Why Spanish school kids are refusing to do their homework

- Published

Manuel took advantage of a wet weekend in Madrid to indulge in some quiet reading

Brothers Martin and Manuel enjoyed the kind of weekend they like best, lounging around at home in Madrid.

Their mother, Gracia Escalante, is one of millions of Spanish parents asked to observe a homework strike each weekend in November.

"Manuel (year nine) loves to read and Martin (year six) really needs time to lie on his bed and imagine things, not just playing with the tablet or watching TV. And certainly not doing schoolwork," she says.

The protest was called by the Spanish Alliance of Parents' Associations (CEAPA), which argues that homework is harming children's education and families' quality of life.

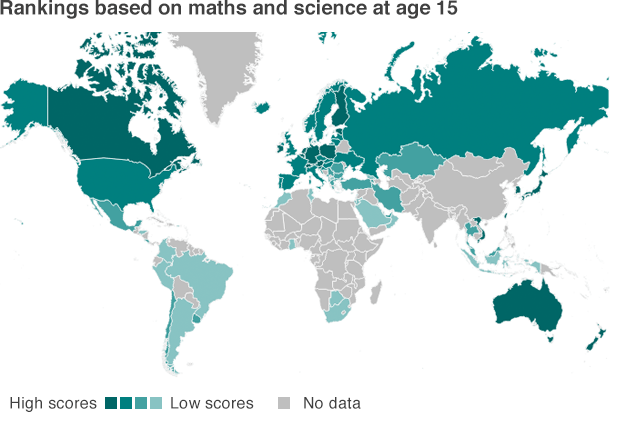

Spain ranks highly among industrialised countries in terms of homework set, but can boast only mediocre positions when it comes to academic achievement.

According to a 2016 study by the World Health Organisation, 30% of Spanish 11-year-olds feel stressed by the amount of homework they have to do, rising to 65% by the age of 15.

Those who support the strike say the amount of homework children get - often two hours or more a day - is the direct result of an old-fashioned system of rote learning, constant examinations and a lack of school resources or modernised thinking in Spain's education system.

"Some teachers try to be different, but when you have 25 students in the classroom at primary level and constant pressure from evaluations, the only way the Spanish system stays afloat is by children doing homework," says Ms Escalante.

"Kids are stuck at home doing homework instead of learning to relate with grandparents, cousins, all the different kids in their street, learning to cook, how to fix a broken pipe."

Eva Bailen started a petition and has written a book called How To Survive Your Child's Homework

Eva Bailen, who started a petition against homework, believes primary school children should not have more than half an hour's homework a day and older children one hour.

Elsewhere in Europe:

Among teachers, who have also been asked by CEAPA not to set homework on weekends this month, some sympathise with the aims of the strike.

"I don't set homework at all," explains Alvaro Caso, a primary school teacher in Aravaca, near Madrid. "Children spend enough time at school and have enough work to do during the day. If a teacher is doing their job right, there is no need for any more - at least in primary education."

Violeta Ruiz believes overloading children with homework is counterproductive but disagrees with the strike

Alvaro Caso argues that Spain's rowdy politics has seen the education system reformed six times in the past 35 years, but without any analysis of the big picture in terms of today's society.

"It's all still very dry and academic. Never mind the last century, there is still a lot of the 19th century about our schools. If a child falls behind, there is not much of a learning culture to hold on to, just studying and repetition."

Who's against the strike?

"It's awful to hear my son ask why he has to work in the evening when I have finished," says Violeta Ruiz, a university lecturer and mother of two boys in primary education.

But she does not support the strike. "I am completely against it because it's taking a swipe at all teachers without discriminating, and without prior consultation."

Unions have also criticised the confrontational aspect of a strike, which they argue questions teachers' authority.

Juanma Fabre, a teacher of philosophy to Baccalaureate students in Madrid, accepts there is too much homework, but says teachers are not to blame.

"As a father myself, I have seen how bad it can be. Teachers and students are oversaturated with work."

Mr Fabre points out that state schools have no system of coordination between teachers so students might get work from all eight or nine subjects at the same time, with Spanish language, maths and foreign languages like English providing the biggest workload.

"The national curriculum is impossible to cover. Each education reform talks about modernising the methodology and moving away from memorising things to working on skills, and then adds more material to the syllabus."

For Ms Ruiz, great loads of homework are actually counterproductive for the learning mind.

"Having three hours of homework to do is a direct attack on the development of a reading habit. No child sits down to read from 17:00 to 17:30; they have to be in their room, get bored and eventually take a book down from the shelf."

How much homework do children get?

Spanish 15-year-olds were found to get an average of 6.5 hours per week

UK 15-year-olds got 4.9 hours per week, close to the international average

Finland's teenagers are set less than three hours a week, and yet are consistently in the top 10 international Pisa rankings

Shanghai, China, tops the Pisa 2012 rankings for 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science, but also sets the most homework: 13.8 hours

Do you think your children get too much homework? Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external

- Published28 September 2016

- Published27 October 2016