Is Europe lurching to the far right?

- Published

- comments

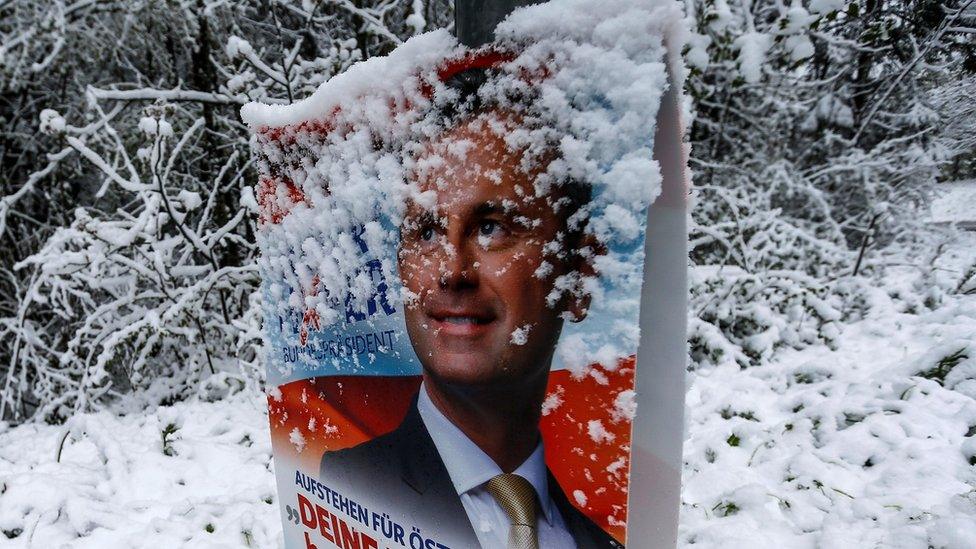

Extreme conditions - what explains the rise of right-wing populism in Europe, such as the success of Norbert Hofer in Austria?

A ripple of concern shivered across Europe this week in establishment circles after a right-wing populist candidate stormed to pole position in the first round of Austria's presidential election.

"Triumph for the extreme right," proclaimed Spain's El Pais newspaper. Britain's Guardian warned of "turmoil" ahead. Italy's Corriere della Sera bemoaned a victory for the "anti-immigrant far right" while Germany's Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung called on traditional political parties to "listen to this wake-up call!"

Most publications identified some link between Norbert Hofer's strong showing and Austria's centre-stage role in the EU's migrant crisis.

Europe's nationalist surge, country by country

Migrant crisis in seven charts

"In Austria, European governments see a mirror of their own future. Social tensions are rising," noted another editorial predicting the rise of Europe's far right.

But this writer wasn't talking about Sunday's vote.

Trotskyist journalist Peter Schwarz penned his thoughts 16 years ago, back in February 2000, when the Freedom Party (FPOe) first joined an Austrian government.

At the time, the party's charismatic and controversial leader, Joerg Haider, had provoked condemnation at home and abroad with his praise for Hitler's Waffen SS, with his strong anti-immigrant stance and Eurosceptic views.

The rise of Joerg Haider's Freedom Party in Austria 16 years ago prompted outrage - now there is little more than a raised eyebrow

I was living in Vienna then and reported from amongst the tens of thousands of anti-Haider protesters chanting "Never again!" in Heldenplatz - the emblematic square in central Vienna where Hitler chose to celebrate the annexation of Austria in 1938.

Europe was appalled at the inclusion of the Freedom Party in government. For the first time in EU history, all other members imposed sanctions on one of their own.

Diplomatic relations with Vienna were frozen. Austria was ostracised.

Then. But not now.

Now European eyebrows are raised, but little more than that.

Austria is hardly a novelty these days. Resurgent right-wing populist groupings shout anti-immigration and Eurosceptic slogans across much of the EU.

They find acclaim amongst large chunks of the electorate in Italy, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Greece, France and the Netherlands, for example.

So does this mean that Europe is veering to the far right? I would argue not.

A number of these political parties existed and enjoyed some popularity back in 2000 - such as the Danish People's Party, Italy's Northern League and France's National Front.

But what is very different now is that right-wing populists' bread-and-butter issues have become mainstream.

Socially acceptable

This, following a toxic shock to the European public - made up of the current migrant crisis and the 2008 economic downturn which fuelled the euro crisis.

Questioning (while not always decrying) immigration, integration, the euro, the EU and the establishment, while promoting a stiff dose of nationalist sentiment, is now entirely "salonfaehig", as German-speakers would say.

This literally means "passable for your living room", or socially acceptable.

And something else has been spreading throughout Europe.

Dissatisfaction, cynicism and outright rejection of traditional political parties (as well as business and banking elites), many of which have been in power in Western Europe in one way or another since the end of the World War Two.

This, and not far-right fervour, is arguably driving voters to stage ballot-box protests or to seek alternative political homes - to the delight of Europe's populist parties.

Greece's Neo-Nazi Golden Dawn cannot be lumped with Britain's anti-establishment UKIP

But they vary enormously in their political make-up from far left, to far right, to right-wing populist. They have different values and objectives.

Neo-Nazi Golden Dawn in Greece cannot be put in the same political basket as anti-establishment UKIP, which campaigns for the UK to leave the EU.

Lumping these parties together as evidence of the rise of the far right is simply incorrect.

We also do not know if Mr Hofer will be voted Austria's president after a second ballot next month.

France's National Front has often flopped at the last hurdle in presidential and regional elections.

More accurate than a warning "to heed a wake-up call on the far right's march across Europe" would be to heed a wake-up call that Europe and many of its citizens are floundering and trying to find a voice.

Right-wing nationalism in Europe - a snapshot

In Austria, for the first time since World War Two neither of Austria's two main centrist parties made it to the presidential run-off

Denmark's government relies on the support of the nationalist Danish People's Party and has the toughest immigration rules in Europe

The leader of the nationalist Finns Party is foreign minister of Finland, after it joined a coalition government last year

In France, the far-right National Front won 6.8 million votes in regional elections in 2015 - its largest ever score

The far-right Jobbik party - polling third in Hungary - organises patrols by an unarmed but uniformed "Hungarian Guard" in Roma (Gypsy) neighbourhoods