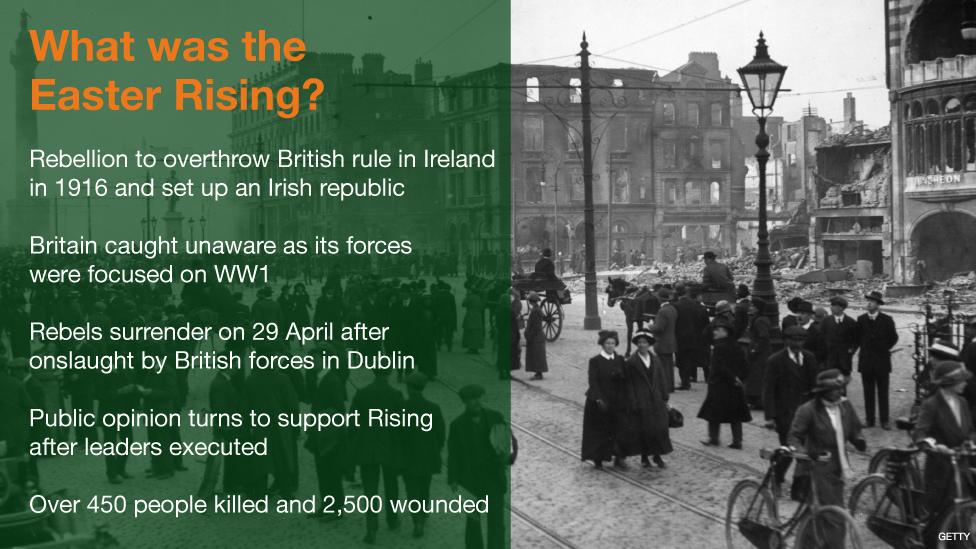

Easter Rising 1916: 100 years of Anglo-Irish relations

- Published

In 2011, Queen Elizabeth II and the then Irish President Mary McAleese stood side by side in Dublin paying tribute to those who took up arms and fought against British rule in Ireland

Ahead of the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising by Irish rebels against British rule on the island, BBC News NI's Dublin correspondent Shane Harrison looks at how relations between the two states have changed over the last 100 years.

It was a long time coming - the first state visit by a reigning British monarch to independent Republic of Ireland.

On a cloudy 17 May 2011, Queen Elizabeth II and the then Irish President Mary McAleese both bowed and honoured those who took up arms and fought against British rule.

It was all such long way from Easter 1916, when Irish rebels took over Dublin's General Post Office (GPO) and proclaimed a republic.

The executions of the rebellion's leaders, the arrests of so many by the British afterwards and the threat of conscription to fight for Britain in the bloody First World War all helped quickly to change public opinion about the Easter Rising that had been initially hostile.

"The conscription crisis had in some ways, I think, as enduring an impact on Anglo-Irish relations as did the 1916 Rising," says Prof Eunan O'Halpin from Trinity College, Dublin.

In the general election of 1918, most of southern part of Ireland voted for Sinn Féin and its goal of an independent republic, while unionists dominated in the northern part of the island.

The War of Independence broke out after the newly elected Irish MPs refused to go Westminster and set up a Dáil Éireann, an independent Irish parliament.

An Irish tricolour flies above Dublin's General Post Office (GPO) - the headquarters of the Irish rebellion against British rule in Ireland in 1916

In the resulting 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, the six Northern Ireland counties stayed British but the remaining 26 counties were given self-government under the British crown; it was initially known as the Free State.

The treaty led to a brief civil war: Michael Collins on one side, Eamon De Valera on the other. Collins led the Irish delegation at the Anglo-Irish Treaty talks and supported the deal, De Valera opposed it.

De Valera's anti-agreement forces were defeated but he later reconciled himself to the new dispensation and led his party into government.

In the late 1930s, while De Valera was in power, he ended the role of the crown, took control all the ports from the British and declared Irish neutrality during World War Two,

A British Pathé news reel of the time captures London's hostility to the Irish prime minister's decision not to get involved saying: "Mr De Valera's neutrality permits German agents to establish themselves in an easy position for the collection of vital information."

From the end of WW2 until the civil rights campaign in Northern Ireland and the later outbreak of the Troubles, British-Irish relations remained largely on an even keel, despite the 1948 decision to declare a republic.

A delegation of Irish leaders including Michael Collins (centre) signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London in 1921, which led to the partition of Ireland

During the unrest, the Irish government strongly objected to how the minority Catholic and nationalist community in Northern Ireland was treated and discriminated against; but unionists and the British saw this as interference in the United Kingdom's internal affairs.

And yet in spite of those often heated rows, both London and Dublin joined what would become the European Union (EU), resulting in much more contact between leaders, ministers and civil servants.

"We saw one another in a different light, it was no longer big Big Brother and Smaller Brother," says John Bruton, a former Taoiseach (prime minister).

"We were all together in a union that contained many other big countries and smaller states and were were able to cooperate in a much more normal way. And that, I think, has completely changed the type of relationship that we've had."

Former Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) John Bruton said the EU helped to normalise Anglo-Irish relations

Prof O'Halpin agrees, saying that such was the Irish economic dependence on the UK that Dublin, to become more independent, had to follow London into was then called the Common Market.

"For Ireland to prosper, for Ireland to lessen its dependence on the British economy, ironically she had to follow Britain into this new European entity," he adds.

Many believe that changed relationship, which Mr Bruton described, was evidenced in the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, external that gave the Republic of Ireland a say in Northern Ireland's internal affairs and then later with the power-sharing Good Friday Agreement of 1998., external

In 1985, the then Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement

Once again, both governments were at one but this time with the support of most of the political parties in Northern Ireland including the Ulster Unionist Party, but not the Democratic Unionist Party at that stage.

So, now 100 years after the Easter Rising there is another potential landmark in relations between the two states, the British referendum on its membership of the EU.

A British exit (Brexit) from the EU could have major implications for the two islands with the Irish deeply worried that UK voters may choose to leave with serious consequences for working relations between the two countries and for the peace process.

The wheels of history keep turning.