Turkey coup: What is Gulen movement and what does it want?

- Published

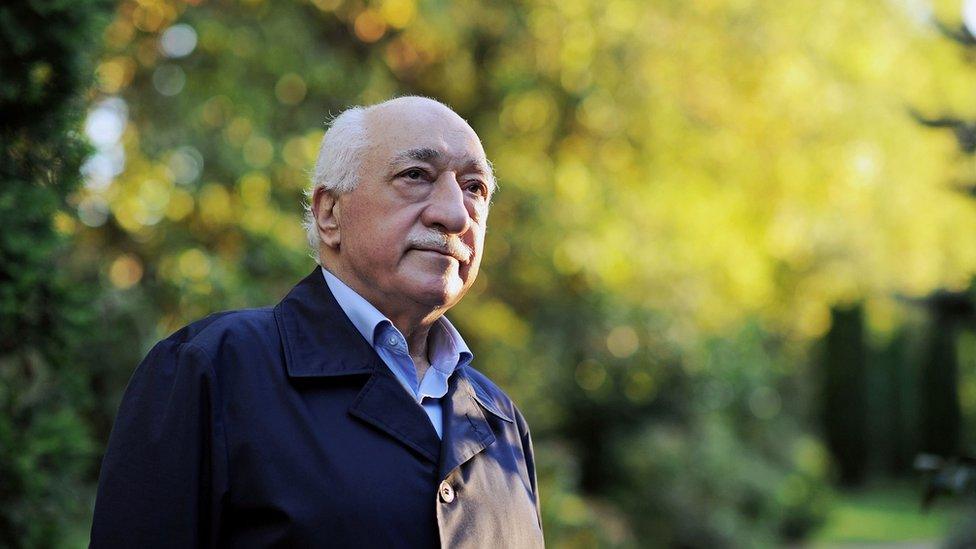

Mr Gulen denies involvement in the coup

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan blames US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen for last week's bloody attempted coup.

Suspected Gulenists are now being purged in their thousands in a wave of arrests and sackings and Mr Erdogan has declared a state of emergency.

But what do we know about the movement, and what does it want?

What is the Gulen movement?

A well-organised community of people - not a political party - named after the US-based Islamic cleric Fethullah Gulen.

He is regarded by followers as a spiritual leader and sometimes described as Turkey's second most powerful man.

The imam promotes a tolerant Islam which emphasises altruism, modesty, hard work and education.

He is also a recluse with a heart condition and diabetes who lives in a country estate in the US state of Pennsylvania.

President Erdogan's supporters don't believe Mr Gulen's denials

Fethullah Gulen: Powerful but reclusive Turkish cleric

The movement - known in Turkey as Hizmet, or service - runs schools all over Turkey and around the world, including in Turkic former Soviet Republics, Muslim countries such as Pakistan and Western nations including Romania and the US, where it runs more than 100 schools.

Followers are said to be numerous in Turkey, possibly in the millions, and are believed to hold influential positions in institutions from the police and secret services to the judiciary and Mr Erdogan's ruling AK Party itself.

How did the movement emerge?

Mr Gulen made a name for himself by arguing that young Turks had lost their way and that education was the best response, a position that attracted a growing number of middle class followers and led the movement to open schools and expand into business.

As the movement grew, followers began taking jobs inside the machinery of state.

Some, such as commentator Mustafa Akyol, external, say the aim was to transform Turkey away from secularism, despite Mr Gulen's claims to be focused more on faith and morality than politics.

After the military coup of 1980, the ruling generals suspected him of trying to topple the government and he was arrested after six years on the run. He was freed but eventually charged in 2000 and decided to remain in the US, where he was having medical treatment.

Exiled cleric Fethullah Gulen condemned the coup attempt as treason

Both Mr Erdogan and Mr Gulen portray themselves as pious Muslims in opposition to secularism - but some see a slight difference in their approaches.

Mr Erdogan is seen as favouring a Turkish version of political Islam, according to Mustafa Akyol, external, while Mr Gulen presents himself as espousing a form of cultural rather than political Islam.

Many say the ultimate goals of the Gulen movement remain unclear.

"I know that their interest in education is not enough for them, they want more, but what?" author Fehmi Koru told the BBC. "I suggested in my columns that they set up their own party and ask for a mandate to run the country. They did not do that."

How did Mr Gulen and Mr Erdogan become rivals?

With their focus on Islamic values, Mr Gulen and his followers were natural allies for Mr Erdogan as he took power.

He first used the Gulenists' bureaucratic expertise to run the country and then exploited their connections to get the military out of politics.

Some say Mr Erdogan wants to impose a form of political Islam on Turkey

In 2010, the big Sledgehammer case began, which led to 300 army officials being jailed for allegedly organising an attempted coup in 2003. Most of the evidence against them was later found to have been fabricated.

Turkish journalist and academic Ezgi Basaran says it is now acknowledged that the trials were orchestrated by Mr Gulen's followers in the military, intelligence, police and judiciary.

Who was behind Turkey coup attempt?

Once the military had been sidelined, Mr Basaran says, a power struggle began to take shape as the AKP and the Gulenists vied for control of the state.

Who is winning that struggle?

"A war between two factions - one in power and the other having only infiltrated the civil and military bureaucracy - is a war whose winner is obvious from the start," says Mr Koru.

Having dispatched the military, Mr Erdogan went after Hizmet in 2013 by vowing to shut down thousands of private schools that prepare students for exams, about a quarter of which were run by the Gulenist movement.

He also began attempting to force people believed to be Gulenists out of the security services and government ministries, which he said constituted a "state within a state".

Observers say Mr Erdogan has won the power struggle with Mr Gulen

Shortly afterwards, however, Turkish police carried out dawn raids against leading businessmen and allies of the prime minister.

They were alleged to have helped Iran bypass international financial sanctions against it by sending the regime in Tehran gold in return for oil and natural gas.

Turkey's PM Erdogan faces threat from wounded ally

Many believed Gulenists were behind the raids and Mr Erdogan is said to have become convinced that a "Gulen-Israel axis" was out to get him, the Economist, external reported.

In May 2016, the Turkish government formally declared the Gulen movement a terrorist organisation.

How does the failed coup fit into this?

Mr Gulen has denied any involvement in the attempted coup and suggested Mr Erdogan himself may have been behind it, given the wave of arrests that has followed.

Turkey's coup attempt: What you need to know

Cleric Gulen condemns post-coup 'witch-hunt'

However, analysts have suggested that the coup authors - whether Gulenists or secularists - may have brought forward plans because they suspected Mr Erdogan was about to purge the military anyway.

Soldiers involved in the coup surrendered after a night of violence

The sheer numbers of arrests - almost a third of the military top brass as well as thousands of officials and bureaucrats - suggests that Mr Erdogan did already have lists of targets.

Turkey has now requested Mr Gulen's extradition from the US to face trial but the US has said it will need to see evidence of Mr Gulen's involvement first.