Turkey's Erdogan warns Dutch will pay price for dispute

- Published

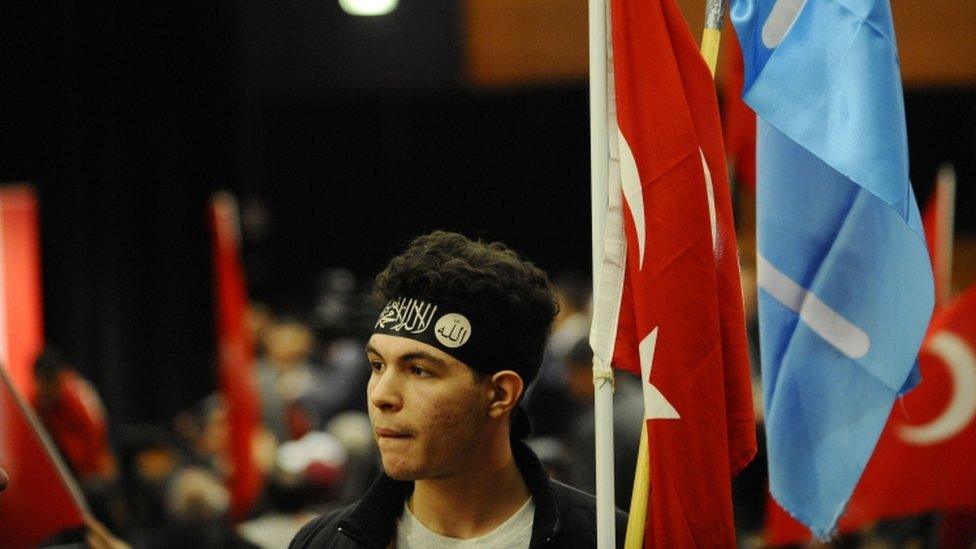

President Erdogan: "We will teach them international diplomacy"

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has warned the Netherlands it will "pay the price" for harming ties after two of his ministers were barred.

The two ministers were blocked from addressing Turkish voters in Rotterdam on Saturday, with one of them escorted to the German border.

The Dutch government said such rallies would stoke tensions days before the Netherlands' general election.

Turkey's ties with several EU countries have become strained over the rallies.

The rallies aim to increase support among Turks living in Europe who are eligible to vote in a referendum on expanding Turkish presidential powers.

Fatma Betul Sayan Kaya, Turkey's family minister, had arrived in Rotterdam by road on Saturday, but was denied entry to the consulate and taken to the German border by Dutch police.

Protesters gathered outside the Turkish consulate in Rotterdam on Saturday night

Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu tried to fly in but was refused entry.

'Capital of fascism'

Several EU countries have been drawn into the row over the rallies:

Mr Cavusoglu called the Netherlands the "capital of fascism" after he was refused entry

Mr Erdogan accused Germany of "Nazi practices" after similar rallies there were cancelled - words Chancellor Angela Merkel described as "unacceptable"

Denmark's Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen postponed, external a planned meeting with Turkey's prime minister, saying he was concerned that "democratic principles are under great pressure" in Turkey

Local French officials have allowed a Turkish rally in Metz, saying it does not pose a public order threat - while France's foreign ministry has urged Turkey to avoid provocations

Mr Erdogan accused countries in the West of "Islamophobia" and demanded international organisations impose sanctions on the Netherlands.

"I have said that I had thought that Nazism was over, but that I was wrong. Nazism is alive in the West," he said.

He thanked France for allowing Mr Cavusoglu to travel to Metz to address a rally.

A look at how tensions between Turkey and the Netherlands unfolded

The Netherlands' Prime Minister Mark Rutte has demanded Mr Erdogan apologise for likening the Dutch to "Nazi fascists".

"This country was bombed during the Second World War by Nazis. It's totally unacceptable to talk in this way."

Mr Erdogan's comments were "completely unacceptable", and the Netherlands would have to consider its response if Turkey continued on its current path, he added.

The Dutch government is facing a severe electoral challenge from the anti-Islam party of Geert Wilders in its election on Wednesday.

On Sunday a protester outside the Dutch consulate in Istanbul briefly replaced the Dutch flag with a Turkish one

Reports say the owner of a venue in the Swedish capital, Stockholm, has also cancelled a pro-Erdogan rally on Sunday that was to have been attended by Turkey's agriculture minister.

Sweden's foreign ministry said it was not involved in the decision and that the event could take place elsewhere.

What is the row about?

Turkey is holding a referendum on 16 April on whether to turn from a parliamentary to a presidential republic, more akin to the United States.

If successful, it would give sweeping new powers to the president, allowing him or her to appoint ministers, prepare the budget, choose the majority of senior judges and enact certain laws by decree.

President Erdogan is hoping to win sweeping new powers

What's more, the president alone would be able to announce a state of emergency and dismiss parliament.

There are 5.5 million Turks living outside the country, with 1.4 million eligible voters in Germany alone - and the Yes campaign is keen to get them on side.

So a number of rallies have been planned for countries with large numbers of eligible voters, including Germany, Austria and the Netherlands.

Why are countries trying to prevent the rallies?

Many of the countries, including Germany, have cited security concerns as the official reason.

A rally did go ahead in Metz in France on Sunday

Austrian Foreign Minister Sebastian Kurz said Mr Erdogan was not welcome to hold rallies as this could increase friction and hinder integration.

Many European nations have also expressed deep disquiet about Turkey's response to the July coup attempt and the country's perceived slide towards authoritarianism under President Erdogan.

Germany in particular has been critical of the mass arrests and purges that followed - with nearly 100,000 civil servants removed from their posts.

- Published12 March 2017

- Published11 March 2017

- Published27 February 2017

- Published16 April 2017