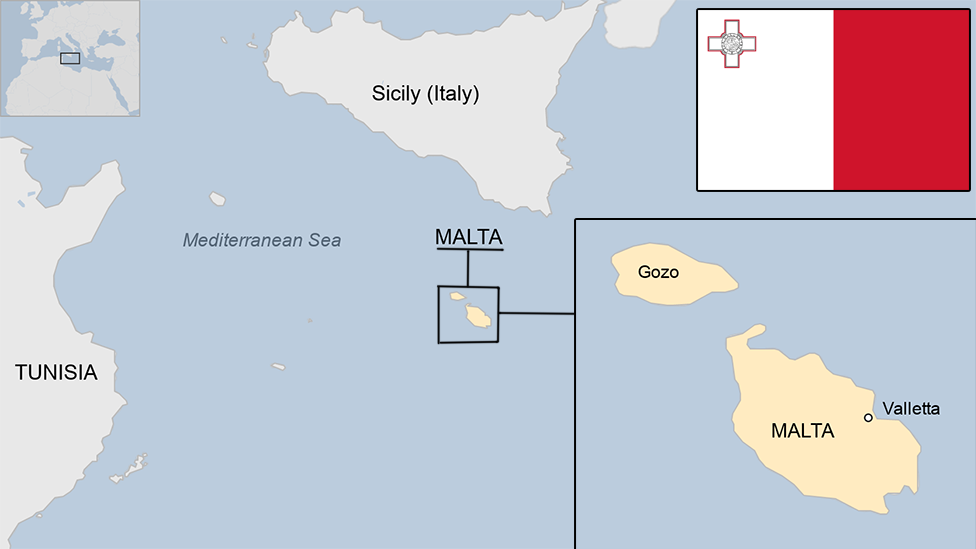

Malta's paradox: A beacon of gay rights that bans abortion

- Published

Staunchly Catholic Malta outlawed divorce until 2011 but in the last five years has seen sweeping social changes

The last five years have seen sweeping changes in laws governing social and sexual rights in Malta.

In 2011, it was one of the last two countries in the world where divorce was illegal.

On Tuesday, it became the first European country to ban "gay conversion therapy", eliciting cheers from LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) campaigners as well as psychologists.

In recent years, the staunchly Catholic country has:

Legalised divorce

Granted rights equivalent to marriage to homosexual couples, including the possibility to adopt children, and become one of only five countries to accord LGBT people equal rights at constitutional level

Passed the Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act (GIGESC Bill), banning invasive "normalising" surgery on intersex people, outlawing their sterilisation and allowing people to self-determine their own gender in law without medical examination

Been named the best European country for LGBT rights by advocacy group ILGA-Europe

And yet Malta is now the only EU country where abortion is banned outright.

Why has so much changed in five years?

In 2011, social pressure for change had been building and the "lid was lifted" by a referendum that backed legalising divorce, says Herman Grech of the Times of Malta newspaper.

"The referendum changed everything - and the results were pretty surprising for a country where the Church has been dominant," he told the BBC, and where the centre-right Nationalist party was in power.

"Suddenly people and the younger generation voted in favour as they realised it was one of only two countries [including the Philippines] that outlawed divorce."

"That tilted everything - people started saying we can start tackling other social issues."

That process accelerated once the Labour Party came to power in 2013, says Herman Grech.

He believes Malta joining the EU in 2004 changed the outlook of its young people. Travelling and studying in Europe "opened their minds", he says.

Malta has one of the highest per capita usages of social media in Europe.

And yet Malta's abortion laws remain among the strictest in the world, don't they?

In Maltese law abortion is banned even in cases where the mother's life is threatened (though, in practice, there is an exception if the foetus is harmed in the course of essential treatment for the mother, the so-called "double effect" law).

For women's rights campaigner Francesca Fenech Conti, women's reproductive issues represent one of the last bastions of conservatism in a patriarchal society dominated by the Church.

"There are a lot of women Church followers who are still devout, and think they should be mothers first," she told the BBC. "Condom machines were only provided in universities last year."

For Mr Grech, abortion remains a "delicate subject - even for those in favour of gay marriage. At the back of our minds we've always been told it is murder".

What is the Church's view of all this?

The Catholic Church in Malta is led by Archbishop Charles Scicluna, described by one commentator as "pragmatic rather than fire and brimstone - a bit like Pope Francis".

The Catholic Church, headed in Malta by Archbishop Charles Scicluna, is still influential in matters of social policy

Asked by the BBC for his view of social changes in Malta, he said in a statement that although the Church "remains committed to promoting the values of the family and of marriage between a man and a woman", it also "recognises that Maltese society is changing at a sustained momentum... [and] that there are positive aspects to the increased respect for the dignity of every person, irrespective of their gender or their sexual orientation."

Will the abortion ban be swept away too?

Not if the Church has its way.

It has campaigned on issues that it feels could erode the ban - intervening in a recent debate over access to the morning-after contraceptive pill, arguing that in certain cases it could be used as an abortifacient (abortion-inducing) and thus opposing its legalisation.

"We remain committed to defend the most vulnerable and the voiceless in society, such as the unborn child," said Archbishop Scicluna. "The Church believes that unborn children too deserve to be treated with dignity, a belief that is also shared by the vast majority of Maltese society."

But for Ms Conti, Malta will be unable to hold back the tide of change - even in this hitherto taboo area.

"There will be changes soon - that we are even having this conversation is evidence. A year and a half ago I couldn't discuss these issues with my own sister and cousin - now we talk about it all the time.

"I'm in touch with campaigners in Ireland and Poland [where campaigners are challenging abortion laws]. It will happen."

Mr Grech says it depends on whether campaigners can gain popular backing.

As before, he says, "if people start speaking up, the parties will follow".

- Published6 October 2016

- Published3 October 2016

- Published24 September 2016

- Published18 October 2016

- Published19 June 2023