Natalia's struggle to be heard in Russian election

- Published

'I'm not under their control... that's why they're so nervous.'

There is a large, rust-coloured blank space where Natalia Gryaznevich's face once looked down on a suburb of St Petersburg. The election billboard of the young opposition candidate is one of two that were vandalised; on the other, her name has been painted over in black.

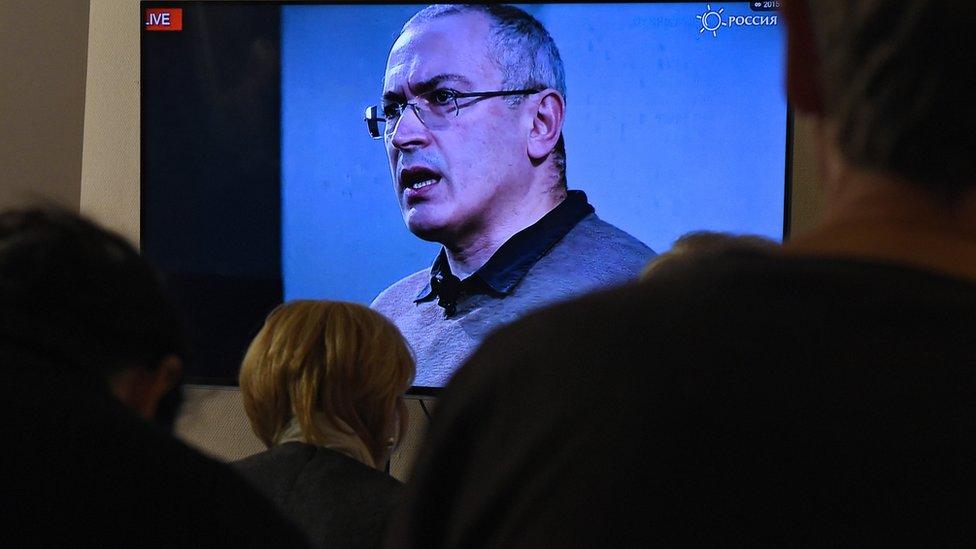

The 27-year-old is among a group of 18 candidates running for a seat in Russia's parliament this weekend, openly supported by Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a sworn enemy of President Vladimir Putin.

The former oligarch, who is now in exile, spent a decade in prison here on fraud charges which he says were politically motivated.

Natalia, officially a candidate of opposition party Parnas, was initially afraid of accepting the ex-oligarch's backing. "I didn't know what to expect," she said,

Natalia's name has been erased from one of her campaign billboards, but the slogan "real opposition" remains

But, to the surprise of many, all but one of the candidates supported by Mr Khodorkovsky's Open Russia movement were cleared to run for parliament.

That's a big change from the 2011 election when Parnas itself was barred from the race.

But Natalia says it hasn't been a fair fight.

Natalia faces an uphill battle to get her voice heard

Among a chaos of campaign leaflets and stained mugs in her basement headquarters are dozens of letters from the local authorities.

Repeated requests to erect information stands and hold rallies in her constituency have been refused. One rejection claims her campaign could create social "tension" with other candidates.

"They are afraid of any opposition, even if it's not so big or powerful," Natalia argues, on her way to court to lodge an official complaint against her main rival from the governing party, United Russia.

She has spotted posters with his photograph offering free concert tickets and wants the candidate removed from the race for buying votes. The court ultimately rejects her complaint.

"They are afraid when there is something they can't control. I am something that is not under their control in this election. That's why they are so nervous," Natalia believes.

Perhaps that is why state television has gone on the attack.

Targeting Khodorkovsky

While news programming has been filled with images of President Putin alongside Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev (the official head of United Russia), last week state-controlled NTV showed the latest in a series of films smearing Russia's opposition.

Its expose, Eighteen Friends of Khodorkovsky, alleged that the former oil tycoon was funding candidates directly from abroad in violation of Russian rules.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a sworn enemy of President Putin, spent several years in jail before being allowed to leave Russia

The film claimed that his aim was to declare the vote invalid and spark mass protests like those that followed evidence of fraud at the last elections.

"There is nothing they are afraid of more," argues Vladimir Kara Murza, co-ordinator of Mr Khodorkovsky's Open Russia movement. He was detained himself last week, at a campaign rally for another opposition candidate which police said had not been authorised.

"I think this [fear of protest] is the biggest, if not the only reason they are going to such lengths to create an appearance of free and fair elections. But I think it's important not to be fooled."

Open Russia says it provides expert advice and support for candidates like Natalia Gryaznevich, including lawyers and PR, not cash. But the movement does admit it has an agenda.

"We want to show that there are people who have a different vision and want to see Russia as a modern, European democracy," Vladimir Kara Murza explains.

But the odds look stacked against them.

While Natalia was not allowed to erect a stand, candidates from the ruling United Russia party were

Outside a St Petersburg metro station, a man in a bear suit hands out political newspapers for the local United Russia candidate. The front page sports a big photograph of President Putin.

Next to the bear is an advertising stand for the governing party, right on the spot where Natalia was refused permission to campaign.

Looking to the long term

That evening, when Natalia arrives in the yard of an apartment block for a pre-advertised meeting with voters, no-one turns out to hear her.

"I know that 100 people got the invite," the young politician shrugs, putting a brave face on it. "Maybe they don't want to come outside and listen. But they know I am ready to meet them and that's the most important thing."

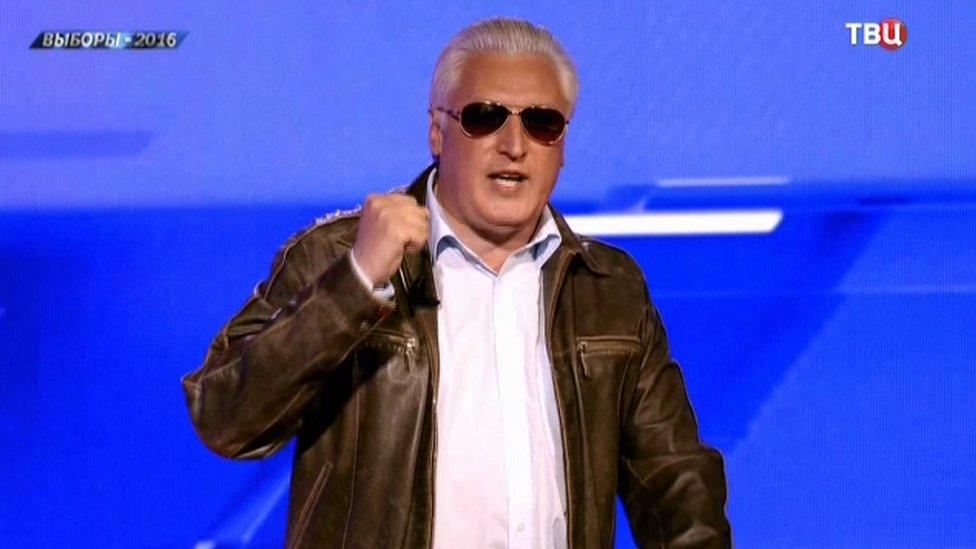

Vladimir Kara Murza, co-ordinator of Mr Khodorkovsky's Open Russia movement, says allowing opposition candidates is just a ploy

Open Russia argues that it is playing the long game.

"We want to use this as a training ground for a new generation of political activists, to get them experience," says Vladimir Kara Murza, recalling the story of virtuoso Soviet pianist Rudolf Kehrer. Exiled to Kazakhstan during World War Two, he was forced to practise for years by playing on a plank of wood.

"We know that all regimes end. And when the time comes, we have to be ready," Mr Kara Murza argues.

Russia's struggling opposition

Fourteen parties are standing for the Duma, but only two are regularly critical of the Kremlin

Russia's lower house of parliament, the State Duma, has 450 members and is being elected for a five-year term.

Four parties had MPs in the outgoing parliament and it was almost totally dominated by supporters of President Vladimir Putin

Outspoken anti-Putin MPs were stripped of their mandates

This time half the Duma will be chosen by constituencies and half from party lists

The same four parties are expected to win all but a handful of seats

Fourteen parties are running but only two are consistently critical of the Kremlin.

The opposition is weak and disunited and media coverage, especially on state TV, strongly favours the ruling party United Russia.

The previous election in 2011 was marred by allegations of fraud, which led to mass protests in Moscow

- Published13 September 2016

- Published10 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016

- Published5 September 2016

- Published25 August 2016

- Published25 March 2024