Turkey tourism: an industry in crisis

- Published

No fights necessary over sun beds at hotels in Antalya

The group of British tourists playing water polo in the pool could shriek as loudly as they liked: there were virtually no other guests they'd disturb.

The four-star Garden Resort Bergamot Hotel in Kemer, just outside Antalya, should be 70% full at this time of year. But just 25 of the 233 rooms are taken.

"We've had to reduce our staff from 80 to 50 and prices have dropped by a third," says Suha Sen, the owner.

"If it goes on like this next year, we may have to close."

Around the pool, the few guests soaking up the sun say they clinched bargains.

"We paid just over £500 (€630) for two of us for a week, an all-inclusive package," says Diane Roberts from North Wales. "Most of the cheap deals now are for Turkey - we didn't expect it, but people are too afraid to come here."

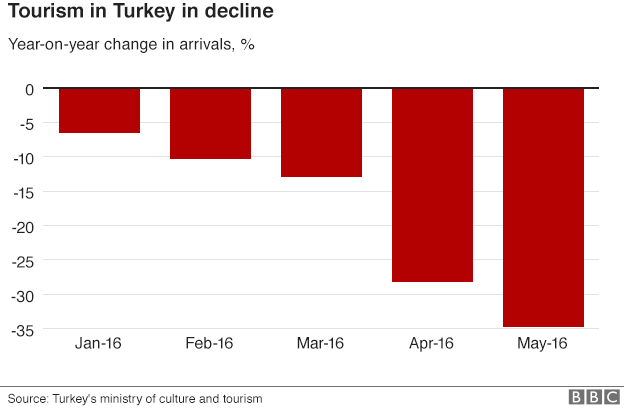

It is a picture repeated across Antalya and throughout the country: Turkish tourism is in crisis. A country that welcomed 37 million visitors in 2014 - then the sixth most popular tourist destination in the world - is expected to see a drop of at least 40% this year.

Amid the downturn, tourists are being offered cheap deals for holidays in Turkey

A former hotspot for Russian tourists now empty - the Delphin Imperial in Antalya

The main decline is the Russian market, the four-and-a-half million Russian tourists who were coming have fallen in number by around 95%. The trigger was Turkey shooting down a Russian military jet which violated Turkish airspace last November, sparking a diplomatic crisis between the two countries.

The Kremlin seethed, barring Russian tour companies from selling package deals to Turkey. President Vladimir Putin told Russians to holiday elsewhere.

The two strongmen leaders - Mr Putin and his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan - are still at loggerheads, although Mr Erdogan did send a note to his counterpart this week to mark Russia's national day, in the hope of healing wounds.

What's more, a series of bombings across Turkey in the past year has scared off many others. Since violence resumed with the PKK Kurdish militants last summer, attacks by them and by the Islamic State group have occurred nationwide, some targeting tourists in Istanbul.

Tensions between Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (pictured) and Russian President Vladimir Putin has led to a steep decline in Russian visitors

British and German visitors are down by a third.

Political instability, with a president who makes the headlines for lambasting the West, prosecuting critics and labelling birth control "treason", hasn't helped.

It's not just the 8% of the workforce directly employed in tourism that are affected but also those that depend on the custom from foreign visitors.

In the old town of Antalya, shopkeepers sit idly in front of their businesses in the hope of passing trade, which simply isn't coming. Bright bougainvillea is draped over stone shops selling carpets and leather bags. But the streets are quiet.

Jewellery shop owner Istiklal Sevuk says President Erdogan is hurting Turkey's image

Repeated terror attacks on major cities in recent months have played an important part in deterring tourists

Istiklal Sevuk has run his jewellery shop for almost 30 years and says it's never been so bad. "Yes we have terror attacks in the main cities - but our biggest problem is our government and President Erdogan," he says.

"He doesn't follow peace with our neighbours and he's damaging the image of the country. We don't have a government anymore - we have one man who does everything. Erdogan is why we're in this mess."

Mr Erdogan has blamed the rebel Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) for Turkey's current instability and rejected Western criticism of his policies.

In the once Russian-dominated area of Belek, businesses have been crushed. One tour operator, Pegas, used to bring 19 planes a day to Antalya, full of Russians. Now the company has had to ditch the fleet and fire 3,000 staff.

Tourism is at 'rock bottom', Delphin Imperial hotel director Tolga Comertoglu says

Geo-political and security factors are both responsible for the decline in Turkey's tourism

At the flashy Delphin Imperial hotel and private beach, where Russians used to flock, it's hard to hear a word of Russian spoken.

The place screams lavishness, from the design - modelled on New York's Chrysler Tower - to the giant crystal chandelier in the lobby to the neo-Baroque gold-plated furniture.

But wealthy Russians are staying away and it's less than 40% full.

Its director, Tolga Comertoglu, is also on the board of the Antalya Hotel Association. With dyed blonde hair and tight-fitting suits, he fits into the Delphin's eccentric style. And he says he's deeply worried about the empty beaches, which he scans from above in his private helicopter.

"My family has had 40 years in tourism and I've never seen it like this", he says. "We've hit rock bottom - I don't want to think what will happen if it gets worse."

And then what, I ask?

"It could mean the whole tourism sector could virtually end here," he says. "And that means minus $28bn."

Claire Smith, from Blackpool, says tourists shouldn't be scared off by terror attacks in Turkey

Strolling through Antalya old town is an English couple from Blackpool, Mark and Claire Smith. The souvenir shopkeepers jump on them - but today they're not buying. "It's incredibly sad to see what's happening," she says. "Turkey is such a wonderful country but people aren't visiting. How can they survive?"

I ask whether they had concerns about booking here. "My husband plays golf with someone who said 'oh I wouldn't go to Turkey right now'. So he went off to Orlando instead. And look what happened there! We have to come - or the terrorists will just win."

On the quiet beaches of Antalya, the June sun has warmed the Mediterranean, the sand is soft and the mountains silhouetted in the distance give a picturesque backdrop.

But the tide of tourism has turned in Turkey - and with attacks continuing and an increasingly unpredictable president, there's little sign of improvement on the horizon.

- Published22 August 2023

- Published25 April 2016