Verdun: France's sacred symbol of healing

- Published

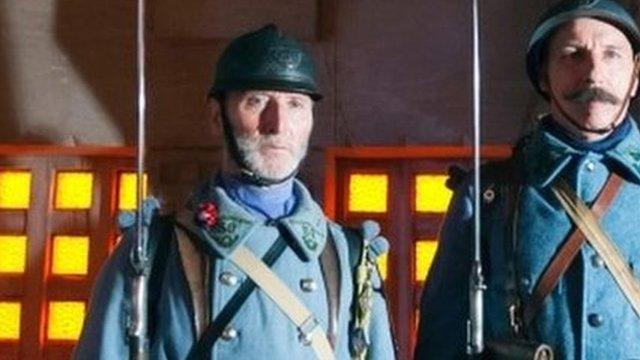

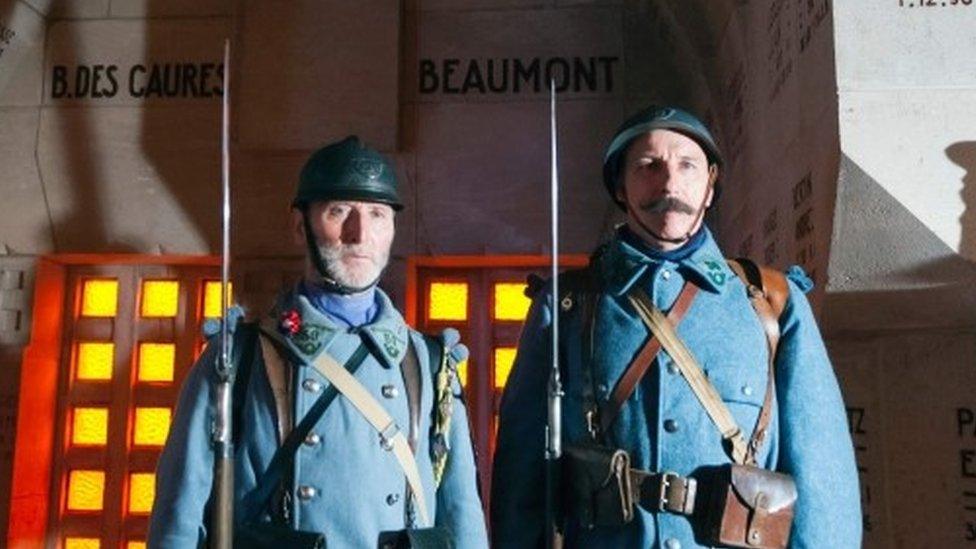

French troops faced sustained bombardment

The British have the Somme. For the French it is the 10-month battle of Verdun.

For both countries, these two epic confrontations came to symbolise the suffering and endurance of the common fighting man.

What is often forgotten, though, is how closely the two battles are connected in the history of World War One.

Because each country sacralised one of the battles - making it the focus of national commemorations - each also tends to overlook the other.

And yet the stories of the Somme and Verdun - the centenary of which will be officially marked in France on Sunday - are tightly intertwined.

Over the winter of 1915-1916, the allies agreed their best hope of beating back the Germans on the western front was to hold off from any offensive action over the spring - but to prepare for a co-ordinated attack in early summer.

Unfortunately these plans were immediately dealt a blow, because the Germans decided to get in first. On 21 February they launched their mass attack on Verdun.

Why Verdun?

Troops had to cope with appalling hardship

The town lies on the river Meuse in north-east France. After 1871 - when the Prussians annexed Alsace and much of Lorraine - it was only a short distance from the German frontier.

Certain that a new war would one day break out, the French transformed the town with a mass of perimeter defences. In the hills overlooking the Meuse, they built 21 vast semi-underground concrete forts, capable of housing 70,000 troops.

In the fighting of 1914 that settled finally on the long western front, Verdun - with its strong defences - was avoided by the Germans.

But that meant it stuck out like a spur into their positions. Should they take the town, it would shorten the German line and greatly strengthen their defence.

On the morning of 21 February, the Germans launched their attack from the north with a mass artillery barrage - the dreaded Trommelfeuer.

Over the next days their troops made steady progress, but the French put up a stout defence - and gradually the advance was stopped.

Attritional warfare

And so began the months of ghastly attrition as the two sides battled it out for a few square miles, pounding each other with cannon, then scrambling forward with bayonets and grenades, gas and flame-throwers.

The fighting was in the hills two to three miles to the north of Verdun, and at the furthest point of their advance the Germans took three of the massive forts: first Douaumont, then Vaux and Thiaumont.

But the French clung on - and as the months passed, the legend of the heroic defence began to take form.

A road - the famous Voie Sacree (sacred way) - was converted into a vital military conduit, ferrying thousands of men and tonnes of material in a constant two-way stream.

Marshal Philippe Petain, then a general and in command at Verdun, organised a system that was dubbed the "noria" - or waterwheel - under which divisions from the whole of the French army were rotated through.

It meant that vast numbers of French soldiers fought at different times at Verdun. Afterwards, this was a crucial factor in concentrating the national memory.

All the while, parliamentarians and newspapers in Paris were turning Verdun into a sacred cause. Any surrender was unthinkable.

Marshal Petain (second right) visiting Verdun after the hostilities had ended

Although it made greater military sense to withdraw to the west bank of the Meuse - and use the river as a line of defence - this was deemed unpatriotic.

So the soldiers fought with the river to their backs.

Meanwhile 150 miles to the west, preparations were proceeding for the Somme - though now with Verdun as a complication.

Initially Petain wanted the Somme to be cancelled, because he said French troops were needed more urgently at Verdun. Later he saw the offensive as an essential diversion, to draw Germans away.

In the event, the French were obliged to scale back massively their contribution to the Somme - from 44 divisions to 14 and from 1,700 artillery pieces to 540.

It meant the objectives on the Somme were also made less ambitious. Of course, as we know, the Germans withstood the allied bombardment and advances at the Somme were pitiful.

But in one sense, the push achieved its aim. Fearful that the German third line at the Somme was about to crack, Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn ordered the transfer of German divisions from Verdun.

The battle of Verdun

Verdun - a strong point on the long frontline dividing the French and German armies - was the longest battle of World War One

At the end of the bloodshed, France emerged as the victor, by December 1916 winning back nearly all the territory it had lost in February

General Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the General Staff and Germany's principal strategist, targeted Verdun because of its position on the Allied line and its sentimental value to French people

Falkenhayn hoped to combine the Verdun offensive with a U-boat offensive against British shipping. The two campaigns together should have brought France and Britain to terms

But Falkenhayn's plan for an attack that would economise on German resources failed to work out as he expected. He used many more divisions than planned

Germany, like France, accumulated huge losses and gained little territory, leading it to throw more and more men into the conflict: Verdun soon became a battle of prestige for the Germans, as well as the French

The fighting continued at Verdun until December. But from July - largely thanks to the British, Commonwealth and French attacks along the Somme - there was no longer any danger of it falling.

Over the rest of the last century, Verdun became the altar of France's remembrance. A vast necropolis was built to house the bones of the dead. It is thought each side lost around 350,000 soldiers.

Verdun also became the symbol of European reconciliation. Chancellor Helmut Kohl and President Francois Mitterrand held hands there in 1984 and on Sunday, Francois Hollande and Angela Merkel will speak again of their shared European vision.

Francois Mitterrand and Helmut Kohl hold hands in a famous gesture of reconciliation

For the UK, the Somme centenary on 1 July will be this year's main World War One moment. For British, Irish and Commonwealth families, it is the Thiepval memorial and the poppy fields that captured the collective memory.

In both countries, the need for a single transcendent focus has obscured wider appreciation of the history of the war.

But 100 years on, there is still much to learn.

- Published21 February 2016

- Published21 February 2016