WW2 Jewish escape tunnel uncovered in Lithuania's Ponar forest

- Published

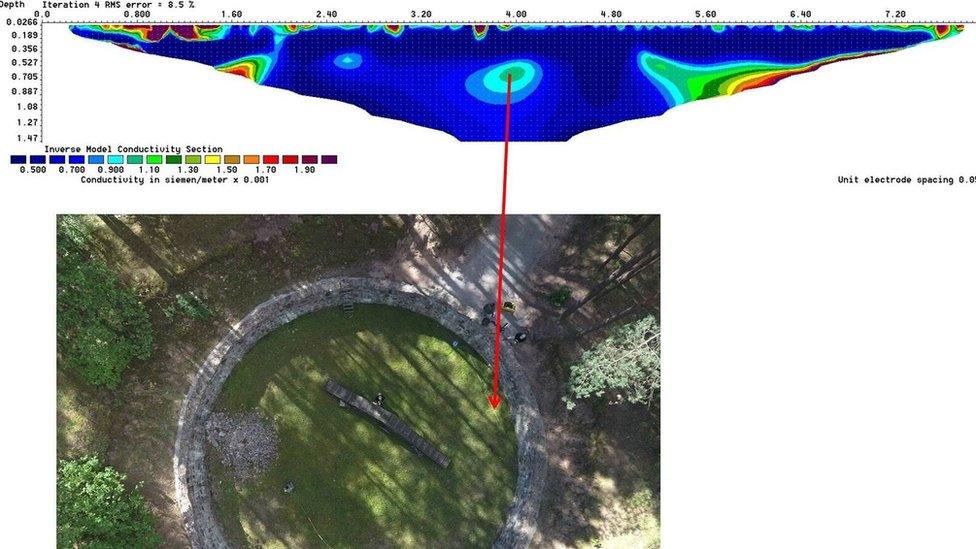

Prisoners dug the tunnel in a pit they were kept in

A tunnel dug out with spoons by Jewish prisoners escaping Nazi captors in World War Two has been uncovered in Lithuania's Ponar forest.

The prisoners were from the so-called Burning Brigade, who were forced to burn corpses to cover up Nazi atrocities as the Soviets advanced.

Knowing they too would be killed, they dug a tunnel in a pit where they were kept. Eleven escapees survived the war.

A research team used a ground-scanning system to map out the tunnel.

The exact location of the 34m (112ft) tunnel had been lost since the end of the war, but the international team, including the Israel Antiquities Authority and researchers from the US, Canada and Lithuania, have now located it.

The team employed the electrical resistivity tomography system, also used in oil exploration, so as not to disturb any human remains at the site.

'Yearning for life'

Ponar forest, known now as Paneriai, is outside the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius, a hub of Jewish life before the outbreak of the war.

But under Nazi occupation, mass burial pits and graves were carved out of the forest to hold the bodies of up to 100,000 people, including 70,000 Jews, killed during the Holocaust.

As the Red Army closed in, the Nazis tried to cover up their atrocities. They forced about 80 prisoners from the Stutthof concentration camp, chained by the legs, to dig up bodies and burn them.

Ground scanning was used to pinpoint the tunnel

The scanning was used so as not to disturb any human remains at the site

They were called Leichenkommando (corpse unit), but later became known as the Burning Brigade.

According to one account, one brigade prisoner even identified his wife and two sisters among the bodies.

Kept overnight in one of the pits where the bodies had been buried, the prisoners began to dig a tunnel and on the night of 15 April 1944, 40 made their escape attempt through the 2 sq ft tunnel.

But guards were alerted by the noise and hunted them down. Many were shot but 12 escaped to reach partisans. Eleven survived the war to tell their story.

Jon Seligman, of the Israel Antiquities Authority, said he was reduced to tears on the discovery of the tunnel, calling it a "heart-warming witness to the victory of hope over desperation".

"The tunnel shows that even when the time was so black, there was yearning for life within that," he told Associated Press.

Archaeologist Richard Freund, also on the team, told the New York Times that Ponar was "ground zero for the Holocaust", evidence of systematic murder before the Nazis started using gas chambers.

- Published15 December 2015

- Published24 March 2014