Will Spain's coal belt survive through online barter?

- Published

The decline of coal has led to a revival of rural traditions in Asturias

The sons and daughters of miners in the deserted coalfields of northern Spain face two choices: leave to find work, or innovate to be able to stay.

Now, they have developed an online barter economy, which they say is helping them return to their rural roots. But can it really work?

Javi Fernandez's small house is surrounded by edible plants. Among traditional winter crops grown in this area, like verza, a kind of cabbage, there's also mustard, Jerusalem artichokes, and shiitake mushrooms.

It's a small patch of bounty amid miles of empty, rolling hills.

Rather than study engineering to work in the coal mines like both his father and grandfather, Mr Fernandez studied agriculture in Cuba.

"I couldn't afford to go to a paying university so I studied for free at the ISCA University, in San Jose de las Lajas," he beams, digging through the 400 sq m (4,300 sq ft) of artichokes he has planted.

Ghost towns

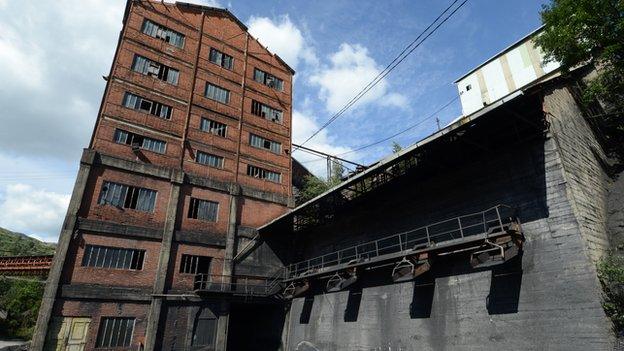

Asturias became a centre for coal production in Spain in the late 19th Century, but waves of closures have left whole towns deserted and hundreds of thousands of miners unemployed.

And the EU is ending all subsidies for the coalfields by 2018, sounding the death knell for the industry in the region.

Cultivating mushrooms enables Javi Fernandez to get things he needs through barter

Javi brings a range of produce to market, thanks to skills he learnt in Cuba

Javi Fernandez uses a traditional Asturian technique to grow his mushrooms: harvesting branches from the forest, drilling small holes and impregnating them with spores, before covering the holes in beeswax and leaving them in the dark for a year. Then he makes shiitake pate, dries and cures the mushrooms, and powders them so they can be taken in pill form.

For all his work, he earned no money at all until recently. Instead, he put his produce into an online barter economy, trading it for other things he needs.

"Up in the mountains there's a serious liquidity problem," he says. "People find it easier to barter because money simply isn't available."

Twice a month, he takes his produce to a local village market, with a sale already agreed online.

Other young people, also trying to survive in the mountains, come with a wide range of offers, from building, teaching and manual labour to giving legal advice and translation.

Spain is far from the only country where barter is gaining traction at the margins of the economy.

Barter is probably the oldest form of commerce, involving trade of goods or services with no money involved. And in this area of northern Spain, networks such as Rastru have developed that allow users to go online to match offers and needs, in a digital twist on an ancient tradition.

The system adopted by Rastru - which stands for Asturian network of barter communities - equates one trade-point known as a "copin" to one euro. It enables users to barter directly, or rack up the digital currency to get goods and services from others in the community. To attract business, users can also deal in a mix of euros and points.

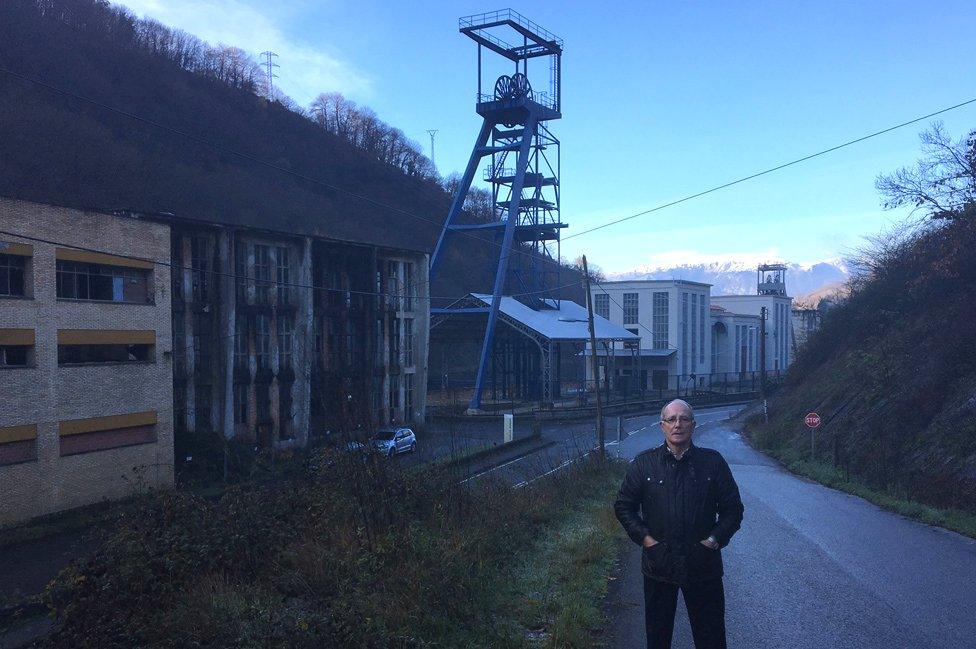

Asturias miners saw the pits close, leaving a tough legacy for their children

Asturias is littered with relics of its coal-mining heyday

"Barter means you can leave the bureaucracy alone, and that people who wouldn't otherwise have access to money have a way of surviving in the countryside," says Sergio Palacio Martin, who helped found the initiative and is also the son of a miner.

"The first stories that appeared about what's happening said we were all hippies. Now they're calling us entrepreneurs."

Across Asturias there are 78 municipalities, divided into nodes, he explains. Each one works autonomously. Since it started four years ago, nearly 1,500 users have shifted €350,000 (£300,000; $375,000) of produce between them.

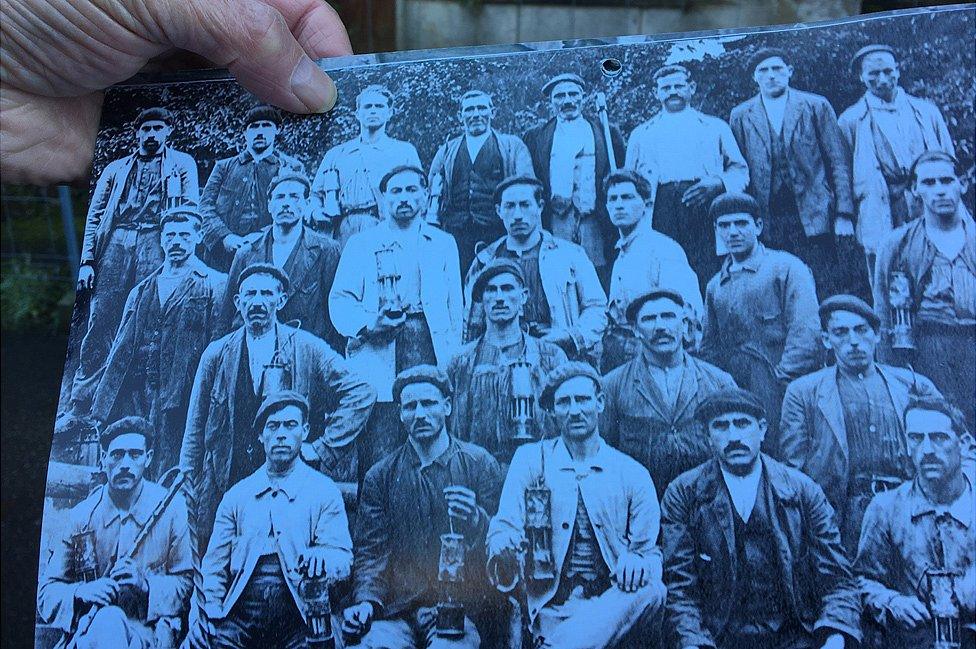

An old photo of Asturias miners: Coal was an integral part of everyday life

Return to the mountains

Until the mid-19th Century, most people from Asturias lived in smallholdings similar to that of Javi Fernandez. As coal and steel mining took hold, rural areas were abandoned and the central cities and industrial centres became overpopulated.

But Mr Fernandez says that has all changed and speaks of a big movement. "People from Asturias are returning to the mountains. They are having to learn about their rural environment, because there's nothing else for them, there's no work."

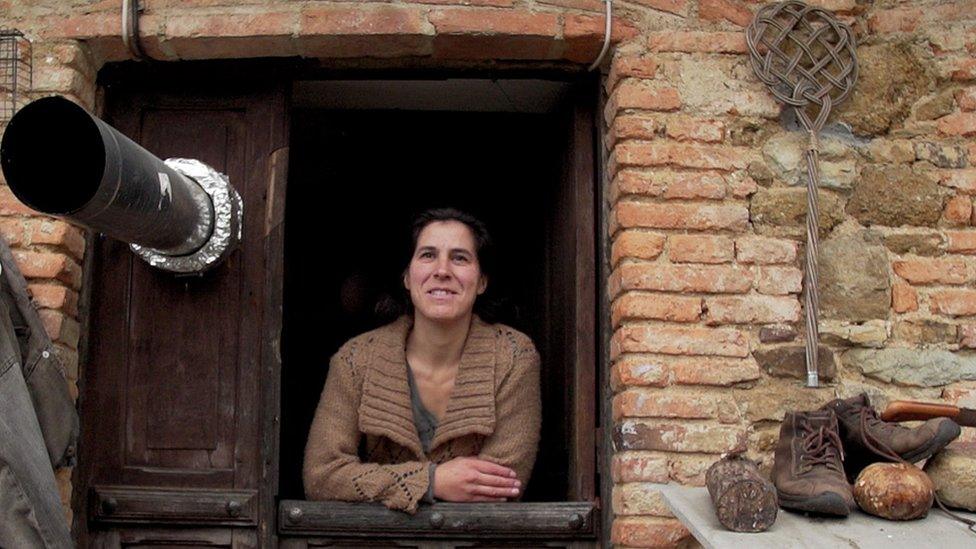

Violeta is happy that local people are returning to their rural roots

Further up the mountain, Violeta cuts pumpkins and turnips for a stew she's making for her kids. "It's not really new, this movement to the countryside," she says. "People were already rural, but then they moved to the city. Now a generation's moving back. It's just another episode; a return to their roots."

And there are opportunities here too. Asturias boasts 200,000 hectares of virgin, chestnut forest - Europe's biggest, says Javi. For now, the chestnuts drop to the ground and are eaten by wild boars.

The mild climate and rich soil are good for farming. "We have all we need here," says Violeta. "We came to make a future for ourselves, because in the city the future's dark and there are no possibilities. Here the possibilities are endless. There's forest, there's water, there's sun. We have what we want. "

The bartering activity is modest, and will not provide a lasting solution to these young people's problems. But it is a start and offers a chance to navigate a period of uncertainty and industrial decline.

- Published3 September 2014

- Published19 June 2012