Information warfare: Is Russia really interfering in European states?

- Published

Russian hackers have been blamed for hacking the US Democratic National Committee and the German parliament

Russia has been accused of trying to interfere in the US presidential election, through hacked Democrat emails and social media.

And in a big year of European elections, political leaders in France, Germany and elsewhere are looking over their shoulders too.

Across the continent the hand of the Russian state has been perceived in an array of cyber attacks on government and state institutions, in the phenomenon of "fake news" and disinformation, and in the targeted funding of opposition groups.

So how real is the threat and what form does it take? And is an explanation to be found in the words of Russia's chief of the general staff, Gen Valery Gerasimov, who wrote in a military newspaper in 2013 that "the very rules of war have changed"?

What's so new about information warfare?

Attempting to control information has long been part of the weaponry of many powerful states.

But Russia's concerted effort to cultivate techniques of information warfare and non-military intervention over recent years is something new, says Keir Giles of the Conflict Studies Research Centre.

"At various stages in the first and second Chechen wars, the war with Georgia in 2008, Russia found it was not able to influence global opinion or the opinion of its adversaries at an operational or strategic level, and made significant changes to its information warfare apparatus as a result," he says.

Russia learned lessons from its 2008 campaign in Georgia

"In the Georgia war, they found that to influence world public opinion and to properly exploit the connectivity of the internet they needed to start a massive recruitment campaign to bring in linguists, journalists, anybody who could talk directly to populations in foreign countries en masse".

What techniques are available?

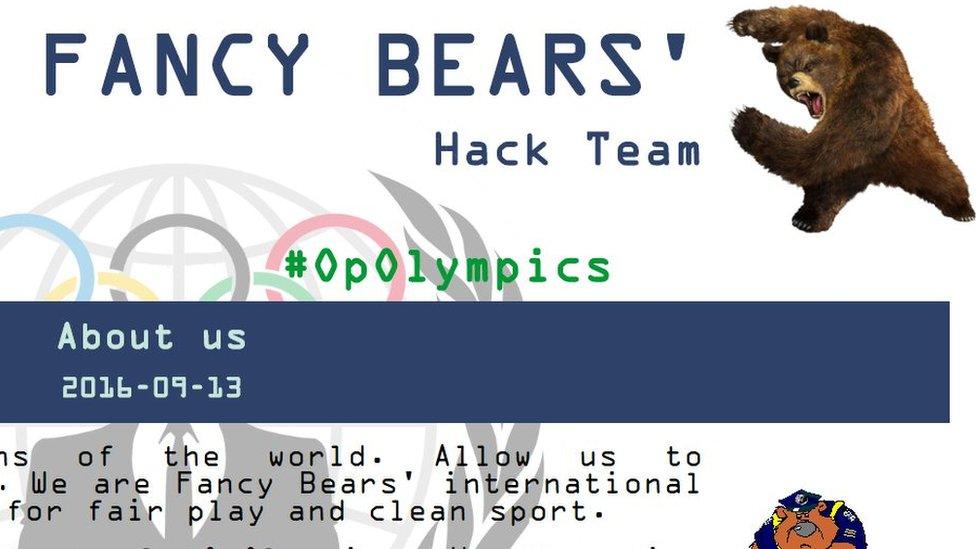

HACKING

Numerous cyber attacks in Europe have been blamed on Russian-linked groups - many of them spectacular.

In 2015 France's TV5Monde broadcaster was taken off air and its systems nearly entirely destroyed.

The same year Russia's APT28 hacking group was accused of a massive data hack of deputies in Germany's lower house of parliament involving the loss of 16 gigabytes of data. Germany's head of domestic intelligence has since spoken of a "hybrid" Russian threat to the September 2017 elections in which Angela Merkel is seeking a fourth term in office.

TV5Monde was taken off air in April 2015

Another cyber attack, on Bulgaria in October 2016, was described by its president as the heaviest and most intense to be conducted in south-eastern Europe.

These types of attack date back 10 years, when Estonia, a cyber pioneer and former Soviet state, was hit by a massive denial-of-service attack, external rendering websites inaccessible with a barrage of requests.

The potential power of attacking a country's internet infrastructure suddenly became clear, with an Estonian defence spokesman comparing the attacks to those launched against the US on 11 September 2001, external.

Hacking is not just an issue in cyber-space, it can have enormous consequences far beyond. An attack on a Ukrainian power plant in 2015 led to days of blackout.

Read more: Bears with keyboards - Russian hackers snoop on West

BOOSTING OPPOSITION PARTIES

Senior Russian political figures have long cultivated relationships with nationalist and often anti-EU parties in Europe.

President Putin denied trying to influence events in other countries' elections

In France, Marine Le Pen's far-right National Front received a €9m loan from a Russian bank in 2014 (then £7m; $11m). On 24 March, with the French election only a month away and a chance of victory in the race, she met President Putin during a trip to Moscow.

In February, the leader of right-wing nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD), Frauke Petry, held talks in Moscow with MPs close to President Putin and with Russian ultranationalists.

And in Austria, the far-right Freedom Party of Austria denied claims it had received money from Moscow, external after signing a co-operation agreement with Mr Putin's United Russia party.

Apparently it is not just the right. In France and Germany, leading far-left groups also have key links to the Russian state, according to this study by the Atlantic Council, external.

FAKE NEWS AND DISINFORMATION

There is nothing new about disinformation - intentionally spreading false facts.

Now there is "fake news" too - false or misleading reporting often originating from little-known fringe websites that claim they are providing an alternative to the "lying" mainstream media.

The US presidential election was notoriously hit by it and many European countries have been too.

When Russian forces invaded Crimea in 2014, the leaders that took over from Ukraine's deposed leader were painted as fascists, justifying their intervention. The story contained enough of a kernel of truth to be persuasive. The leadership was neither a "fascist junta" nor "completely fascist-free", as the BBC's David Stern said at the time.

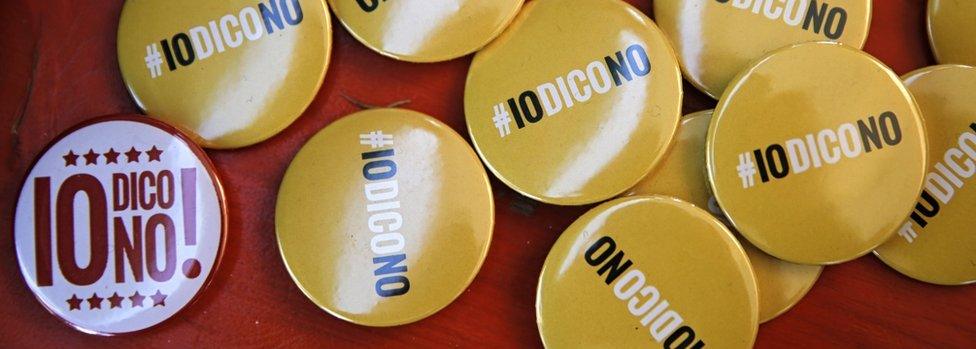

Weeks before an Italian referendum that brought down Prime Minister Matteo Renzi in December 2016, Kremlin-funded TV Russia Today broadcast a rally on Facebook Live from Rome's Piazza del Populo.

"Protests against Italian PM hit Rome," it announced to hundreds of thousands of viewers. In reality, it was a rally backing Mr Renzi.

Did disinformation help the No vote win in Italy's referendum?

In Germany, a 13-year-old girl, "Lisa", told police she had been raped by people of "Mediterranean appearance" in January 2016. Russian state TV seized on the story, reporting it intensively and triggering anti-migrant protests against Chancellor Angela Merkel.

It was later established the story was false, and Berlin hit out at Moscow for making political capital out of the case.

Pressing Moscow's case are Russian-backed news organisations such as RT and Sputnik. and, on social media, an army of "internet trolls".

The EU is so worried that it has established a unit of experts, external explicitly tasked with tackling "Russia's ongoing disinformation campaigns".

Can we be sure Russia is behind all this?

Russia denies it. President Vladimir Putin says US intelligence claims of interference are absurd and irresponsible. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has even accused the CIA of masquerading as Russian hackers.

But, according to Keir Giles, Russia "is becoming less and less interested in covering its tracks". Its interference in the US election was more or less overt, he argues, and it was happy to permit dozens of Western journalists to visit a notorious St Petersburg troll farm.

That is, he says, "partly because of a sense of urgency that the next conflict is coming".

An EU official told the BBC that disinformation campaigns were not always top-down. "It's not like every single piece of it is orchestrated by the Kremlin," the official said.

"It's about creating this ecosystem that works in significant parts almost independently", with actors working for financial motives such as clicks or funding from Russian organisations.

Thousands of Russian-speakers in Germany took to the streets in response to false Russian TV reports of a rape

In the case of the "Lisa" rape case in Germany, the story originated on a small blog, not in Moscow.

But it is telling, says the official, that journalists behind the propaganda are decorated with state medals - including 300 journalists covering Russia's annexation of Crimea, external and 60 pushing a pro-Kremlin narrative on Syria.

What is Russia trying to achieve?

For some critics, the answer is simply power.

President Putin and his allies have created "an image of the external enemy from the West… this demand was dormant, Putin awakened it," says Andrei Kolesnikov of the Carnegie Moscow Center.

"His goal is to be a world leader, but on his own terms."

Others are more nuanced.

For Maria Lipman, external, while anti-Western sentiment in Russia has been nurtured by the state, the mindset of a fortress under siege "is not necessarily unfounded". She points to the sanctions imposed by the US and EU "couched in the language of punishing Russia to hurt its economy".

Many chart the decline of Russian relations with Europe from Ukraine's Orange Revolution in 2004-5, seen in Moscow as "regime change", through Russia's gas wars with Ukraine, its 2008 conflict with Georgia to the crisis and conflict in Ukraine. It was the 2014 annexation of Crimea that led to the sanctions.

For Gonzalo Pozo Martin of Stockholm University, the pain of those sanctions has been felt most intensely in Russia and has coincided with falling oil prices.

He argues that Russia's "cosying up" to the hard right in Europe is a form of leverage over the sanctions and deadlock in eastern Ukraine. But he also believes the Kremlin is investing long term in a more amenable, less Atlanticist EU.

Not only would that boost Russian influence, it "might afford Russia a freer hand over its former-Soviet neighbours", he suggests.

- Published13 May 2016

- Published11 February 2017

- Published3 February 2017

- Published12 November 2015