Apple tax case: Why is Ireland refusing billions?

- Published

Ireland's finance minister, Michael Noonan (right), said he had "no choice" but to appeal the ruling

The European Commission thinks Apple owes the Irish Republic 13bn euros (£11bn). The country's government - and a majority of the population - disagree.

It is a position that seems odd in light of Ireland's recent history of economic trouble.

So why doesn't Ireland want such a huge cash windfall?

It is important to understand that foreign direct investment from large multinationals has been a cornerstone of Ireland's economic strategy since the 1980s.

Companies like Apple, Intel and Pfizer employ thousands of people, particularly in regions outside the capital.

And while Ireland has much to recommend it - a well-educated, English-speaking, European workforce - it also has a very low corporate tax rate of 12.5%.

Apple's Cork office, in the south of the Republic, employs over 5,000 people

That rate of corporate tax was jealously guarded during Ireland's recent bailout, when international lenders mooted raising it - but successive finance ministers have kept it firmly off the negotiating table.

Ireland has, in the past, been accused by its European neighbours of being a tax haven - and has moved to address concerns. In 2014, under international pressure, it closed off the infamous "double Irish" tax loophole.

But this time, the government has repeatedly insisted that tax benefits available to Apple were not exclusive, and the law was "applied fully".

Ireland is simply unwilling to compromise over its reputation as an investment destination.

What is public opinion?

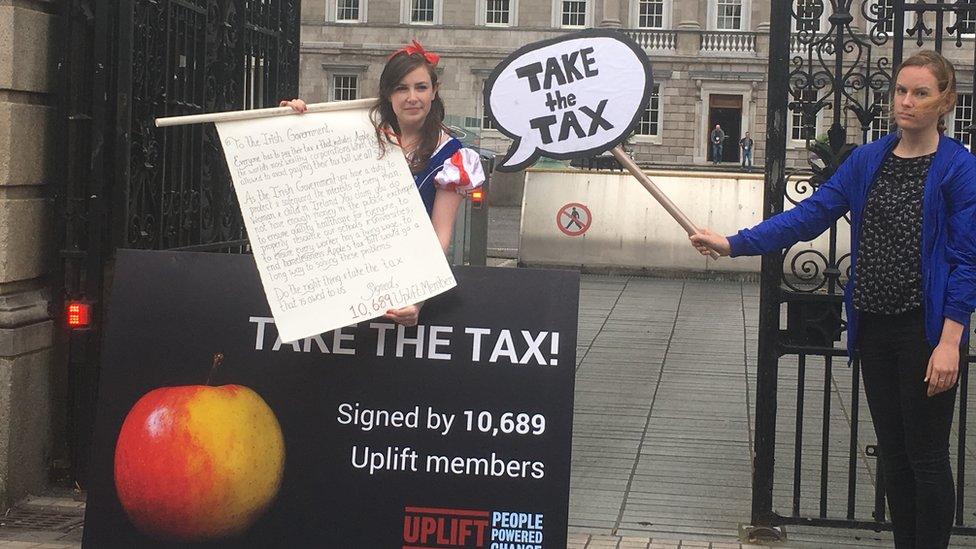

A small number of protesters gathered outside the Irish Parliament on Friday

Refusing a cash windfall that could boost the country's entire national budget is a difficult political ask, even for those who agree with Ireland's low corporate tax rate and incentives to foreign investment.

Yet despite the potential benefits, a poll for the RTE, the national broadcaster, found 62% of respondents said there should be an appeal. Only 24% disagreed (with the remainder not sure).

Many greeted the announcement with some trademark Irish humour

And the situation is even more one-sided and clear-cut among politicians.

Ireland has a minority government. The main party, Fine Gael, has only 50 of the 158 seats, and is supported by a collection of independents.

Its ability to govern is mostly down to the country's other main party, Fianna Fail, which has agreed to support its traditional rival on major policy issues such as the national budget - and it also backs an appeal.

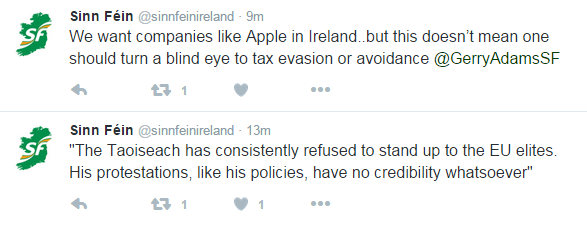

Opposition, therefore, comes from Sinn Fein and smaller parties, which are broadly left-leaning, and believe the 13bn euros (£11bn) could be put to good use.

Sinn Fein is among the groups calling to accept the ruling

Richard Boyd Barrett, of People Before Profit, accused Apple of wilful tax evasion, and "robbing" the people of Ireland.

However, the cabinet has already decided to appeal against the ruling - with the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) telling the Dail that it is a matter for the executive.

The public debate is seen by many as little more than political theatre.

How Apple was taxed in Ireland in 2011

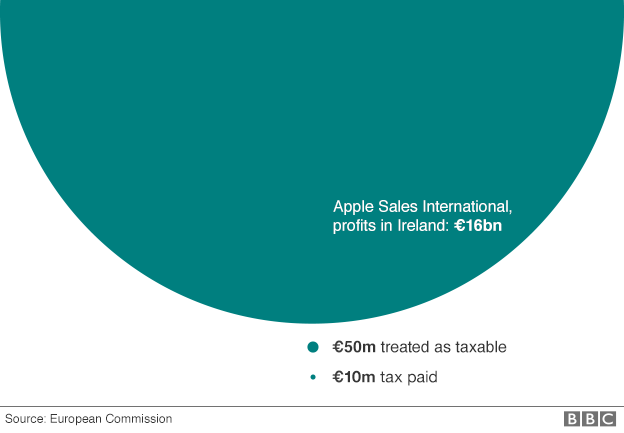

In 2011, as in previous years, every Apple product sold in Europe, Middle East, Africa and India was recorded as a sale by Apple Sales International in Ireland.

Under its tax arrangement, Apple Sales International then allocated the vast majority of its profits to a head office. According to the EU Commission, this head office existed "only on paper" and therefore its profits were not taxed. Only a small percentage of profits were allocated to the Irish branch of Apple Sales International.

As a result, the final 10 million euros tax paid by Apple was equivalent to a rate of 0.05% - this fell to 0.005% by 2014 as profits rose - far less than the 12.5% Ireland charges other companies.

Another company, Apple Operations Europe, also based in Ireland, operated in a similar way.

Who would get a slice of the money?

While much has been made of the benefits an extra 13bn euros would bring to Ireland - it is the cost of the entire national health budget, and two-thirds of the social welfare bill - it is far from certain Ireland would gain that much.

The crux of the whole matter is that sales of any Apple product or service, anywhere in Europe, were officially considered to take place in Ireland - at a very low rate of tax.

But the European Commission said that other countries could claim part of the tax if they believe that sales (and other activities) "could have been recorded in their jurisdictions."

Ms Vestager said the Irish tax system "allowed profits to be attributed to a head office that only existed on paper."

On top of that, the commission said, Ireland's tax take could be reduced if the US forces Apple to pay more back to the parent company.

This leaves Ireland at the centre of an uncertain tax situation on both sides of the Atlantic.

In the meantime, the 13bn euros total is likely to be placed into an escrow account for safekeeping while Apple and Ireland appeal against the ruling - a process which could take years.

What about Apple?

Tim Cook, CEO, Apple: "It's maddening and disappointing"

The technology titan is rare in that it can actually afford to pay 13bn euros - its cash reserves are estimated at over $200bn.

But it is furious about the ruling, with CEO Tim Cook branding it as "maddening".

"It's clear that this comes from a political place, it has no basis in fact or in law, and unfortunately it's one of those things we have to work through," he told RTE. But he said the company remained committed to Ireland.

The confusion comes during a difficult year for Apple. It has seen falling sales, a public legal battle with the FBI over digital privacy, and is releasing the latest version of its iPhone in the wake of this tax row.

It is believed Apple will repatriate several billion dollars in profits to the US next year. Under US tax codes, tax is only payable (at 35%) when profits are brought back to the US - which is why many companies leave them overseas, hoping for a lower rate to appear.

- Published7 September 2016

- Published2 September 2016

- Published7 September 2016

- Published1 September 2016

- Published30 August 2016