1916 Easter Rising: Reflections on a rebellion that changed Ireland

- Published

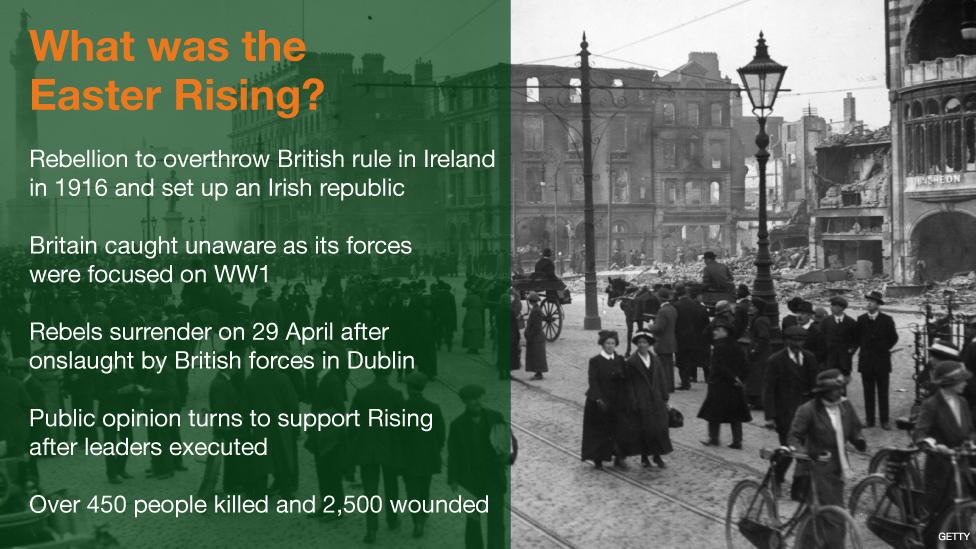

More than 450 people were killed during the rising in Dublin in April 1916

As Ireland remembers the 1916 Easter Rising this week, many people are wondering whether the violent rebellion that claimed almost 500 lives was necessary to gain independence for 26 of the country's 32 counties from the United Kingdom.

BBC News NI's Dublin correspondent Shane Harrison gives his thoughts.

I remember meeting a senior backroom figure in Sinn Féin in Dublin in 2014 a couple of months before the referendum on Scottish independence.

"Imagine, we have had to fight tooth and nail for everything, resort to violence, everything, and suffer our own deaths and imprisonment, and they are getting a referendum on whether they want to be free and independent", he said.

John Bruton, a former Irish prime minister, was also thinking about the Scottish experience at about the same time.

In a series of articles and interviews at the time, he, a long-time critic of violent republicanism, argued that the 1916 Easter Rising was a mistake.

He said Scotland was about to vote "without loss of life, without the bitterness of war".

"Ireland was given a similar opportunity 100 years ago," he said, "to move through home rule, towards ever-greater independence, gradually and peacefully, when home rule for Ireland became law on 18 September 1914.

"Ireland could have followed the same peaceful path towards independence that Scotland is now considering taking."

Problematic

Those who criticise the rising often argue the rebels had no democratic mandate and set a dreadful precedent that could be used to justify the loss of life related to the 30-odd years of Northern Ireland's Troubles.

The critics are right - the rebels had no democratic mandate.

But neither had the British a democratic mandate to govern Ireland - they did so by force of arms.

And the use of words like "democracy" to describe events of the time is problematic.

There was no "democracy" at the time as we now understand the term.

An onslaught by British soldiers led the rebels to surrender

There was no universal suffrage - it's estimated that only about 30% of the population could cast their ballots because of property qualifications and women not having the vote.

The critics are also right that the events of 1916 have been used to justify violent republicanism ever since.

But within two years of the rising, the population of Ireland gave a significant endorsement to the rebels' aims in the 1918 general election when women voted for the first time.

There was, however, significant opposition in the north-east, in what would later become Northern Ireland, with its Protestant and unionist majority.

Mutiny

When it comes to violence we must always remember that the "blood sacrifice" associated with the rising paled in comparison with the mass slaughter taking place on the western front during World War One.

And unfortunately, violence, or the threat of it, worked.

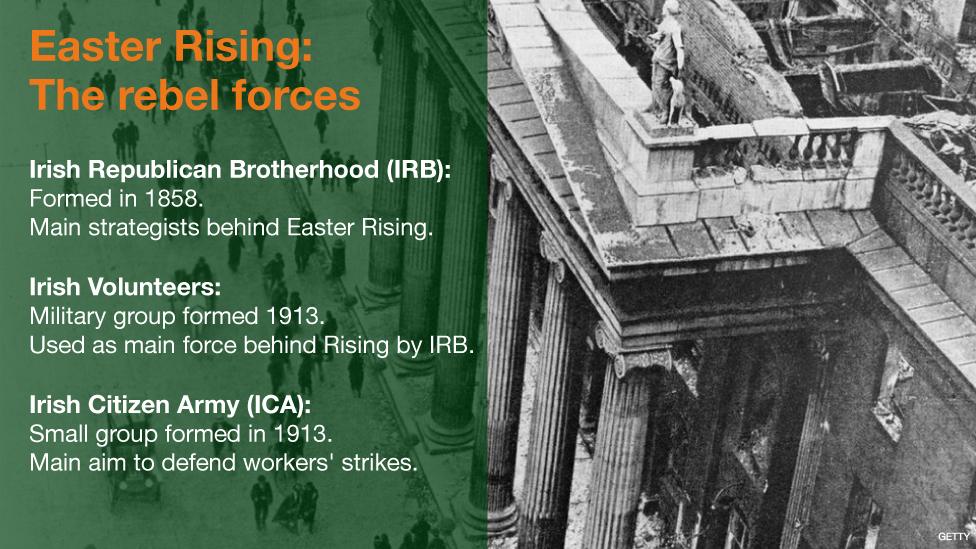

It certainly worked for the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) in its opposition to Home Rule.

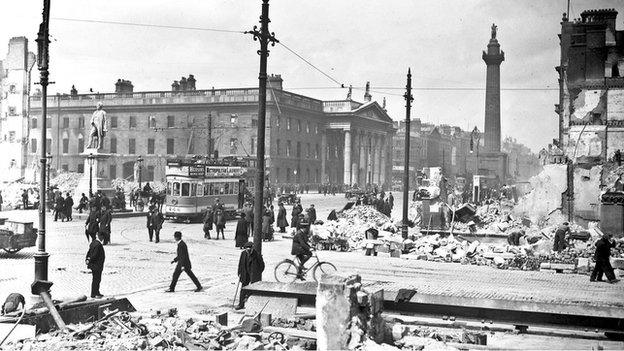

Dublin crumbled as the rising failed, but the event was a seminal moment in Irish history

The UVF, a Protestant and unionist paramilitary group, landed German weapons in 1914 and was supported in its aims by the mutiny by British Army officers in the Curragh against the possibility of marching against the loyalist organisation.

The outbreak of World War One delayed a limited form of home rule but events, not least of which was the rising, made it all irrelevant.

The British establishment at the time had a contemptuous view of the mainly Catholic southern Irish, as is evidenced in Fatal Paths, the highly-regarded book by the eminent historian Ronan Fanning.

Unlike the case of Scotland it is inconceivable there would be an Irish prime minister, and certainly not a Catholic one.

Overreaction

One thing I have always found curious is this: why did public opinion in Dublin and southern Ireland change so quickly from hostility to the rebels to support for their aims in the 1918 election?

Some say it is because the British executed the leaders of the rising, but they were, in British terms, "traitors".

Others add that British overreaction and mass arrests contributed, as did the threat of conscription at a time when Irish men were already dying in their thousands at the frontline.

I wonder whether there was more latent support for the rebels than people at the time were prepared to admit, because of fatigue with the long-delayed desire for home rule and possibly because of what was happening at the war front.

Nobody can say with certainty that 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland would eventually have got independence arising from home rule.

But what we can say is that the 1916 Easter Rising certainly accelerated it.

Given unionist opposition, it seems almost inconceivable that what is now Northern Ireland would have formed part of that independent entity.

Freedom

As a result of 1998's Good Friday peace agreement there is constitutional acceptance in the Republic of Ireland that Irish unity will not happen until a majority in Northern Ireland vote for it.

But it is also the case that the use and threat of force by both loyalists and Irish nationalists and republicans poisoned relations on the island for the best part of a century.

As the Sinn Féin figure must know, comparisons between the Ireland of 100 years ago and Scotland today are not apt.

Easter 1916, with what the poet WB Yeats called its "terrible beauty", changed southern Ireland fundamentally.

- Published23 March 2016

- Published22 March 2016