Grandfather of populism Poujade who shook France and the world

- Published

Pierre Poujade's movement fizzled out but the ideas of Poujadism live on

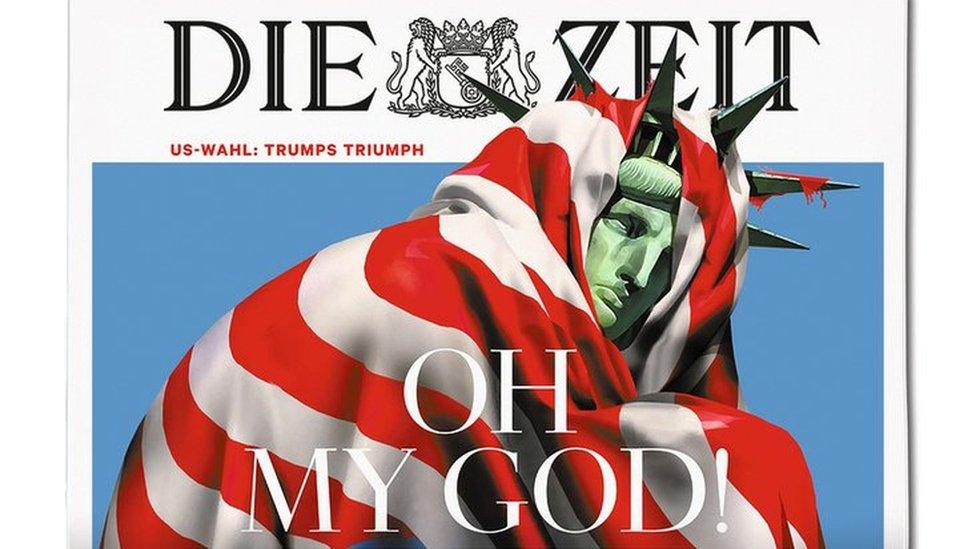

We will remember 2016 as a year of turbulence illuminated by flashes of populist anger - the year of the coming of Donald Trump and the UK's decision to leave the European Union.

It was felt in Italy too, where voters used a constitutional referendum to unseat a prime minister - and it may yet be felt in France where Marine Le Pen, standard bearer of the far-right National Front, seems certain at least to make it to the second round of the presidential elections next year.

The common thread from Peoria to Pinner to Perugia was a surge of angry resentment at establishment politicians - a populist revolt against being told what it is acceptable to think about issues like globalisation, migration and Europe.

Populism in 2016: Read more here

The mood of the moment in 2016 would have gladdened the heart of Pierre Poujade, the French political activist who is a sort of spiritual grandfather to our age of exasperation.

In the period following World War Two, Poujade ran a stationery shop in the little town of Saint-Cere in the Lot Valley, deep in the heart of south-west France, where fruit is grown, wine is made and foie gras is produced.

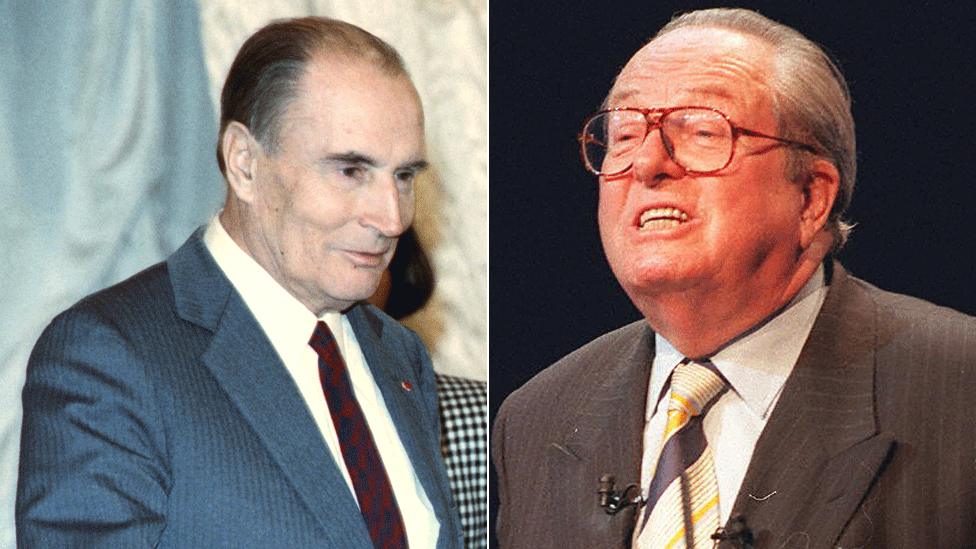

Although far-right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen backed him, Poujade himself preferred Socialist Francois Mitterrand

The local people in Saint-Cere are close and clannish - the authorities in the nearby cities of Bordeaux and Toulouse are regarded with a degree of suspicion, and Paris is practically seen as a foreign capital.

Steve Bellinger, a British expatriate who runs a local B&B with his wife, summed up the local people for us.

"They tend to be very conservative," he said. "They don't like change and they can be very suspicious of people from other areas. They don't tend to move around very much and they're also wary of Parisians and of what goes on in Paris."

'Politics of the outsider'

The spark that ignited the righteous rage of Pierre Poujade was a series of visits to Saint-Cere by tax inspectors, whom local shopkeepers saw as meddlesome bureaucrats choking the life out of small businesses with burdensome demands.

Poujade's protests captured the mood of a country that lurched from one crisis to another. France was painfully losing an empire, at war first in Indo-China and then Algeria.

He was an extraordinary orator. At the peak of his powers he gathered a crowd of well over 100,000 Parisians to a rally at the Porte de Versailles, quite an achievement for a country shopkeeper with no established political party behind him.

Prof Jim Shields of Aston University is an expert on that extraordinary period in French history and is in no doubt that Poujade created a kind of "politics of the outsider" which has a direct link to the campaigns for Brexit and a Trump presidency.

'Weak against strong'

He listed for me the characteristics that all populist insurgent campaigns can trace back to Pierre Poujade.

"Weak against strong," he told me, "Ordinary people against remote elites and simple against intellectual."

Poujade's daughter insists he was not wedded to a right-wing ideology

In the hands of a certain type of politician, Prof Shields argues those attitudes can be intoxicating.

"When Donald Trump rallies forgotten Americans," he says, "when Nigel Farage speaks for the left-behind, when Marine Le Pen appeals to the forgotten and invisible majority, they are all invoking Poujade's defence of the 'little man'."

Poujade is sometimes seen as a figure who emerged from the extreme right, but that misunderstands his appeal and misrepresents his life.

His daughter, Marie-Paul Pons, told me that her father had once told his followers to vote for Socialist presidential candidate Francois Mitterrand because he felt that Mitterrand was prepared to listen to the voices of the forgotten voters of deep, rural France.

For a period in the 1950s Jean-Marie Le Pen - who went on to found the far-right National Front in France - was a member of Poujade's movement, but the two men fell out. Even then Le Pen was an extremist and he was more interested than his leader in professionalising the party and seeking power.

When I asked Madame Pons if she thought her father would have voted for Marine Le Pen in next year's presidential election she was adamant that he wouldn't.

And when I asked why her answer was simple.

"He didn't like extremes," she told me.

Elite of 'isms'

Pierre Poujade's movement eventually fizzled out. It had always been a vehicle for expressing popular discontent than a serious political party with a genuine programme for government.

It had a touch of theatricality about it too - a blood-curdling oath of loyalty - and there was a whiff of anti-Semitism in its loathing of France's Jewish Prime Minister, Pierre Mendes France.

Poujade died in 2003, but he lives on in the anti-establishment spirit of the turbulent year of 2016

Mendes France, who governed with Communist support, enraged the traditional right in France with his enthusiastic support for de-colonisation. And it didn't help that he was known to drink milk at official dinners rather than the great wines of the country he led.

But Poujade lives on in the spirit of the turbulent year of 2016 when the anti-establishment mood he once helped to articulate was felt around the world.

And, interestingly, he lives on too in the dictionary, where you will see "Poujadism" listed.

That puts him in rarefied company - not many politicians have an 'ism' named after them: De Gaulle and Thatcher in relatively recent times, Stalin and Lenin from a more distant past.

Poujade never won power - and probably never wanted it - but his place in history and in the dictionary is assured. The way in which his spirit reverberated in the events of 2016 is testament to the power of the populist spirit he represented.

- Published11 November 2016

- Published9 November 2016

- Published13 November 2016

- Published26 May 2016

- Published10 November 2016