Where will the EU's real centre be after Brexit?

- Published

Kevin Connolly visits the current centre of the EU and its future, post-Brexit location

These are troubled times for the leaders of the European Union.

Its leaders are beset with a whole series of issues that bubble away menacingly, even if they only occasionally come to the boil - like the Greek debt crisis.

And more ominously still, from their point of view, an organisation which has been in a state of constant expansion since its foundation in the 1950s is suddenly about to experience a bout of contraction.

It's true that Brexit does not mark the first occasion on which the EU has shrunk. It happened in 1962 when Algeria, which briefly became part of France in the panicky and violent end to the colonial period, gained independence.

And in 1985 the Autonomous Danish Territory of Greenland followed it out through the door of what was then the European Economic Community (EEC).

But neither of those events delivered the seismic shock to the system that Brexit will bring. The UK's withdrawal process is expected to start next month.

Its impact will be felt at all sorts of levels, from the economic and political to the diplomatic, legal and even sporting.

What is less obvious, perhaps, is that Brexit will have a geographical effect too. One German village is about to lose its status as the geographical centre of the EU and another is about to acquire it.

Hunt for centre

Calculating the centre of Europe - not the EU - can be done by taking into account the entire landmass of the continent. But even then the measurement is not straightforward. Is Belarus really part of Europe for these purposes? And what about European Russia or western Turkey?

Centre of the EU: Besancon in the 1950s, then Westerngrund and - after Brexit - Gadheim

Then there's the matter of outlying islands and overseas territories. You can skew the result quite a bit by including parts of France including Tahiti, Reunion and French Guiana.

So the location of the continental mid-point depends on what rules you adopt.

Every cartographer in history has faced similar issues.

In 1775 the Polish astronomer-royal, Szymon Sobiekrajski, calculated that the mid-point of the continent was in a town called Suchowola near Bialystok, in the north-east of modern Poland. It may be a coincidence, but he managed to place the centre inside the kingdom that paid his wages, by excluding the islands of Europe.

Years later the French National Geographical Institute (IGN) added in more of those territories and relocated the middle to a point near Purnuskes in Lithuania, where a proud government has erected a monument to mark the fact.

Calculating the centre of the EU of course includes similar geographical complexities. You have to remove geographically awkward countries like Switzerland, which are not part of the EU, for example - and then throw in a bit of politics too.

Viroinval, in Belgium, was the EU's centre from 1995 until its 2004 expansion, and has a monument to mark it

The EU has expanded in a series of steps since it - in the form of the EEC - was created by the Treaty of Rome in 1957. (It seems reasonable to ignore the previous iron and steel community for these purposes, since this is complicated enough already.)

The French IGN has recast the calculation each time the union has changed, providing a kind of dynamic map of how the EU has evolved over time.

In the 1950s for example - when the union was a community of six countries and the eastern provinces of the still disunited Germany were excluded - the centre was calculated to sit near the Franco-Swiss border in the Doubs valley, outside the ancient city of Besancon.

As the EU expanded the notional centre began to move - first to the Auvergne in France and then gradually, in the wave of eastward expansion that followed the end of the Cold War, into Germany.

From 2004-2007 the centre of the EU (which then had 25 members) was in Kleinmaischeid in Germany

The last time it moved of course was when Croatia joined the union in 2013. Because that's not a huge landmass the effect was merely to nudge the mid-point a little way to the south-east, to the point where it now sits in the Bavarian village of Westerngrund.

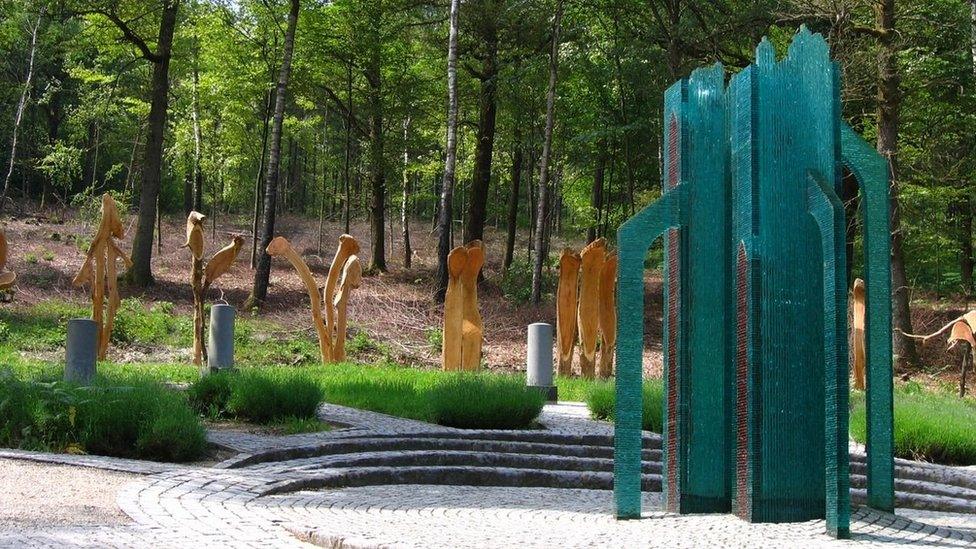

The local people are delighted - they have built a little park with flags around it in a field just outside the village. And there is a kind of flask which contains a little soil from each member state, topped off with a bit of earth from Croatia.

In a modest way it has become a bit of a tourist attraction too - the last people who signed the visitor's book before me had written a lengthy message in Chinese.

Rural Westerngrund is proud to be the current centre of the EU - a far cry from Brussels

Tranquil heart

Like many Europeans the people we met in Westerngrund were saddened and mystified by Brexit, which they saw as a perverse attempt by one of the EU's larger powers to decouple itself from one of history's prime motors of peace and prosperity.

Once the UK has left of course the centre point of Europe will move again, a little way down the road to the village of Gadheim.

It is a quiet and essentially rural place, and for the moment at least there is nothing there to show that its people are preparing to mark their new status, or to welcome a sudden influx of tourists.

They have a little time to prepare. Even the first formal stage of Brexit won't be completed for two years and no one knows how long a negotiation will follow in whatever trade talks are to come.

And Gadheim might hold on to its status for quite a while. The centre point will not move again until someone else leaves or joins the EU. And after the shock and complexity of Brexit there's no sign that anyone else is heading for the exit door.

Nor is there much indication that potential future members like Ukraine, Bosnia or Turkey are getting close to entering.

If the taxpayers of Gadheim do decide to stump up for a new garden with flags and a visitor book then at least they might get a few years' use out of it.

- Published14 February 2017

- Published30 December 2020