Migrants find new routes as old ones close

- Published

The Balkan route may officially be closed, but the Asylum Information Centre in Belgrade is very much open - and doing a roaring trade.

The location is central but insalubrious - squashed between fast-food shops at the scruffy end of Nemanjina Street, within sight of the city's main railway station.

The hubbub around the door and signs in the window handwritten in Arabic script indicate that arrivals from the Middle East are still coming to Serbia's capital.

Inside, there is organised chaos. On the ground floor, young men lounge awkwardly in hard-backed chairs, waiting for their turn on the computers lined up on one side of the room. Those in front of the machines don headsets and hold ebullient Skype conversations.

The centre is busy every day

Upstairs, the atmosphere is completely different. Bewildered-looking families gather in a stuffy "safe space" operated by Save The Children. Parents usher their children over to a pile of toys, while a small boy cries inconsolably. The distinctive aroma of the refugee trail - damp, unwashed clothes - begins to fill the room.

"They are Yazidi people from Iraq," says Marjan, a translator struggling to find a common language with the new arrivals.

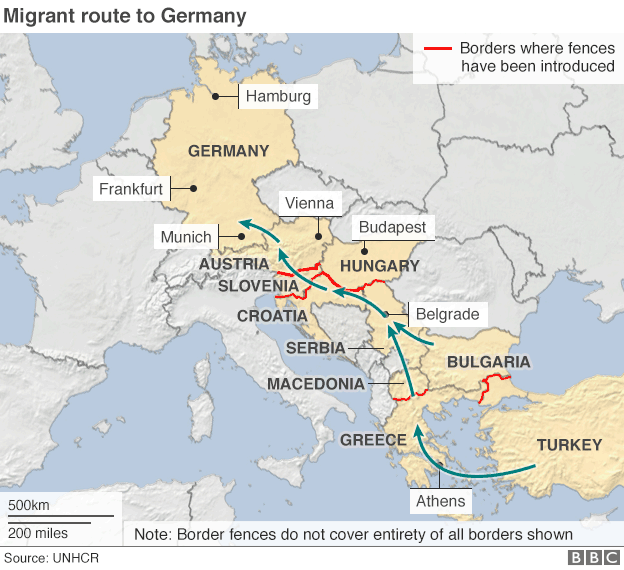

There are more than two dozen people in this extended family group. They did not follow the classic route to Serbia via Greece and Macedonia, but came over the country's eastern border with Bulgaria.

In the centre's strip-lighted, windowless meeting room, the overflowing ashtrays and half-drunk mugs of Turkish coffee suggest that it has been a stressful morning. The centre's manager, Vladimir Sjekloca, breaks off to explain the situation.

"There are always people in Belgrade," he says. "Around 400-500 a day."

Alternative route

Vladimir says the increasing restrictions imposed by countries along the Balkan route - and finally its official closure (although hundreds of people have found a way through the border fence to cross from Greece into Macedonia) - have not stopped people seeking a way to western Europe. They have just changed the means.

"Coming in through Bulgaria - it's an old smuggling route and it'll be used more often. The Afghans tell us, 'It's cheaper to come that way [than the sea crossing from Turkey to Greece] and anyway we can't swim.'"

Vladimir Sjekloca says people are finding different ways into Serbia - but still face dangers

Before its closure, countries along the route had been co-ordinating transport so that people would be taken from Macedonia to Slovenia's border with Austria on officially provided trains and buses. It was a reasonably smooth process which greatly reduced the possibility of refugees falling into the hands of people smugglers.

But now people who are desperate or determined to reach western Europe are once again dealing with unscrupulous elements.

"The journey through Bulgaria is full of ill-treatment," says Vladimir.

Said from Afghanistan was turned back at the Croatia border and now hopes to settle in Serbia

"People suffer at the hands of the mafia and people smugglers - and they don't get protection from the system. In fact, they can get ill-treated by the Bulgarian police or put in jail. They have set dogs on refugees - we've seen people with dog bites who've been severely beaten by the mafia or the police."

Smugglers 'our only hope'

Some of the people at the Asylum Information Centre have learned the hard way that people smugglers and even the authorities may not have their best interests at heart.

Ali Hashem Zade, a 27-year-old native of Tehran had hoped to find work in Europe to help support his two infant daughters.

Iranian Ali previously paid a people smuggler but now says: "It's better to rely on God than smugglers"

But when Macedonia blocked entry to Iranians, he placed his trust in a trafficker from Pakistan.

"The smugglers were our only hope after they closed the border to Iranians. He took €250 (£195) from me - but he had a different price for everyone. He charged some people €1,400 - but he actually ran away, and I ended up wandering along the border for two days - I had to burn some of my clothes to start a fire," he says.

Ali says he found his way over the border by using his phone's GPS - but the same method did not work when he tried to cross from Serbia into Croatia. He claims the Croatian border police beat him and his friends when they caught them.

Still, he means to try again.

"I have no money - so I will rely on God's will. It's better to rely on God than smugglers."

Country of transit

Other people at the Asylum Information Centre are deciding to stay in Serbia - for now, at least. Taxis arrive to take the families to another asylum centre in Krnjaca, in the suburbs of Belgrade.

These buildings used to accommodate factory workers; now they house asylum seekers

In the Yugoslav era, this rundown facility with the feel of a military barracks used to be workers' accommodation for an adjacent factory. Now the single-storey blocks house asylum seekers waiting for their claims to be processed. They share the facility with a handful of refugees displaced in the Balkans conflicts of the 1990s.

Ivan Miskovic from the government's Refugees Commissariat explains that people stranded when the Balkan route shut have a number of options. As well as asylum in Serbia they include repatriation, resettlement in a third country or an application to be reunited with family members who have already made it to western Europe.

"I think we did our job by offering them all the possibilities," he says. "But our previous experience tells us that Serbia is not their destination, but their country of transit."

Serbia has consistently taken a pragmatic approach to the refugee crisis - whether that has meant helping people on their way when the borders were open, or, more recently, mirroring the entry restrictions of neighbouring countries. Now there is a sense of realism about what the coming weeks might bring.

"The borders are not hermetically closed," says Ivan Miskovic. "It is inevitable that more people will come in. Even if they come in an irregular fashion, they must be registered - and we can help them to be less vulnerable.

"But even if they start the asylum procedure [to stay in Serbia], they are simply buying time to leave the country when they find a suitable connection."

In other words, the Balkan route carries on.