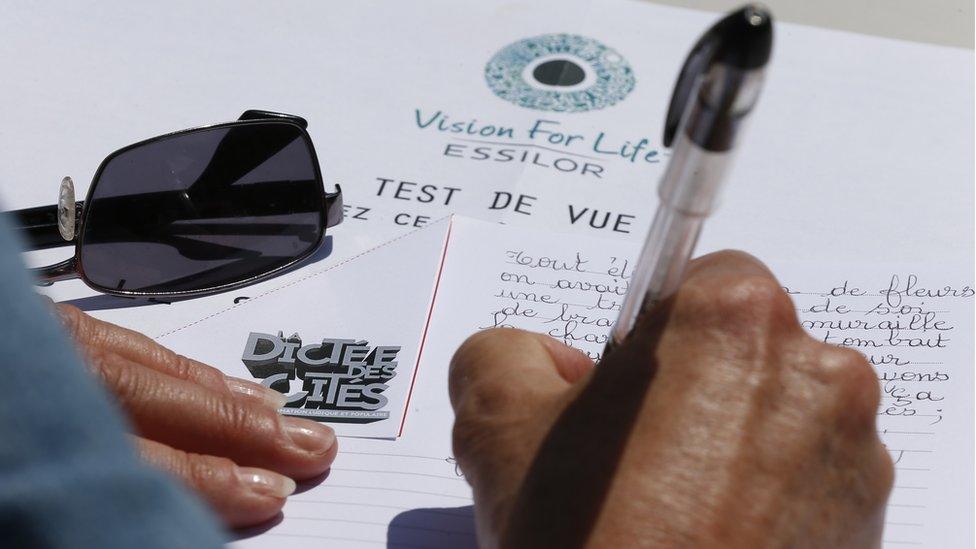

Mastering the language came to be seen as a hallmark of citizenship, whence the huge emphasis in schools on the dictee or dictation.

Today the grip of the dictee is beginning to loosen in schools, but there are still public dictee competitions. People feel attached to what they spent so much effort learning and they resent any bid to tamper with the rules.

Which brings us to the third reason why the Druon changes are causing such a stink - politics.

The row over the spelling reforms comes as the country is already tearing itself apart over identity and national culture.

So the debate over whether the circumflex should stay on the "i" or whether numerals take hyphens has become code for arguments about immigration and assimilation.

The right accuses the government of lowering standards in order to be as "inclusive" as it can. Left-wingers respond that if illogical spelling rules hinder social advancement, then they should be changed.

Even adults can take part in public dictation competitions

In reality the row is utterly pointless.

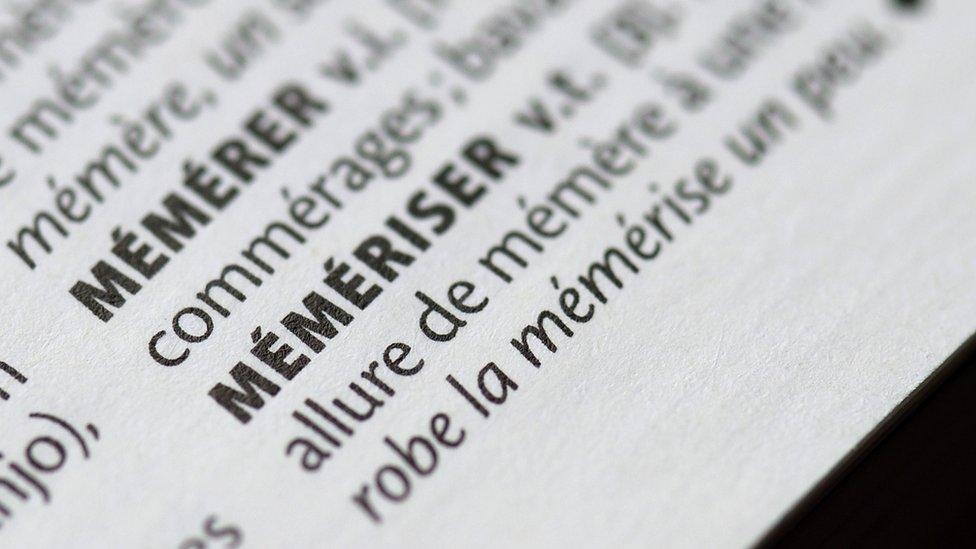

Some of the Druon changes have already gone mainstream (for example the shift in the umlaut from ambiguë to ambigüe, and the acute accent on média).

Others it is hard to see ever being accepted. Changing oignon to ognon may be logical (because phonetic) but it will not take hold.

As for the row over the circumflex on "i" and "u", contrary to what has been reported it is not set to disappear.

Druon lists plenty of exceptions (such as his beloved imperfect subjunctive as in suivît), and says where there is ambiguity the accent stays (so jeûne meaning fast, as opposed to jeune meaning young).

The largest category of changes concerns portmanteau words, often of foreign origin. Many of these can lose their hyphen, and pluralise more simply. Again time will tell.

For example - tohubohu. It comes from Hebrew, and means pandemonium.

- Published5 February 2016

- Published5 February 2016

- Published21 January 2016