Switzerland's forgotten role in saving World War One lives

- Published

The first trains carrying wounded prisoners of war to Switzerland were welcomed by cheering crowds

Two of the bloodiest battles of World War One, Verdun and the Somme, are being marked 100 years on, but in Switzerland, centenary commemorations are taking place for a far less known wartime event.

The first contingent of wounded British soldiers arrived on 30 May 1916 for internment in the tiny village of Chateau d'Oex.

Between 1916 and 1918, Switzerland accepted 68,000 sick and injured soldiers: French and German as well as British.

Under the agreement of the warring parties, and with the help of the Red Cross, they were transferred to Swiss mountain villages to recover, and to sit out the war.

Swiss children sang for the wounded soldiers as they arrived

It was, says Swiss historian Cedric Cotter, a pragmatic solution welcomed by all sides. "A lot of the prisoners needed medical care, but there weren't enough doctors in the POW camps, they were all at the front taking care of their own soldiers."

And, he adds, it was a chance for Switzerland, surrounded by belligerents at the time, to show that its neutrality could be useful. The example of neutral Belgium, invaded by the Germans in 1914, had shocked the Swiss, and for two years the government had, according to Mr Cotter, been trying to find policies that would keep the country safe.

"Humanitarian action {became} an important tool of Swiss foreign policy," he says.

Remembering World War One

But amid all the wider European events commemorating the centenary of the Great War, what happened in Switzerland might have been forgotten had it not been for Chateau d'Oex resident Guy Girardet, who began to wonder about a plaque in his local village church.

"It says 'In memory of the British soldiers who were interned in Switzerland from 1916 to 1918'," he explains. "And I was intrigued, what were they doing here in the First World War, and why does no one know anything about it?"

Mr Girardet began doing some research, and uncovered a dramatic tale. When the first train carrying wounded prisoners crossed the border into Switzerland, he learned, the rail tracks were lined with cheering Swiss citizens.

"There was a band at the station in Montreux," says Mr Girardet. And by the time the train arrived in Lausanne, "thousands of people were waiting, throwing flowers into the carriages".

Internees arriving at Chateau d'Oex were given flowers and other gifts

On that train was Susie Kershaw's grandfather, Cyril Edward Joliffe, a captain in the Cheshire Regiment, who had been severely wounded in 1914, and had spent two years as a prisoner of war, being shunted from one German military hospital to the next.

"When he entered Switzerland, he was on a train with 27 officers and 304 men," says Susie Kershaw.

"They were completely overwhelmed by the kindness and welcome they received. He was on crutches by then, he wasn't ever really able to walk again properly."

Captain Joliffe (top L) went on to have three children, but he never fully recovered from his wounds

Britain's ambassador to Switzerland at the time, Sir Evelyn Grant Duff, went to Chateau d'Oex to welcome the British soldiers, and wrote in his diary that evening: "It is difficult to write calmly about it for the simple reason that I have never before in my life seen such a welcome accorded to anyone, although for 28 years I have been present at every kind of function in half the capitals of Europe. At Lausanne some 10,000 people, at 5am, were present at the station.

"Our men were simply astounded. Many of them were crying like children, a few fainted from emotion. As one private said to me: "God bless you, sir, it's like dropping right into 'eaven from 'ell."

Curiosity and compassion

But why were the Swiss so very welcoming? The country was poor, and suffering food shortages because of the war, but its population of just four million was apparently delighted to accept 68,000 seriously injured young men, all of them requiring accommodation, food, and medical attention.

"I think they really wanted to help," says Cedric Cotter, "but there was also a certain amount of curiosity. People didn't have TV of course, so the only news they got of the war was from newspapers.

"But when they saw the internees, for some it was their first view of people that had lost a leg, an arm, some with a face totally destroyed, some so shocked they couldn't speak anymore. So they could realise how terrible the war is."

Tourism boost

But there was another reason too: the start of World War One had virtually destroyed Switzerland's tourism industry. The traditional guests from Britain and Germany were simply no longer coming.

When Alpine resorts heard that the Swiss government was planning to build barracks for the internees, they offered to house them in their own empty hotels.

A propaganda postcard shows Switzerland as a beacon of hope for refugees, POWs and orphans

"They actually competed to host the soldiers," says Guy Girardet. "The reason Chateau d'Oex got the first contingent of British soldiers was because its letter [to the Swiss government] arrived first."

This was more than just an act of charity: the British, French, and German governments were paying for the upkeep of their soldiers.

While no-one got rich out of Switzerland's internee programme, Guy Girardet believes that for many hotels it made the difference, during the war, between survival and bankruptcy.

And so thousands of wounded soldiers were sent, not just to Chateau d'Oex, but to Verbier, Zermatt, Murren, and many other now well-known resorts.

The good food, mountain air, and peaceful surroundings were beneficial, but the return to health of so many young men caused a problem: boredom.

"Verbier is a tourist resort now," points out Cedric Cotter, "but in 1916 there was practically nothing, not even a pub."

The Swiss soon decided that parents, wives, and fiancees would be allowed to visit.

One young woman, Connie Kirkup, writes of getting lost on the long journey across Europe, and then arriving in the Alps to find her fiance Angus, well recovered from his injuries, taking part in a bobsleigh race: "My heart stood still, but oh it was great - and the English team won!"

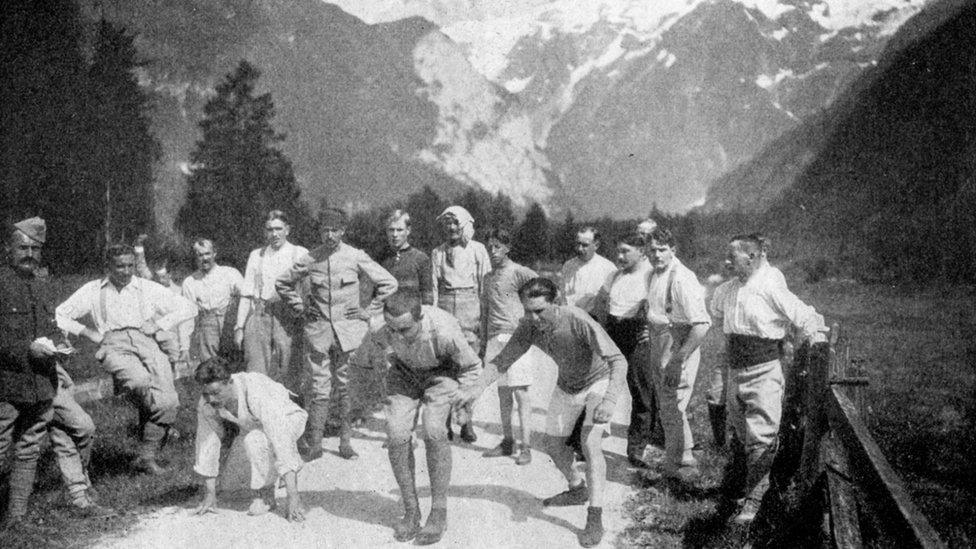

When they were well enough, internees took part in sport to alleviate the boredom

Susie Kershaw's grandmother, Millicent, arrived in Chateau d'Oex in June 1916 to visit her husband Cyril, and, as Susie has just learned, her visit became more permanent.

"What we have is a [Swiss] baptism certificate for her first baby, dated May 1917, my uncle Geoffrey. So she stayed," she explains.

Her grandfather never fully recovered from his war injuries, dying in 1931 aged 48. But Susie Kershaw believes the transfer to Switzerland was of considerable help: "He had three children afterwards. Perhaps I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for that."

One hundred years on, historian Cedric Cotter believes the welcome for so many wounded prisoners of war paid political dividends for Switzerland, encouraging its European neighbours to view its neutrality in a more positive light.

He suggests it even influenced the decision to use Geneva as the base for the new League of Nations, and ultimately the European headquarters of the United Nations.

- Published28 May 2016

- Published8 January 2016

- Published19 June 2023