Will Dutch follow Brexit with Nexit or stick to EU?

- Published

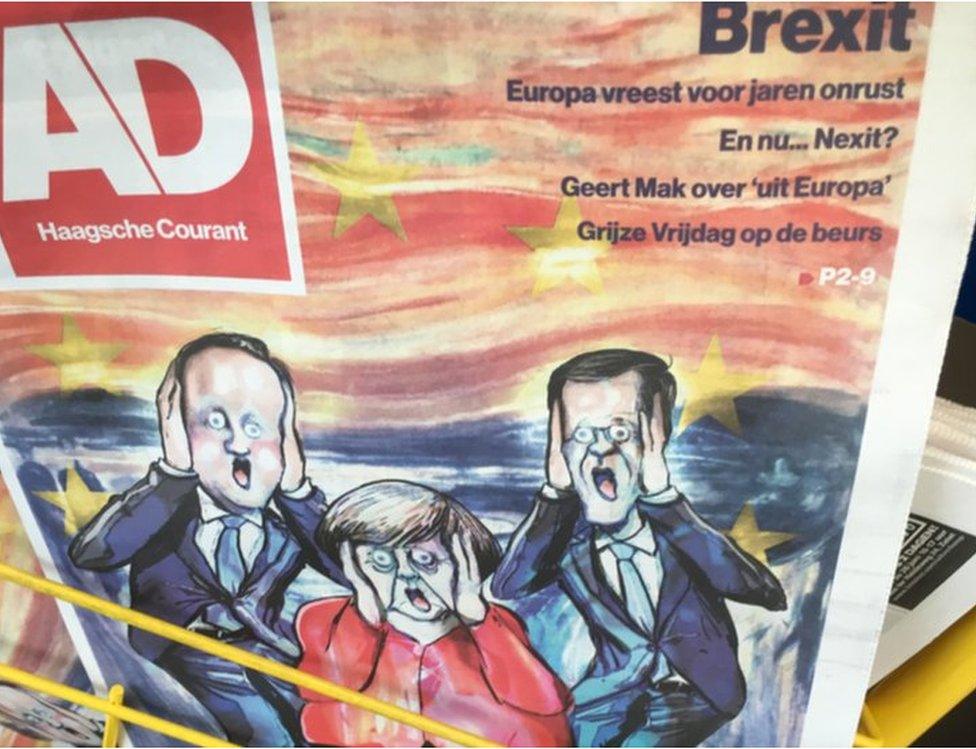

The front page of Dutch daily Algemeen Dagblad showed European leaders fearing for the future after Brexit

The fallout from Brexit has sent ripples of apprehension across the North Sea. And it has given rise to the question, could the Netherlands be next?

Geert Wilders, leader of the Eurosceptic Freedom Party, was among the first to congratulate his colleagues across the North Sea for securing their "Independence Day".

There are shared concerns about European immigration and Brussels bureaucracy among the Dutch electorate.

And yet, "Nexit" is by no means inevitable.

In fact, according to the rules of the Advisory Referendum Act there is no legal possibility of holding a vote on the Netherlands' membership of the EU. Referendums can cover only new legislation and treaties, and are only advisory.

The only way to hold a Nexit vote would be to change existing legislation, and that is only likely to happen if Mr Wilders wins elections next year.

Geert Wilders' Freedom Party leads Dutch opinion polls and wants his country to follow the UK's example

"Our interests in the internal market are even larger than the UK's interests," Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem told the BBC outside a sun-drenched Dutch parliament.

The Brexiteers were living in their own world, he said, arguing that the Dutch were more conscious of what was at stake, with 80% of national exports heading to the rest of the EU.

"Certainly here in the parliament there's hardly any support for a referendum. A strong majority of the Dutch feel as though we should be inside the EU, reform it, make it better. We would have liked to have done it with the British.

"There's also very little support among our people, very few have the appetite for this kind of referendum."

Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem says there is little support for a Dutch referendum

Most recent polls suggest a slight majority of voters oppose the idea of an in-out Nexit vote. A Maurice de Hond survey suggested that 53% were against a referendum.

"We don't see the EU as a threat as a big imperial monster, we see it as something you can negotiate with," says Hans Steketee, editor of the NRC Handelsblad newspaper.

"It's like Brussels sprouts, you might not like them but you eat them because you know they're good for you. My gut feeling is that people will say: 'Oh well, if this is what happens after Brexit we should definitely think twice.'"

Nestled in a booth in a cosy cafe beside an Amsterdam canal, prominent Eurosceptic campaigner Thierry Baudet warns me of a deliberate and cynical attempt by European politicians to punish the UK to prevent others from following suit.

"Do they really think this is the way to keep countries in? By scaring and fighting Britain?" says Mr Baudet, one of the key instigators of an April referendum in which Dutch voters rejected an EU trade deal with Ukraine.

Hans Steketee explains why the Dutch are unlikely to see a referendum

"It'll backfire sooner or later. It's not a position that's sustainable in the long run."

The real consequences here are unlikely to become clear until the UK triggers Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty - the mechanism for leaving the European Union.

But with the UK's future inside the European single market uncertain, pragmatic Dutch politicians are seizing on the potential exodus to lure banks and businesses afraid of losing access to the market across the North Sea.

Amsterdam was placed ahead of Dublin, Frankfurt and Paris this week, by the New York Times, external, as most likely to succeed London as global financial capital.

That is encouraging news for Kajsa Ollongren, the Dutch capital's deputy mayor whose message particularly for companies based in Asia and the US is: "If you're in Amsterdam, then Europe is your market."

"That's what's important to companies right now, to have access to the internal market of the European Union. We try as much as possible to be ready. We feel very close to the City of London but at the same time we're competitors."

'Stupid stuff'

However one potential deterrent could be a cap on bankers' bonuses imposed by the Dutch government in 2015.

Prime Minister Mark Rutte has tried to reassure the banking industry, suggesting the cap of 20% of annual salary is "flexible for foreigners".

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte sees eye to eye with the UK's outgoing prime minister

The Dutch cap is far lower than the 100% cap set by the EU in response to public outrage at excessive bankers' pay during the financial crisis.

And Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem appears less keen to remove those limits. "The really big investment banks are driven by a bonus culture, the majority of pay there is bonuses, and I don't see any room for that in the Netherlands," he says.

For Mark Rutte, the fallout from Brexit is personal as he lost a close friend and ally in David Cameron.

They texted regularly - "mostly about stupid stuff," he told me recently.

Many Dutch politicians hope the Eurosceptic rise will halt as a result of the UK vote

And the self-confessed anglophile prime minister took a somewhat softer stance than other European leaders over Brexit, arguing that Britain should not be rushed, given the country had "collapsed - politically, economically, monetarily and constitutionally".

That message was perhaps partly to his own electorate - suggesting they should be careful what they wish for.

Ahead of parliamentary elections in 2017, Brexit has presented him with a valuable opportunity to show what the Netherlands has to gain from remaining in the EU.

Instead of spawning referendums elsewhere in Europe, the UK vote could serve to counter the Eurosceptic rise in the Netherlands, France, Sweden and elsewhere.

But with eight months before the Dutch election, there is plenty of time for the tide to turn.

- Published6 July 2016

- Published4 July 2016

- Published29 June 2016

- Published6 July 2016