François Fillon: French candidate devoured by 'fake jobs' affair

- Published

François Fillon's hopes were dealt a dramatic blow by a series of revelations

For a brief period - between November 2016 and January 2017 - François Fillon was the great hope of a resurrected French centre-right.

At 62, the former prime minister - long written off as an unexciting political dogsbody - had trounced the opposition in the Republicans' party primaries and was seen as a shoo-in for next head of state.

After the flamboyant egomania of ex-President Nicolas Sarkozy, François Fillon's grave demeanour seemed appropriate for the country's troubled times. His programme of tough budget cuts and mass job losses in the state sector was painful but honest.

Here was someone at last, said supporters, who grasped the truth of the economic crisis and would act boldly to restore France's fortunes.

And then came Penelopegate.

Penelope Fillon told a newspaper in 2016 she had never been involved in her husband's political life

The affair over payments to François Fillon's British wife, for work she may or may not have done as his parliamentary assistant, burst on to the news in January 2017 and was followed by a drip-feed of ever more salacious revelations about the candidate's lifestyle and wealthy connections.

In March he was placed under judicial investigation - a first step towards a possible trial for corruption.

Only a few months earlier, in a jibe aimed at Mr Sarkozy, he had asked ironically who could imagine the great Gen Charles de Gaulle running for office while under such doubts over his personal integrity.

Now here he was blithely ignoring his own moral precept. As the presidential campaign got under way, François Fillon was already damaged goods. His poll ratings tumbled and the party despaired.

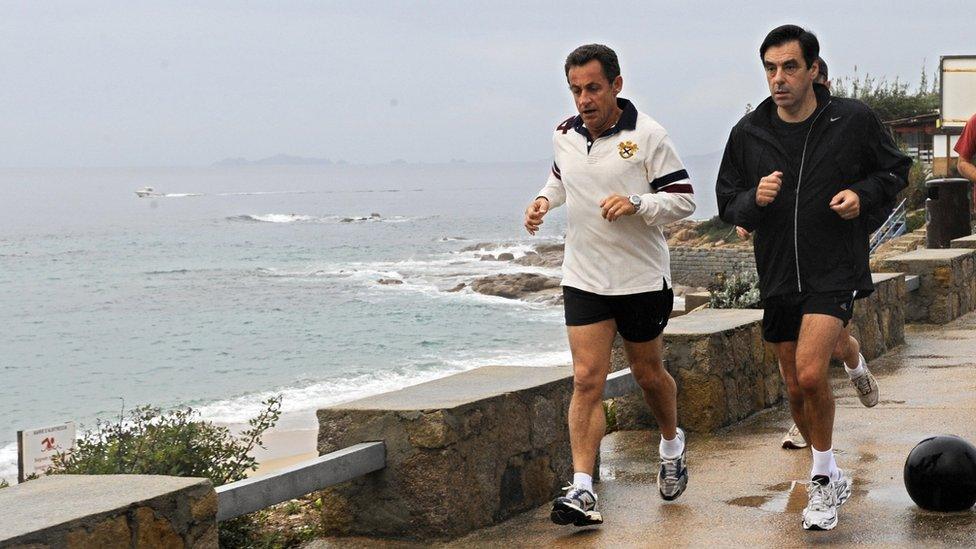

Then-President Nicolas Sarkozy (L) and Francois Fillon jogging: Mr Fillon would later thwart Mr Sarkozy's comeback hopes

The odd thing is that up to that point there had not been a hint that his weak point might be money. On the contrary, the image he constructed over nearly 40 years in politics had been sober, undemonstrative and provincial.

The Gaullist

It was in 1981, at the age of 27, that François Fillon was first elected as a member of parliament, becoming the National Assembly's youngest member.

His party was the Gaullist RPR of Jacques Chirac.

His history professor mother and lawyer father were also Gaullists, and he was brought up in comfortable circumstances near the western city of Le Mans.

He studied journalism and then law. In 1974 he met his future wife Penelope Clarke.

They have five children, the last born in 2001. They live near Le Mans, in the Sarthe department which remains the Fillon powerbase.

This medieval chateau near Le Mans is now Mr Fillon's family home

François Fillon's first ministerial post, in higher education, came in 1993 under Prime Minister Edouard Balladur.

He went on to hold five other cabinet posts, before serving as prime minister for five years until 2012 under Nicolas Sarkozy.

For nearly all that time, he was identified with the movement known as "social Gaullism" - roughly equivalent to one-nation Conservatism in the UK.

His friend and mentor was the late Philippe Seguin, who believed in strong state intervention in the economy and society. Mr Fillon also shared Seguin's Euroscepticism, and in 1992 both men voted against the Maastricht Treaty that ushered in the euro.

Later, as social affairs minister under President Jacques Chirac, Mr Fillon had the image of an honest dealer prepared to put in the hours during long negotiations with trade unions.

All of which sits rather oddly with the policies of François Fillon the presidential candidate, which are avowedly those of a radical economic liberal.

Free marketeer

In speech after speech, he has spoken in cataclysmic terms of France's "broken" social model, and of the need for drastic cuts in state spending.

"Sometimes you need to tear the whole thing down," he says.

For his enemies, this virage libéral (liberal economic U-turn) is an easy point of attack. Another is his religion.

François Fillon is a practising Catholic.

Mr Fillon's performance in a debate featuring the main presidential candidates appeared lacklustre and subdued

He is personally opposed to abortion but says he would never seek to repeal the law. Nor would he ban adoption by gay male couples, although he wants the law changed so that a child can trace its birth mother.

For the left, these are signs of worrying ambiguity on matters that are central to a progressive society. Some accuse him of pulling the Republicans on to territory normally occupied by Marine Le Pen's National Front.

In the end, though, these arguments scarcely had to be deployed against him because his whole campaign has been devoured by l'affaire (the scandal). The self-destruction required little help from his opponents.

Lessons from the wealthy

The picture of the man that emerged was not one many would have recognised.

The public learned that for years he had employed Penelope as his parliamentary assistant, earning her large sums in public money, even though she rarely, if ever, went to the National Assembly. He gave similar short-term jobs to his children.

François Fillon had friendships with some very wealthy people. One of these, billionaire Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière, paid Penelope for what appears to have been little more than a sinecure at a literary magazine which he owned.

Mr Fillon has long had a passion for motor racing

It also emerged that he had run an international consultancy offering help arranging meetings with influential people. He had personally accepted gifts of suits and watches worth tens of thousands of euros.

In some countries, perhaps, this would not have mattered so much but France does not warm to the very wealthy, especially when they give out lessons.

To the public it seemed that he was tut-tutting about public sector indulgence while indulging the lavish lifestyle of a country gentleman, replete with his hobby for motor-racing.

Making matters worse was his reaction, blaming a conspiracy of left-wing politicians and magistrates bent on bringing him down. He even personally named President François Hollande who, he said, ran a "dark cabinet" keeping tabs on political enemies.

François Fillon's core voters have remained loyal but an election that should have been there for the taking looks like it has been thrown away.

If he loses, he will have few friends in politics. The dark horse who became the great hope may soon become the black sheep.

- Published24 April 2017

- Published14 March 2017

- Published11 May 2021

- Published29 March 2017

- Published22 November 2016