Russian bullet train whirrs past bleak lives

- Published

German-built Sapsan high-speed trains can reach 250km/h and carry up to 600 passengers

It's early morning in Moscow as the Swallow commuter train pulls out of Leningrad Station.

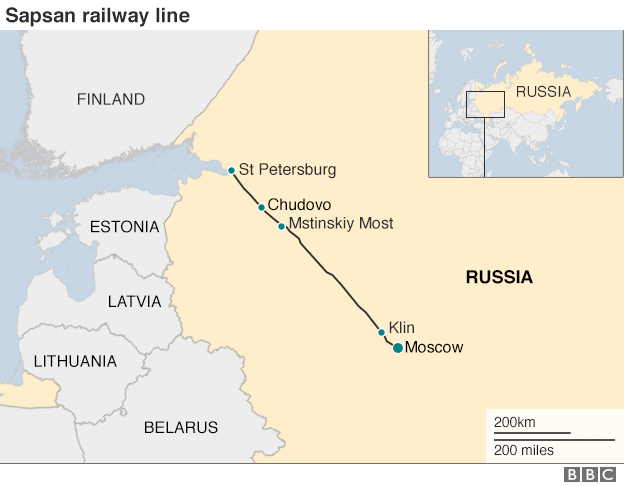

I'm on the first leg of a 650km (400-mile) journey to Russia's second city, St Petersburg - a route that has seen a revolution in rail travel.

For those who can afford it, the new Sapsan high-speed service has cut journey times from eight hours to just four, offering luxury, leg room and onboard Wifi.

But I'm foregoing this high-tech, 21st-Century experience and will be travelling on ordinary suburban trains.

I want to find out if progress on the railways has been matched by improvements in the lives of ordinary Russians living near the tracks.

The Swallow is full of business travellers, and I'm sitting next to Pavel, a middle-aged company manager.

He is reading a fantasy novel about time-travelling Stalinist secret agents.

"Stalin was a man who made our country great," says Pavel, as we rattle through Moscow's bleak suburbs.

"Everything was ruined in the 1990s, and the people in charge aren't making any attempt to rebuild it."

In 2009 Vladimir Putin - prime minister at the time - inaugurated the Sapsan high-speed service

Spirit of Tchaikovsky

Our first stop is Klin, a nondescript town 90km outside Moscow.

Its main claim to fame is composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, who spent his summers here.

The town hopes the legacy of the great 19th-Century composer will help revive its 21st-Century fortunes.

Two years ago a well-connected businessman, Igor Chaika, launched an ambitious project to turn Klin into a Russian Salzburg, like Mozart's much-visited birthplace in Austria.

There were plans to revamp the town centre, build a metro, and start an annual Tchaikovsky festival.

Two years on, Igor Chaika has pulled out, but his name and the project featured in a widely-publicised opposition video last year, accusing him and his father - Russia's chief prosecutor Yuri Chaika - of corruption. Both deny the allegations.

Klin still has no metro, but there is a music festival, and Alyona Sokolskaya, the town's smartly-dressed mayor, is happy to talk about it.

But when I ask about Igor Chaika, the conversation abruptly ends.

"Are you here to interview me or to talk about Chaika?" she asks icily, and I am escorted from the building by security.

Tchaikovsky chose Klin because it was on the railway - it is where he wrote his last symphony

Later, back on the train, we wait in a siding in Tver region, waiting for the Sapsan to race past.

Passengers say delays of up to an hour are common now.

I meet Natalya, a well-spoken former teacher who makes a living selling small items to passengers on the trains.

She's been doing this 10 hours a day, six days a week, for 20 years.

In a good month she earns the equivalent of $300 (£245) - much more than her teaching salary. But it's a hard life.

"Sometimes I don't want to come to work so much I feel sick, "she says. "But that's life. Russians are used to being under the cosh."

The Kremlin's red stars came from a glass factory near the railway line

A sign warns passengers to beware of high-speed trains hurtling through

The next stop is Leontevo, once famous for its glass factory, which made the ruby stars on the Kremlin towers.

In 2010 Nina's son Mikhail was knocked off his feet by a Sapsan roaring through the station.

Furious, he hurled a lump of ice at the train and was prosecuted for criminal damage.

It was Mikhail's third conviction - not unusual for a generation who came of age amid the chaos of the 1990s.

With no work or prospects, life offered Mikhail little except drink and crime.

Two years after his Sapsan conviction he was dead.

"It was hard living with him," says Nina. "But it's even harder without him."

Nina bears no bitterness towards the Sapsan, but she's troubled by the inequalities of life.

"Yes, we need progress," she says. "But is there any guarantee that people who live along the tracks will be safe and comfortable?"

'Great leader' Stalin

Nina's old friend Slava is scathing about how the ruling United Russia party is running the country,

"Haven't they stolen enough?" he asks.

"They've bought land, built houses, salted money away, and sent their children abroad. Isn't it time to do some good?"

But Slava deeply respects President Vladimir Putin, and says he'd like a return to the Soviet discipline of Joseph Stalin's era.

"If you weigh up the prison camps on one side, and what Stalin achieved on the other, then to me he was a great leader."

Oleg was abandoned by his parents at the age of six and after long spells in prison he now lives on the trains

Early the next morning we're rolling through Novgorod region.

A young man with a child's face is lying across the seat opposite.

He doesn't have a ticket but the conductor leaves him alone.

Oleg is 29 and homeless. He grew up in a children's home, spent seven years in prison and now travels the trains begging money for food and cheap wine.

"I drink to keep warm," he says. "Not to get drunk."

Much-quoted poem

At Mstinskiy Most station a bell rings non-stop, warning passengers a fast train is approaching.

"That's how it should be," says Olga, at the station shop. "A Sapsan might come through at any moment."

I'm staying with Maria, a cheerful widow in her mid-sixties who runs a guest house.

Maria is a karaoke fan and clearly enjoys life.

"Whatever people might say, we're okay here," she says.

Maria rents out rooms at three dollars a night with breakfast and dinner

The last stop before St Petersburg is Chudovo, once home to the poet Nikolai Nekrasov.

He wrote one of his most-quoted poems here, titled: Who Can Be Happy In Russia?

I'm still thinking about Nekrasov as we finally reach St Petersburg.

It's three days since I started out, and almost 150 years since Nekrasov wrote the poem.

Life along the tracks is clearly moving much slower than the Sapsan train, and Nekrasov's question seems as relevant as ever.

- Published25 October 2016

- Published11 October 2016

- Published4 September 2016

- Published17 March 2024