Is Angela Merkel's political capital running out?

- Published

After an embarrassing regional electoral defeat, and with her approval ratings slumping, is Angela Merkel's political capital running out?

Late summer in Berlin, flat barges drift along the river Spree, ferrying the last of the season's tourists. A guide gestures up at the chancellery: "Angela Merkel works here," and smartphones are pointed, poses struck.

Shielding their eyes against the sunshine, the visitors look up at the bright white stone and glass building in front of them. Perhaps a few of them notice that the ivy that spreads across its outer walls is just starting to turn red.

Angela Merkel is in for a turbulent autumn.

Her approval ratings are at a five-year low, and she is smarting from a humiliating regional election result, in which her conservatives (CDU) were beaten into third place by the surging anti-Muslim party Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Germany is on edge - horrified in part by the rise of the right and unnerved by the arrival of well over a million people seeking asylum and what appear to have been two attacks by asylum seekers inspired by the so-called Islamic State.

And as far as many, including some of her own party, are concerned, Mrs Merkel and her refugee policy are solely to blame.

"Merkel's empire crumbles!" said one newspaper headline.

AfD supporters were overjoyed by the party's success on Sunday

How the parties polled:

SPD (centre-left Social Democrats): 30.6%

AfD (anti-immigration Alternative for Germany): 20.8%

CDU (centre-right Christian Democrats): 19%, its worst ever showing in the state

The leader of her sister party in Bavaria, the CSU, has - not for the first time - issued a public ultimatum.

Horst Seehofer, long a thorn in Mrs Merkel's side, is demanding she produce a clear strategy on tax, domestic security, pensions and immigration within weeks.

He has his eye on next year's general election. So, of course, do the opposition.

Ralf Stegner, the deputy leader of Mrs Merkel's junior coalition partner the SPD, says she is "past her zenith", and casts doubt on whether she should stand for another term. Mrs Merkel has, so far, refused to announce her candidacy.

Tensions between Horst Seehofer and Mrs Merkel appear to have worsened after the election defeat

One senior conservative told me sadly Mrs Merkel now personified the refugee crisis.

She may, he acknowledged, never recover politically. There were doubts within the party, he said, as to whether she should stand for another term.

And it is tempting to wonder, in the words of one newspaper headline, "how much more can Merkel take?"

A fortnight ago, I watched as she swept through the marketplace in Ribnitz-Damgarten - part of her home constituency - campaigning ahead of the recent regional election.

She was greeted warmly - smiles from the woman selling cheese, flowers from a well-wisher as she headed for a makeshift stage, and applause after she joined in with the regional anthem.

Bear in mind her ratings have tumbled, but at 45%, they are still the envy of other European leaders.

Chancellor Merkel (right) still enjoys strong approval ratings despite a fall in her popularity

Two women stopped to talk, baskets in hand.

"We've always liked her," they said.

"She is a fighter, and we hope she will manage this situation too."

But Wolfgang, walking his dog past a stall stacked neatly with rows of shoes, was worried.

"I don't think she can make it," he said, "unless she gets support from someone else - from Europe, maybe from another continent.

"We also need Russia to help us fight the source of the problem, otherwise it is looking bad.

"She can't do it alone."

Earlier this week, a subdued Mrs Merkel acknowledged she needed to regain public trust.

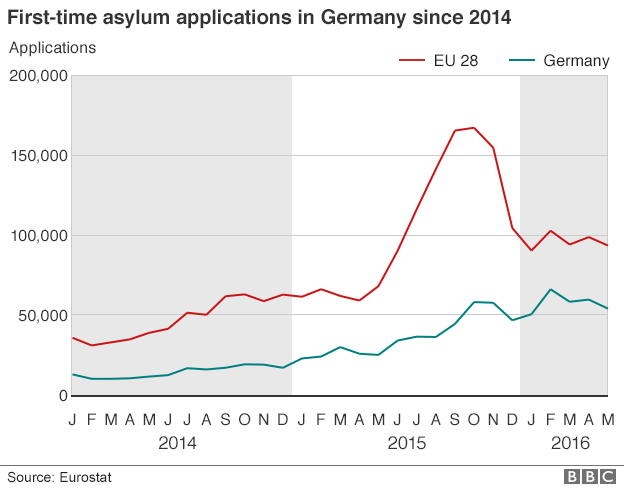

It is no longer enough to point out that the German economy is good, unemployment is low and that refugee numbers have fallen significantly (about 300,000 people have arrived this year compared with well over a million in 2015).

Town and village leaders have told me they can just about manage the current numbers.

Nevertheless, Mrs Merkel is fighting the perception Germany is out of control, and that by - in effect - opening the country's doors last summer, she has put Germans at risk.

Take Gerhard Koch, one of dozens of AfD supporters who gathered recently for a hustings in the town.

"Mrs Merkel," he said, "has betrayed her party."

"We had high hopes in her.

"But she took positions which the CDU used to fight against. She has betrayed the German people.

"If I think about my children and grandchildren - about their future - what she did has incalculable consequences for our fatherland."

Is Germany's AfD racist?

And, in AfD, all of Germany's established parties have a powerful adversary.

The relatively new, chaotically led AfD speaks a strident language, which is proving attractive to those voters concerned about integration and domestic security.

At the hustings Konrad Adam, a former journalist and one of the party's founders, received applause as he declared Islam had no place in Germany.

"Many of these new arrivals have little or no education at all," he said.

"They are culturally behind us.

"They can't or don't want to integrate, and promote their own ideas about how to treat women.

"But Mrs Merkel thinks with a few lessons in German and sex education, we can make up for it quickly."

Mrs Merkel herself acknowledged the refugee crisis would change Germany.

Arguably, the most seismic shift may yet be at political level.

AfD is almost certain to gain seats in the national parliament next year, complicating future coalition building.

And there are those here who believe this is the beginning of the end for Mrs Merkel.

One political pundit has described this time as the "Kanzlerdaemmerung" - the chancellor's twilight.

That may be premature.

There is, after all, no serious contender to replace her.

But Angela Merkel needs to act swiftly.

She has said: "Wir schaffen es [We can do it]," often enough.

Now, she needs to convince her country that she can and - more importantly - explain how.

- Published5 September 2016

- Published11 February 2020

- Published3 September 2016

- Published28 August 2016

- Published7 August 2016

- Published14 March 2016