Migrant crisis: Bulgaria tightens border with Turkey

- Published

Has Bulgaria become the new route of choice for migrants trying to enter Europe?

Bulgarian officials hope a new agreement with Turkey will prevent their country becoming the main land route for migrants heading to western Europe.

The deal between the two countries is a result of another agreement between the EU and Turkey, reached in March, that aimed to slow down the number of people arriving into Europe in the first place.

The newer deal has had a knock-on effect on anyone hoping to cross from Turkey into Bulgaria.

Any migrants who manage to get through or round a 146km (90-mile) fence, almost finished on the countries' 260km border, will now be sent to a purpose-built camp at Pastrogor, in south-east Bulgaria.

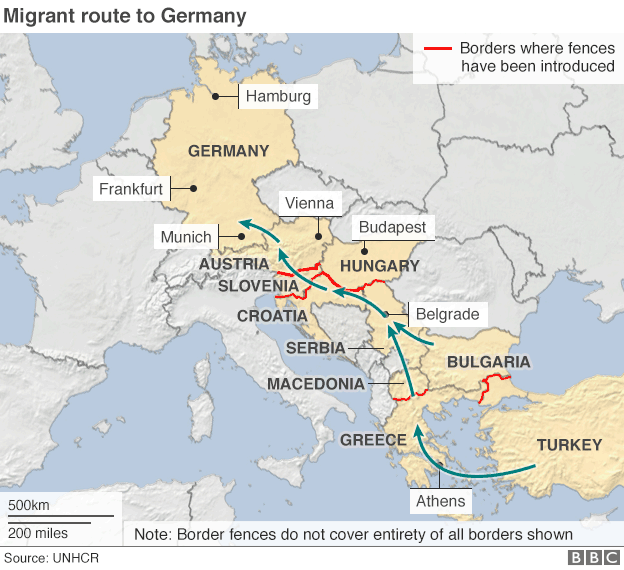

This section of the border is getting attention for a reason: the EU-Turkey deal largely cut off the Greece-Macedonia route, so people smugglers have been seeking new routes, or reactivating old ones.

In the hands of smugglers, migrants disappear after entering Europe and resurface only briefly - in Sofia and the Serbian capital Belgrade.

Migrants in Sofia: Nearly all dream of a future in richer parts of the EU

Between 200 and 400 have been arriving daily further north in Austria since the beginning of the year, after crossing Hungary.

At the weekly video conference calls of all countries involved, Bulgarian and Macedonian officials quarrel over who is letting them through.

The Bulgarians say "only 50" a day are smuggled through Bulgaria, an EU member since 2007. Another - Serbian - source suggests the number is closer to 200 a day.

The new razor-wire border fence is a major obstacle for migrants trying to cross from Turkey

All that matters to western European officials is that the numbers are now regarded as manageable, and proof that the much-criticised EU-Turkey agreement, external is holding for the time being.

If Bulgarian authorities can produce convincing evidence that migrants came through Turkey - bus tickets, currency, biscuit wrappers - they can be returned within five days, or 12 days if they appeal against extradition and if their asylum request is rejected by Bulgaria.

"If this agreement actually starts working and we can very quickly return the migrants to the Turkish side, we think this will discourage the majority of them to pay traffickers to be trafficked through the border," says Bulgarian Deputy Interior Minister Philip Gounev.

And whether it works will depend entirely, as with the EU-Turkish agreement, on Turkish goodwill.

"Regardless of what the agreement says, regardless of the protocols and the deadlines we've set, unless there is goodwill to process and to quickly return the migrants, there are always ways to delay and make the return very difficult," Mr Gounev tells the BBC.

The UK donated these vehicles to the Bulgarian border police

Tourists, goods - and migrants?

Along the Bulgarian-Serbian border more than 100 foreign, mainly Austrian and Hungarian, police are being drafted in to reinforce their Bulgarian colleagues, under the auspices of the EU border force, Frontex.

There is little sign of them here in the northwestern corner of Bulgaria, near the city of Vidin. A new bridge over the Danube here, to Romania, was opened three years ago. It was advertised as the missing link in what will become "the main tourist and goods route between western Europe and the Middle East".

Europe's police forces are anxious that it does not become the main migrant route too.

On the gently rolling hills beside the villages of Bregovo, Rakitnitsa and Kosovo, peasants tend their vines and try to repair the dilapidated homes their children and grandchildren left long ago, to seek their fortunes in Germany. This is a landscape scarred by emigration long before the current wave.

Most migrants entering Bulgaria now are Afghans - far fewer Syrians are coming in than previously

According to official figures, 80% of migrants crossing Bulgaria now are from Afghanistan. Another 10% are Iraqis, and there are almost no Syrians - another sign that Turkey is keeping its word.

Near the Lion's Bridge district of Sofia, where many migrants living in refugee camps or cheap hostels congregate each evening, one man tells me his experience at the hands of smugglers.

"Before the border we jumped out of the car, and walked in the jungle, for three to five hours, to Serbia. But the Serbian police caught us and sent us back to Bulgaria."

Back in Sofia, he was detained for three weeks, then put in an open camp. In a few days, he says, he will try again.

His dream is to get back to Birmingham, where he once lived - "my city", he laughs, though he has an Arsenal Football Club tattoo below his right ear.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published24 May 2016

- Published11 April 2016

- Published30 March 2016

- Published6 December 2015