Russian plaques mark Stalin's victims

- Published

Memorial plaques are being fitted to homes across Moscow

The rectangular plaques are small and simple. Etched into the metal there is a name, date of birth and occupation: radio technician, journalist, student.

Then come the dates of arrest and execution.

Fixed to buildings across Russia, the nameplates are gradually restoring the memory of some of the millions of victims of Joseph Stalin's political repressions.

The initiative of a group of activists, it is also a direct challenge to the growing number of Russians who see the Soviet leader in a positive light.

A group in Moscow wants its latest project to remind people of the dark side of Stalin's rule.

As the latest plaques were screwed to a house in central Moscow recently, a small crowd gathered.

Olga had brought a black-and-white photograph of her grandfather, Mikhail Solonino. The university linguistics professor was arrested one October morning in 1935, denounced as an "enemy of the people".

He was executed in the Karlag labour camp two years later.

"Today he's getting something due to him," Olga commented, watching as the modest plaque was fixed to his former home.

"This is not just a civil ceremony. There is something sacred about it. It is so very important that people can read the names of people who disappeared completely in time."

The Last Address project has received more than 1,000 applications requesting plaques to those who perished in Stalin's paranoia-fuelled purge of supposed traitors.

The group of activists involved seek the agreement of residents before arriving with their electric drills but it is not always easy.

'Not VIP victims'

"People tell us they don't want their buildings turned into cemeteries, that the plaques are depressing," project-initiator Sergei Parkhomenko explains.

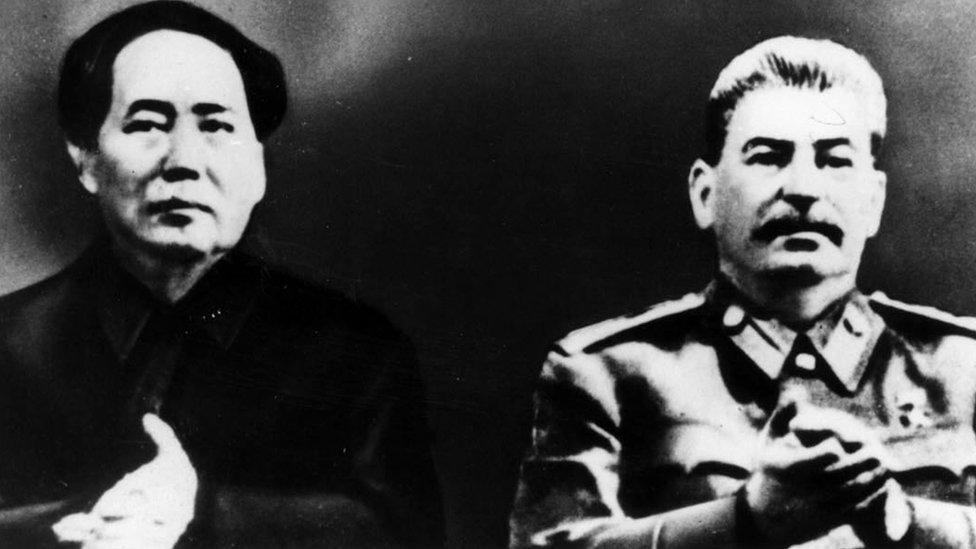

Stalin dominated the USSR for three decades

"Or they don't want their children to see them, because it's too gloomy."But those we're remembering are not just VIP victims. They're ordinary people."

The Great Terror reached its frenzied height in 1937 and 1938.

As well as Communist Party officials, factory workers, artists and even housewives were among the vast numbers imprisoned or killed as "counter-revolutionaries".

The government is drawing up a new state policy to commemorate the victims of political repression.

Initial documents make clear that "continuing attempts to excuse" or deny that history are "not acceptable" and a national memorial is finally planned.

'Foreign agent'

And yet recent polls show that Russians increasingly see Stalin as an "effective manager" or war hero, rather than a tyrant.

Opposition activists are regularly labelled "enemies of the people" on state TV programmes and Memorial, the organisation long devoted to restoring the memory of the repressions, has been branded a "foreign agent".

It is accused of blackening Russia's image for Western paymasters.

"No-one has ever forced us to face up to what happened," Roman Romanov explains.

He is director of a new Gulag Museum in Moscow and recalls that there was even opposition to that when it opened.

"Of course we should remember the victories, the heroic episodes from our past," he says.

"But we have to recall the tragic pages of history too. It's like a bitter pill that people can say they don't want - but they need it."

Photographs of Stalin's murder victims have been left by relatives on tree-trunks and alongside plastic flowers stand part-buried by snow

Photos of execution victims have appeared on trees

Just a few steps into the forest off one of the main roads out of Moscow, there is an even starker reminder of why.

Kommunarka was once the summer house of Gennrich Yagoda, Stalin's secret police chief.

After his execution, at least 10,000 purge victims were brought here by the truckload and buried.

The Orthodox Church is now in charge of the land and a wooden cross and memorial stone funded by donations offer "eternal remembrance" to those killed.

Their photographs, left by relatives, flap from the tree trunks and plastic flowers stand part buried by snow.

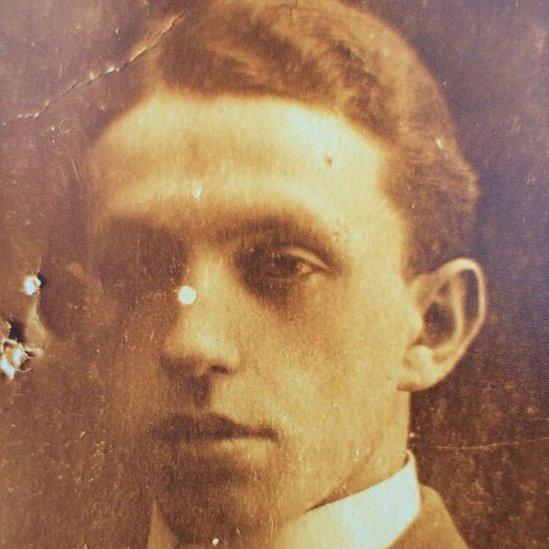

Gennrich Rubenstein was arrested as a "counter-revolutionary" in 1937 and then executed

"Our mother was 11 when she lost her father," Anna Bogorad recalls, on her first visit to her grandfather's burial site.

"He was shot, wrongly, like so many others."

Gennrich Rubenstein was a manager on Soviet Railways, arrested as a "counter-revolutionary" in 1937 and then executed. The grainy, sepia photograph Anna holds shows a smart young man, hair carefully parted to one side.

She has just had a memorial nameplate fixed to his home.

"There are still people who don't want to know about this," Anna reflects, bitterly.

"Especially young people who are taught history in such a way now that these victims are justified.

"They say, 'Well, we leapt forward. We created a country of tanks from a country of ploughs. So there were victims? So what?'"

Eight decades on, the Gulag museum now has plans to mark out the graves at Kommunarka and erect a memorial with the name of every victim buried there.

But back in the city centre, the Last Address project has already installed more than 170 of their metal plaques on prominent buildings where they can no longer be ignored.

"Our aim isn't just to put nameplates on every building in the country, although you probably could," Sergei Parkhomenko says. "What's important is to gather people around them. So that they explain what happened to those who don't know, and tell their children."

Correction 4 March 2016: This report has been updated to clarify the number of Stalin's victims.

- Published22 February 2016

- Published28 January 2016

- Published30 December 2015

- Published8 December 2015

- Published6 August 2015

- Published29 January 2016

- Published9 September 2015

- Published14 May 2015