Attack on Nice brings danger to France closer to home

- Published

Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel was a minor offender with no previous background in jihadism

Through the last 18 months of jihadist terror in France, a simple pattern is emerging: it keeps getting worse.

If the January 2015 attacks were aimed at specific groups - Jews and blasphemers - the November follow-up was more indiscriminate.

At the Bataclan and at the cafes the Islamists killed young adults, out being European hedonists.

This time, it's gone a step further.

In Nice, it is the people at large - families and groups of friends - doing nothing more provocative than attending a national celebration. Ten children were among the dead.

So what's next?

As the government contemplates its response to the atrocity, one thing is absolutely apparent. The most comprehensive security set-up in the world will not stop the kind of attack that took place on Thursday.

The danger today is no longer webs of intrigue stemming from the Middle East like the Bataclan, with months of planning, smuggled immigrants and secret flows of cash. Today, the danger is the guy next door.

Will Shore, eyewitness: "You could see the fear in people's faces"

It is your neighbourhood terrorist.

Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel, who carried out the Nice attack, had no background in Islamism. He was a lorry driver with a bad attitude, a flat in town, and some convictions for petty violence.

Hardly a rare profile.

And yet he talked himself into an act of inexplicable savagery, deliberately mowing down his own townspeople in a 19-tonne truck.

The presumption is that he "self-radicalised": in other words he fell prey to the torrent of jihadist propaganda emanating from so-called Islamic State (IS), and elevated his personal grievances into matters of cosmic importance.

Larossi Abballa, who murdered two police officers at their home in Magnanville west of Paris last month, had a similar past.

Grace-Ann Morrow, eyewitness: "It was complete chaos"

Again a nondescript minor offender - no apparent religious leaning - who was transfigured by an act of blood.

What the two had in common was not just a weakness for Islamist ideology. They also had hate: a hatred for France, for its symbols, and for all it stands for.

This is the awful problem facing any French government.

There are many tens of thousands of young Muslim men who feel this hatred for the country that is in theory their own. Normally this is not religious in origin, but increasingly religion is its form of expression.

The Nice attack left families torn apart but was praised by jihadist group IS

The vast majority will not translate the feeling into violence.

But some will, all the more so now, after IS told would-be jihadists to give up the idea of coming to Syria and do what they can at home.

And what Nice, and in a lesser way Magnanville, showed is that a determined killer can always find a way.

Troops on the street, extra checks at railway stations, protection at synagogues - these will prevent attacks at particular places at particular times.

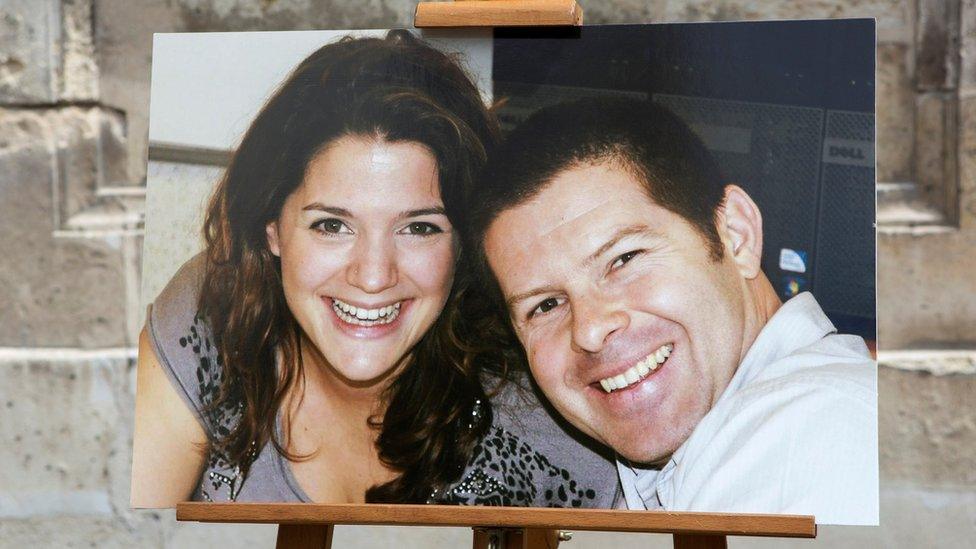

Jessica Schneider and Jean-Baptiste Salvaing were murdered at their home west of Paris by a jihadist wielding a knife

But when a car or a kitchen-knife is a weapon, and when a potential victim is you or me, then there is no stopping the assassin.

Which is why the most gloomy prognostications are probably correct.

What we have seen up till now is not as bad as what is to come.

The next stage in the descent is one that few will talk about - but which is certainly in the minds of both jihadists and government.

This is the moment when the attacks become so outrageous they provoke a backlash. A mosque is burned to the ground. Some white youths go on a rampage through a banlieue (suburb).

This is what IS desperately wants to happen, of course, because France could then be on course for a truly bloody civil conflict.

The head of France's DGSI internal intelligence service gave just such a warning in recent testimony to a parliamentary committee.

The greatest danger, warned Patrick Calvar in May, was that one or two further attacks triggered violence from far-right groups which - he said - were increasingly preparing for the eventuality.

"Then what you will have is confrontation between the far right and the Muslim world. Not with Islamists, let me be clear. With the Muslim world."

In other words, the pattern continues. It will get worse.