Migration crisis: Italy threatened by national crisis

- Published

Syrian restaurants have opened in Rome but Italians are worried by new arrivals

Whizzing mopeds, chiming church bells, vibrant piazzas and bustling cafes. Quintessential images of Italy as many of us believe it to be.

But walk through Rome's Piazza Vittorio these days and you could be forgiven for believing you were in London.

You hear Arabic here and Punjabi there. Romanian, Chinese and Afghan voices fill the air.

Cheap Korean, Indian and Egyptian eateries try to entice you with flashing neon signs.

Multicultural Italy is a relatively new phenomenon but it's a growing one.

Syrian restaurant owner Mohidyn Oudstwani tells me that conquering Italian hearts and palates is easier than you might think.

Syrians and Italians have much in common, he says. Both spend much of their time eating or talking about good food, and the lives of both peoples revolve around their "mamas".

But co-existence - coesistenza as it is known here - is delicate and hard-won.

When Imam Sami Salem, originally from Egypt and now a well-known figure across Italy - founded a mosque in a graffiti-covered, working-class district of Rome 20 years ago, Italian neighbours pelted the congregation with tomatoes, cigarette butts and dirty water.

But Imam Salem decided to fight prejudice with openness. He threw open the doors to his mosque and became involved in local charities and community work.

One of the reasons Italy has fewer Islamist radicals than many other European countries, he believes, is because it doesn't have ghettos or isolated Muslim neighbourhoods like France's banlieues.

Imam Salem, originally from Egypt, has become a well-known figure in Italy

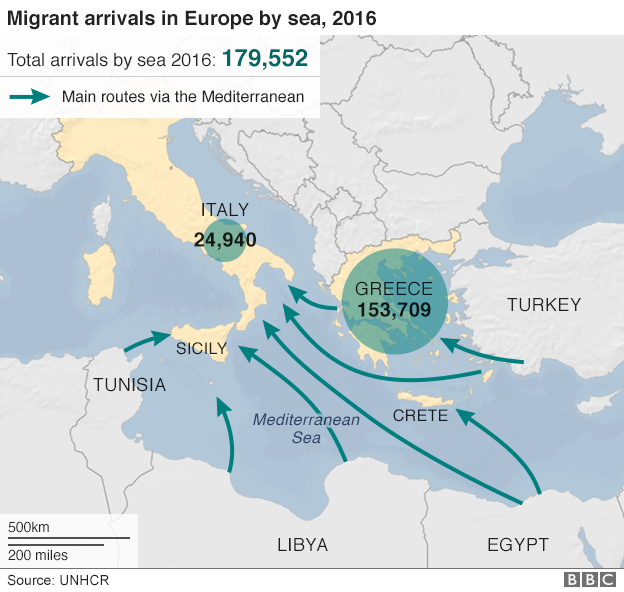

The number of migrant arrivals in Italy has been steadily increasing in recent weeks

Familiarity breeds tolerance, says Imam Salem.

But Italian tolerance is now thinning, following the jihadist attacks in Brussels and Paris, combined with Italian fears over the influx of migrants arriving in Italy via north Africa.

Three hundred thousand new arrivals are expected here this year, most crossing in dinghies from Libya.

Finance Minister Pier Carlo Padoan (R) says Italy is worried for several reasons

But smugglers are increasingly heading to Italy from Egypt too and, with the Balkan route from Greece now firmly shut to migrants, there's talk of the desperate trying to access Italy after crossing mountain paths in Albania.

Italians feel under siege. There is talk here of a looming national crisis.

"Of course we are worried," says Italy's Finance Minister Pier Carlo Padoan.

"We are worried first of all from a humanitarian point of view, from a security point of view, and then of course from a financial point of view. The cost of migration has been substantial."

Mr Padoan complains that the EU left Italy alone with its migration crisis for too long.

He points out that Italy was faced with mass arrivals long before Greece and that the EU refused to acknowledge until recently that Italy's coastal borders were in fact Europe's common southern flank.

Now he is calling for a common EU migration strategy and a common EU migration fund to help front-line countries like Italy.

In the meantime he wants more flexibility in eurozone financial rules, to compensate for the losses Italy has suffered due to mass migration.

The country's finance minister has been struggling to speed up growth after a record long recession. Italy's public debt measured against GDP is the biggest in the eurozone after Greece.

Italians feel that the EU owes them.

A strong air of resentment began to waft down the corridors of power in Rome as soon as the EU signed an agreement with Turkey to deter migrants from trying to reach Greece.

The man dubbed Prime Minister Matteo Renzi's "Mr Brussels" believes the EU has to commit itself to a new relationship with Africa, to help deter migrants trying to reach Italy.

Sandro Gozi, Italy's Secretary for European Affairs, told me that in the long term there had to be less incentive for people to risk everything to come here to Europe. But in the shorter term, a cash deal had to be drawn up with North African countries similar to the EU-Turkey agreement.

Turkey has now been offered up to €6bn (£4.75bn; $6.8bn) by the EU to stop migrants coming to Greece.

Italians believe as many as 300,000 migrants will arrive on their shores this year

Anti-immigration politicians now warn that Italy is simply full

Italy says the total of €1.8bn so far put forward by the EU for the whole of Africa is laughable.

What Italy is keen for is the EU to push for bilateral deals with African countries, to make it easier to send economic migrants and failed asylum seekers back home.

For the moment, most migrants choosing the people-smugglers' route to Europe via Italy come from sub-Saharan Africa.

But Syrians and others refugees are now expected here too, with other routes to Europe closed.

Gianluca Pini, an MP whose increasingly popular opposition Northern League party is widely associated with anti-immigration sentiment, told me simply that Italy was full.

Italy has no more money, no more space, no more facilities to help these people, he insists.

Like Greece, Italy is a gatekeeper to Europe along its southern shoreline.

Like Greece, Italy in the past waved migrants onwards and northwards towards richer neighbours.

But with northern borders now firmly shut, migrants still streaming in and difficulties deporting even failed asylum seekers back home, Italy says it is not waving, but drowning.