Why jihadists stalk the French Riviera

- Published

It is not yet clear if the Bastille Day attack has Islamist links, but Nice has become a breeding ground for jihadists

The French Riviera is a renowned playground for the cosmopolitan elite, but what is less well-known is that it is also a breeding ground for jihadists.

Move a mile or two from the Nice coastline and its marinas, and you find bleak housing estates where disaffected youths of immigrant origin are vulnerable to radical Islam.

In recent years, 55 people are estimated to have left the region for Syria, including 11 members of the same family travelling together in 2014.

In terms of reported cases of radicalisation, the Alpes-Maritimes area is second only to the notorious "93" district north of Paris.

Imene Ouissi, a 22-year-old student who volunteers for a women's group in the town of Vallauris, west of Nice, noticed in 2012 that local youths were becoming fascinated by slick recruitment videos produced by Islamic State.

For three years, many people flocked to hear a preacher at a make-shift mosque among these flats in the town of Vallauris, until the authorities dismantled it

"It was better than a film. It made them dream," she says. "In gaming you can shoot again and again, but this was real. And you can do that for God! They found it fantastic."

'You will never succeed here'

At the same time, self-styled preachers emerged with a message targeted at disaffected Muslim youths. Playing on widespread feelings of resentment about poverty and discrimination, they told their audience that they would always be treated as foreigners in France.

In Vallauris, one charismatic figure pitched up in a high-rise housing estate in 2010. People came from all over the region to hear him preach every Friday until, after three years, the authorities dismantled his makeshift mosque.

Student Imene Ouissi says she has noticed a growing fascination for IS recruitment videos among young people in the area

"What he said really shook me," Imene Ouissi recalls. "I had gone there because everyone was talking about it. He spoke the language of the kids, so they identified with him. His message was: you must not stay in a land of villains, you will never succeed here. You must go to a Muslim country."

Kamel, a youth worker in the Nice area, says one of the reasons for the recent success of the Salafist ideology that has inspired jihad, is that it provides a ready and easy way of justifying the actions of petty criminals.

"The kids are told that they are in a land of unbelievers, so when they steal and attack people it is justifiable. The petty criminal is turned into a holy warrior, and is promised status, sexual gratification and eternal life."

At a time when identity feeds on a sense of victimhood, past trauma is often used to stoke current tensions. In the Nice area, Algeria's war of independence in the 1950s and early 60s casts a long shadow.

Many former French colonists who were summarily expelled from Algeria settled in Nice. Their political influence and lingering resentment at the French state that let them down are still felt in the strong presence of the far-right National Front there, Kamel says.

Equally, he adds, crimes committed by the French army during the war are increasingly being dredged up by children of Algerian ancestry to nurture a feeling of alienation. "We have competing identities, and people who want to make others pay for the crimes of past generations."

Fatima Khaldi, a councillor for a tough area of north-eastern Nice, is alarmed by the number of young people who define themselves as Moroccan, Algerian, or Tunisian.

"It's worrying to see third, fourth or fifth-generation children who do not feel French. People like me, who are from the second generation, cannot understand that."

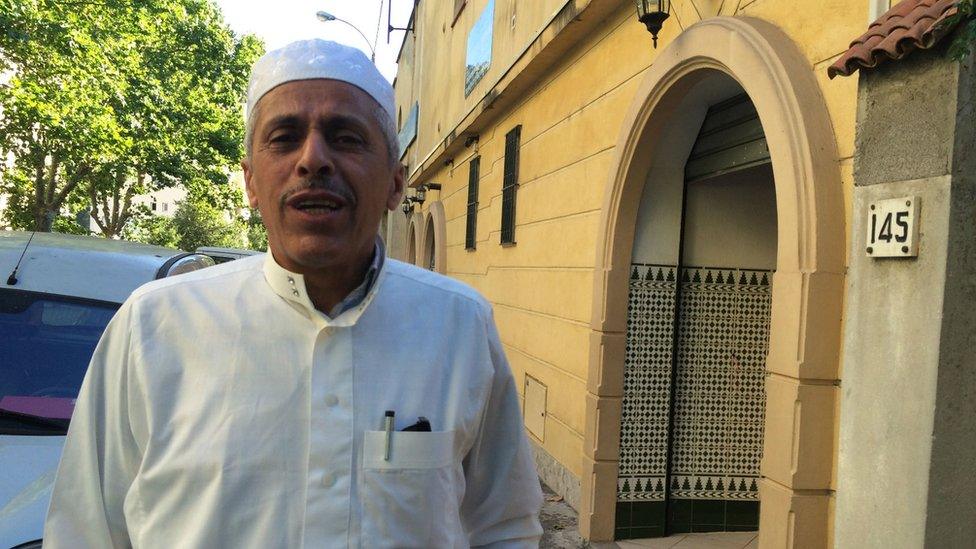

Local Imam Boubekeur Bakri has long been concerned about home-grown jihadists

Boubekeur Bakri, an imam from the same area, says he became worried about the rise of extremism as early as 2010. By December 2014 he gathered local officials and Muslim leaders in his mosque to sound the alarm.

Three weeks later the attacks against Charlie Hebdo and a Jewish supermarket confirmed his fears. He calls radicalism an "open wound" for the Muslim community.

The problem, he says, is that having 40% unemployment "lowers the immunity" of marginalised communities, allowing "microbes" to spread.

Another reason for the prevalence of jihadist ideas in parts of the Riviera hinterland has been the presence of good recruiters. Omar Diaby, a criminal from Nice also known as Omar Oumsen, is believed to have sent about 40 local youths to Syria before settling there himself three years ago.

A few budding jihadists have managed to return to the city. Jean-Francois Fouque is a lawyer for one of them, a troubled youth who went to Syria as part of a group of friends in 2014.

The man witnessed unspeakable violence, including the beheading of one of his fellow French recruits who had complained about IS discipline. He managed to slip out but what he went through will stick with him forever, Mr Fouque says. "He wants others to know. His message is: don't go."

Those fighting radicalisation have for some time been warning that jihad can be fought "here in France with cars and knives"

But as word of atrocities in IS territories spreads and border controls are tightened, most observers believe the main danger is no longer departure for Syria - but conducting the holy struggle at home.

Patrick Amoyel, a psychoanalyst who heads "Entr'Autres", a Nice-based association that helps fight radicalisation, stresses that jihad means an effort to reach out to the House of Islam.

Speaking on a glorious afternoon before the Bastille Day celebrations in Nice, he said: "You can either wage Jihad by the tongue and by the mouth - that is ideological jihad - or by the hand and the sword. Those are the official categories of jihad.

"And jihad by the hand and the sword can be done here in France with cars and knives."