Migrant crisis: European Commission proposes asylum reforms

- Published

Under the current system, EU countries have the power to return asylum seekers to the first EU state they entered

The European Commission has come up with alternatives for a "more humane and efficient" way of handling asylum in response to the migrant crisis.

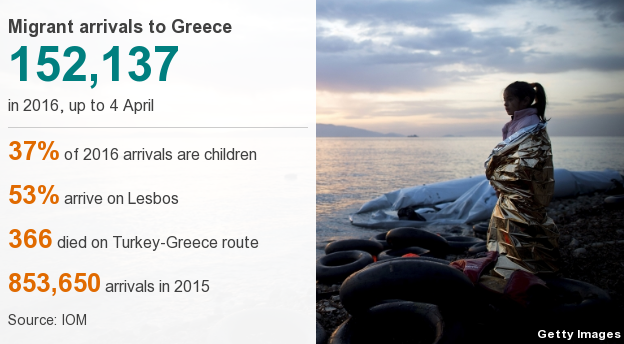

The current EU system is widely thought to have failed because of the influx of a million people through Greece.

Among the options is a plan to scrap a rule for refugees to claim asylum in the country they arrive in.

The so-called Dublin regulation proved unworkable when Germany opened the door to Syrian refugees last August.

European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans argued the current system had to change, saying: "We need a sustainable system for the future, based on common rules, a fairer sharing of responsibility, and safe legal channels for those who need protection to get it in the EU."

As most irregular migrants in the past three years have arrived in the EU in Greece and Italy, the two countries have been left with the majority of cases.

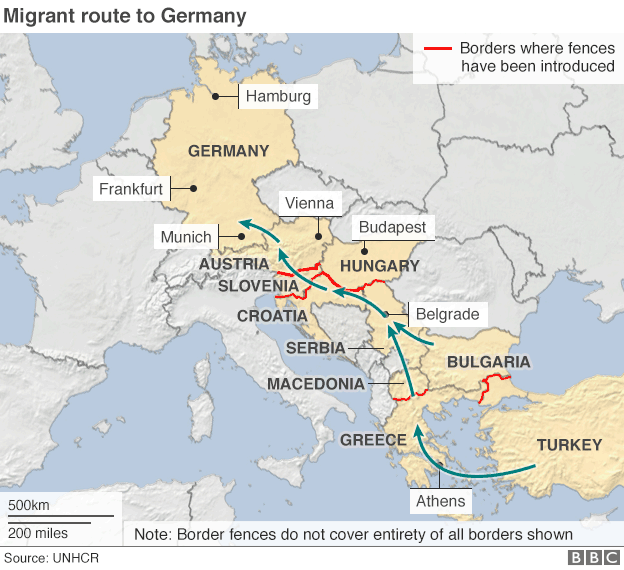

Both states stopped registering every arrival and most new arrivals on the Greek islands since August continued their route through the Balkans.

Eventually several countries put up fences and border controls in an attempt to halt the influx.

Mr Timmermans said there were two options

Amend the first-country rule with a "corrective fairness mechanism" to provide help to a struggling country

Scrap the the first-country rule altogether and move to a system based on redistributing refugees more evenly.

To put a stop to "asylum shopping", rights for asylum seekers would be made conditional on being fingerprinted and remaining in the relevant EU country.

The Commission is keen to beef up the powers of the EU's asylum agency, EASO, and suggests it could carry out any redistribution of asylum seekers.

In light of the Islamist attacks on Paris and Brussels, it has also called for better sharing of intelligence among EU member states.

Several countries do not want to see wholesale changes to the asylum system.

While Italy wants to see it abolished, Germany and the UK are keen to keep the existing first-country system, which enabled the British government to deport almost 2,000 asylum seekers in 2015.

The Berlin government would like a relocation scheme established for asylum seekers to alleviate the pressure on Greece and Italy, and halt the influx of migrants.

More than one million migrants have arrived on the Greek islands since the start of 2015

An EU deal to return migrants to Turkey from Greece came into operation this week

Whichever proposal is finally agreed, the UK cannot be forced to take asylum seekers as it has opt-outs from EU asylum policies, BBC Europe correspondent Damian Grammaticas explains.

Under an EU deal aimed at cutting off the migrant route through the Balkans, Greece has begun deporting migrants to Turkey if they do not apply for asylum or if their claim is rejected.

However, the Athens government paused the operation on Tuesday, a day after the first boats took 202 people to the Turkish port of Dikili.

Hundreds more are due to be removed later this week. The Greek migration ministry said the number of migrants arriving from Turkey had slowed to 68 in the 24 hours to Wednesday morning, down from 225 the day before.

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said it was evidence that the deal with the EU was working.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.