Nightly people's protests animate Paris

- Published

- comments

Crowds have been attracted nightly to Place de la Republique

Since the end of March, hundreds of people have been gathering every evening in the Place de la Republique in Paris.

Dubbed Nuit Debout, external (Up All Night), it is a self-styled "popular assembly" in which participants share views about politics and the state of the world.

As night descends, the speakers stand patiently in line and, turn by turn, take the microphone for their allotted five minutes.

Before them, sitting in twos and threes on paving stones, the young audience responds with the occasional cheer or boo.

Not that there is a huge amount to react to. The speeches are rambling and platitudinous.

One orator says the essence behind society should be "values" - but she does not say which.

Another urges an end to hierarchy - "no more pride, no more ego - just ideas".

A third wants to speak of human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

One theme that recurs is the need to tolerate divergences of opinion. This is significant. Two nights previously, one of France's best-known philosophers - a man who a generation ago would have himself been at the mike - was spat on and told to leave.

The protests are quite a spectacle

Both speakers and listeners appear to be mainly students - an impression confirmed by a tour of the various "stands".

The feminists are in a large huddle, and I am asked not to take photographs. Elsewhere, a screen shows a laborious film made by a woman who took a job distributing junk mail and wants to expose the exploitation.

There is a group of anti-speciesists, external, and a "TV studio" (TV Debout!) consisting of a camera and white sheet and a lap-top. No-one is using it.

Someone has planted a minuscule vegetable patch beneath a tree (Jardin Debout!).

One banner calls for a new French constitution. Another proclaims the "convergence des luttes" - the ultimate left-wing dream: the coming together of all the struggles.

It is like wandering through a university campus during a sit-in. The same mixture of wide-eyed joy and po-faced earnestness. The same thrashing out of texts that no-one will read. The same evanescent self-importance.

Nuit Debout (Up All Night)

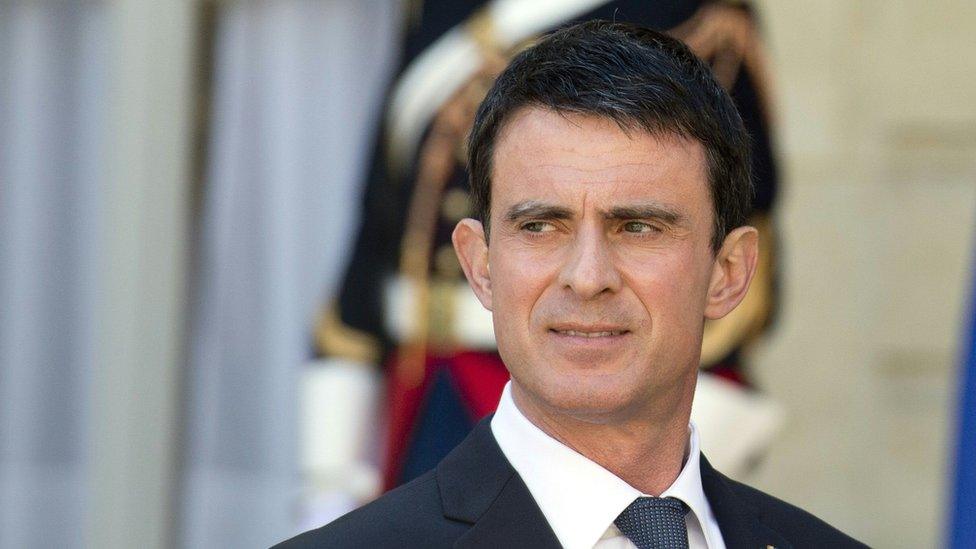

Social movement that began on 31 March, arising out of protests against Prime Minister Manuel Valls's labour market reforms

Has held nightly rallies at Paris's Place de la Republique since then

Has since spread to other French cities, as well as cities in Belgium, Germany and Spain

The activists, organised through social media, are mainly left-wing

Has been compared to the Spanish Indignados citizens' movement and the Occupy anti-globalisation movement.

Public status

All of which would be perfectly unexceptionable, were it not for the fact that - this being France - the Nuit Debout movement has been accorded a public status that it does not remotely deserve.

The media - with rare exceptions - have been predictably breathless in their reporting of this "democratic awakening".

Passions can run high

The impression is put about that la jeunesse (the youth) is once again - as in May 1968 - doing a service to society by reclaiming debate from a decrepit political establishment.

Worse, the politicians themselves go along with this myth. No-one dares say boo to a "popular manifestation" that borrows its imagery from the country's revolutionary past. Even some right-wing politicians have said they are "solidaire".

The crowning irony is that - in the face of la jeunesse en colere (angry youth) - the Socialist government has already made major concessions.

The origin of Nuit Debout was the protest movement against Prime Minister Manuel Valls's vaguely pro-business new labour law.

But under pressure from President Hollande (who is petrified by the prospect of youth on the streets), Valls has not just removed the more contentious clauses - he has also offered 500 million euros a year in new grants for the young.

Manuel Valls's Labour law reforms have provoked a strong reaction

There is even talk now of extending welfare payments that normally kick in at 25 to 18-year-olds - even though the cost of that would be a ruinous six billion euros a year. This in a country committed - supposedly - to bringing down its deficit of 70 billion euros.

In reality, Hollande has made a very political calculation. Though protests against the labour law will no doubt continue, their bite has been removed.

The threat is over, and he can keep alive - for now - the fiction that he will be the left's natural candidate in next year's presidential race.

Meanwhile, the Nuit Debout movement will remain as a dwindling, harmless legacy of the president's last bid to reform. Harmless, because the Place de la Republique protesters are now static, tame and increasingly absorbed in their utopian irrelevance.

But the deeper lesson of the episode is more troubling.

France is a country prone to self-deception. Its obsession with the symbols of a revolutionary past blinds it to the realities of an undesired present.

Movements like Nuit Debout sustain the delusion that left-wing ideas are thriving. They are not.

The country is increasingly moving to the populist right - not least out of exasperation at a discredited orthodoxy.

- Published11 April 2016