Europe's future: Small steps rather than big dreams?

- Published

How do you celebrate in a time of acute anxiety, how do you party in the midst of a family divorce and how do you mark an anniversary when allies predict your demise?

Europe does not know but less than three weeks' time, on 25 March, its leaders will gather in the Piazza del Campidoglio, the square designed by Michelangelo to try to answer those questions.

They will be in Rome to mark the 60th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Rome that gave birth to the European Economic Community, the forerunner of the EU.

It was the Treaty of Rome that set out the Union's goal of "ever closer union among the peoples of Europe".

There is much excited talk that "Rome must also be the start of a new chapter" and an occasion to "relaunch the European Project".

Brexit: All you need to know about the UK leaving the EU

What might a post-Brexit EU look like?

After Brexit: Jean-Claude Juncker sets five paths for EU's future

Where will the EU's real centre be after Brexit?

Ode to Joy, the so-called anthem of Europe, will no doubt be played and there will be a March for Europe through the Roman streets.

Theresa May joined EU leaders in Valletta in February, but will skip the celebrations in Rome

It will be intended to demonstrate that the European idea has lost none of its appeal.

But such are the insecurities surrounding the occasion that the Italians fretted that Prime Minister Theresa May might just trigger Article 50 during the final week of March.

They made it clear that serving divorce papers at such a moment would be deemed almost a hostile act.

Crisis of faith?

To digress for a moment: The Treaty and the talks that led up to its signing only underline Britain's fractured relationship with Europe.

Whitehall sent a civil servant to observe these early steps towards a Common Market and it has not been forgotten how he dismissed the whole enterprise.

"The future treaty which you are discussing," he told the diplomats, "has no chance of being agreed.

"If it was agreed, it would have no chance of being ratified. And if it were ratified, it would have no chance of being applied. And if it was applied, it would be totally unacceptable to Britain."

With that he bid the Europeans "Au revoir et bonne chance" and headed home.

Returning to the present dilemma, on one level it is easy to celebrate what most Europeans agree is "the most successful peace project of our time".

But the crisis of faith is inescapable. It even seeped into a white paper setting out the options for the future., external

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker set out five possible futures

The European Commission, normally a cheerleader for the Union, warned it was seen as "either too distant or too interfering in their day-to-day lives".

The white paper is an exercise in timidity. It sets out five different options: muddling through, scaling back to only a single market, doing less but more efficiently, allowing for different levels of integration and deepening the union.

The President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, would not even signal his preference.

"Ever closer union" did not get a mention. The frustration of one party in the European Parliament boiled over. Europe's ambitions, it said, were being reined in out of fear of alienating voters in Europe's election season.

The rise of the incrementalists?

The European voice is uncertain because the project is at a crossroads.

The French presidential elections pose an existential threat to the Union. Marine Le Pen is running against what she calls the "anti-democratic monster" of the EU.

How right-wing politicians Geert Wilders and Marine Le Pen fare in national elections will be key

She is not expected to win the crucial second round but some recent polls have worried the bond markets and Europe's leaders.

Europe's political establishment has fallen in behind the centre-left candidate Emmanuel Macron who is pro-European, pro the Franco-German relationship and pro-globalisation.

If he wins, Europe's leaders will breathe more easily. Before the French elections the Dutch go to the polls. The anti-EU/anti-immigration candidate is Geert Wilders. He might top the poll but will not be in government.

If the European Union emerges unscathed from its election year, it will still face fundamental questions about its future. The expectation in Brussels is that the Brexit negotiations will be messy and acrimonious.

To many MEPs, "more Europe" is destiny. Closer integration is in the Commission's DNA, but few believe this is the time to further reduce national sovereignty.

A majority of European leaders are probably incrementalists. They believe in expanding the single market where it is possible. They incline towards setting up a European Treasury with common taxation.

But there are limits. Any move towards common debt, a transfer union, would be resisted by Germany.

Angela Merkel has faced criticism for her immigration policies from many German voters

For others, including Angela Merkel, the priority is securing external borders and demonstrating that Europe can defend itself. It is not only German politicians but the Commission who are urging increased deportations of illegal migrants.

Europe is already a multi-speed Europe, but Eastern and Central European countries are wary of becoming second-class Europeans.

Hard-headed approach?

The polls offer some reassuring news for Europe's leaders.

The four freedoms, including freedom of movement, remain popular, as does the Erasmus student exchange programme.

Even in a country like Greece, a majority remain in favour of staying in the euro.

So the course of least resistance is to once again muddle through. It is not the time to rekindle the dreams of Schuman and Monet.

Until recently Europe's leaders had reassured themselves that globalisation would lead to a withering away of the nation state.

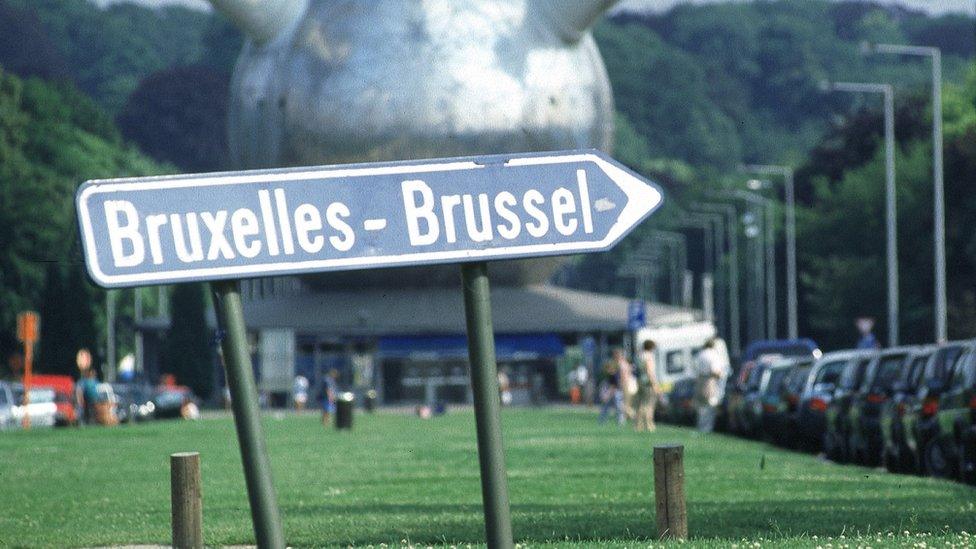

Brussels expects the Brexit negotiations to be difficult and acrimonious

The global economy with its supply chains and capital flows made supranational institutions more necessary. However the insecurity that comes with globalisation has left many voters clamouring for older identities.

In the past Europe's politicians often disguised their ambitions. Europe was built through the added layers of its institutions. It seemed to some that Europe was being created by stealth but it remains a top-down project.

In these turbulent times, as Europe debates its future, there is a more fundamental question.

On whose side are the politicians and leaders?

Is Europe about the promotion of an idea, a project and a dream, or is it about delivering security to restless citizens in the midst of dramatic change?

What we are beginning to see is a more hard-headed approach to issues like migration in the face of the rise of anti-establishment parties. It is not a question of stealing the clothes of populists, but Europe's leaders are having to adapt for their own credibility.

On 25 March, Europe will celebrate, but its future will be made of small steps rather than big dreams.

- Published30 December 2020

- Published4 March 2017

- Published1 March 2017

- Published22 February 2017